|

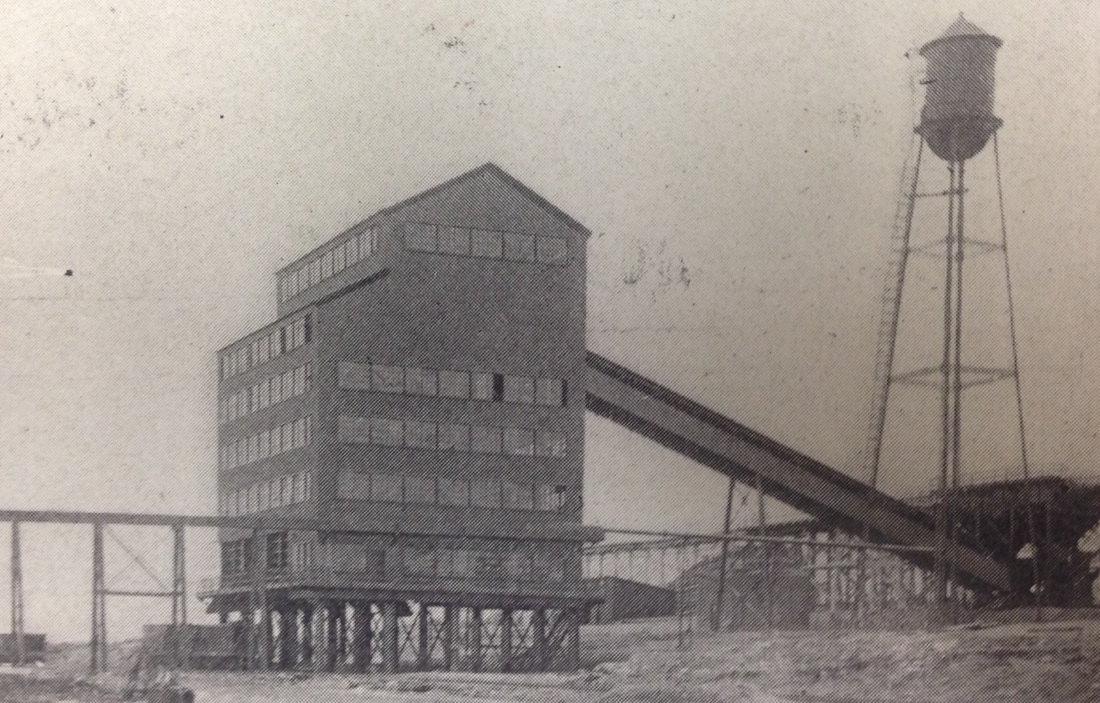

"But the hematite in the tailings seemed possessed of a wanderlust." (EMJ, Vol. 97, No. 05, Jan 31, 1914, pp. 293) Historic mining landscapes can be read as palimpsests, featuring the the ongoing conversation between an evolving technological system and its changing environment. Sometimes these conversations are easy to follow, but more often than not, they tend to resemble the creative genius of Sokal - convoluted, cacophonous, and confusing. When reading mining landscapes it is often difficult to remember that many of the mining features that may seem ubiquitous today were not always there. Instead, these features are products of an evolving technological system - artifacts of the conversation between technology and nature. In the historic Mesabi iron range, tailings ponds and tailings basins are mining features evident throughout the range's 100 mile stretch, running from Grand Rapids to Babbitt, but less than a century ago, these mining features were absent, as the concentrating plants that created them were still only nascent features on the landscape.

This brings us to a question I continue to dwell on: What impact did the sudden visibility of tailings in the Mesabi Range have on public perceptions regarding iron mining, ore processing, and the environment? Part of the answer to this question is found near Nashwauk, MN and the O'Brien Lake ecosystem, where a handful of Hibbing "publicans" saw the shoreline of their summer retreats turn red during the summer of 1912.

1 Comment

|

AuthorJohn Baeten holds a PhD in Industrial Heritage and Archaeology from Michigan Technological University. His research aims to contextualize the environmental legacies of industrialization as meaningful cultural heritage. Archives

May 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed