|

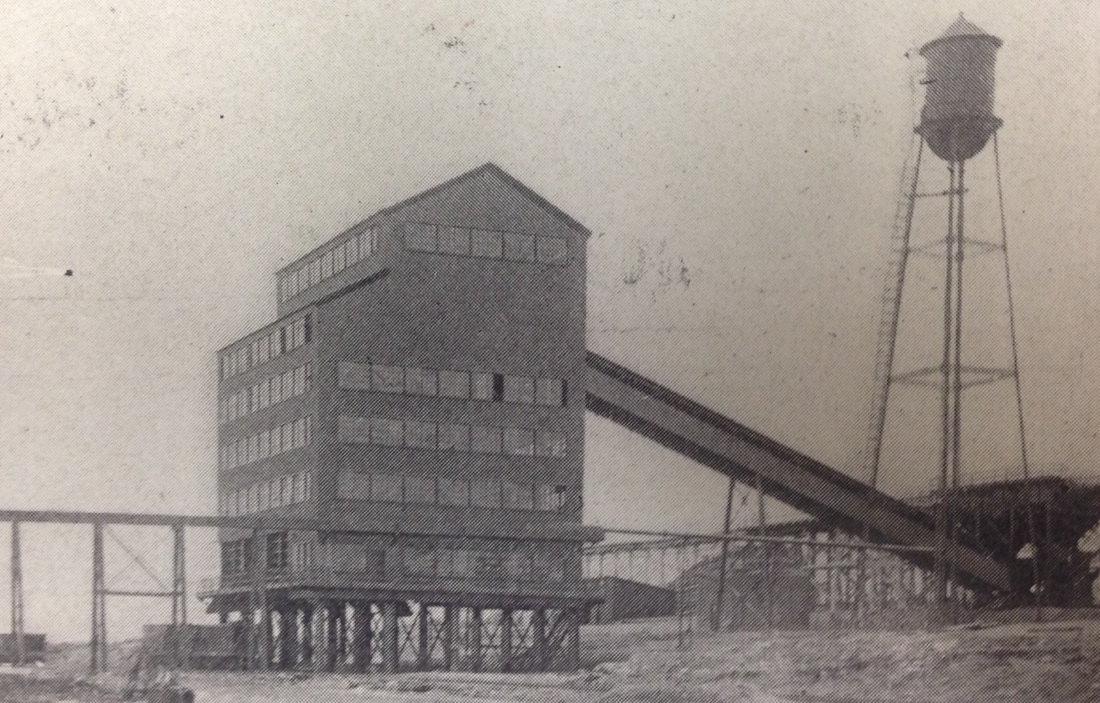

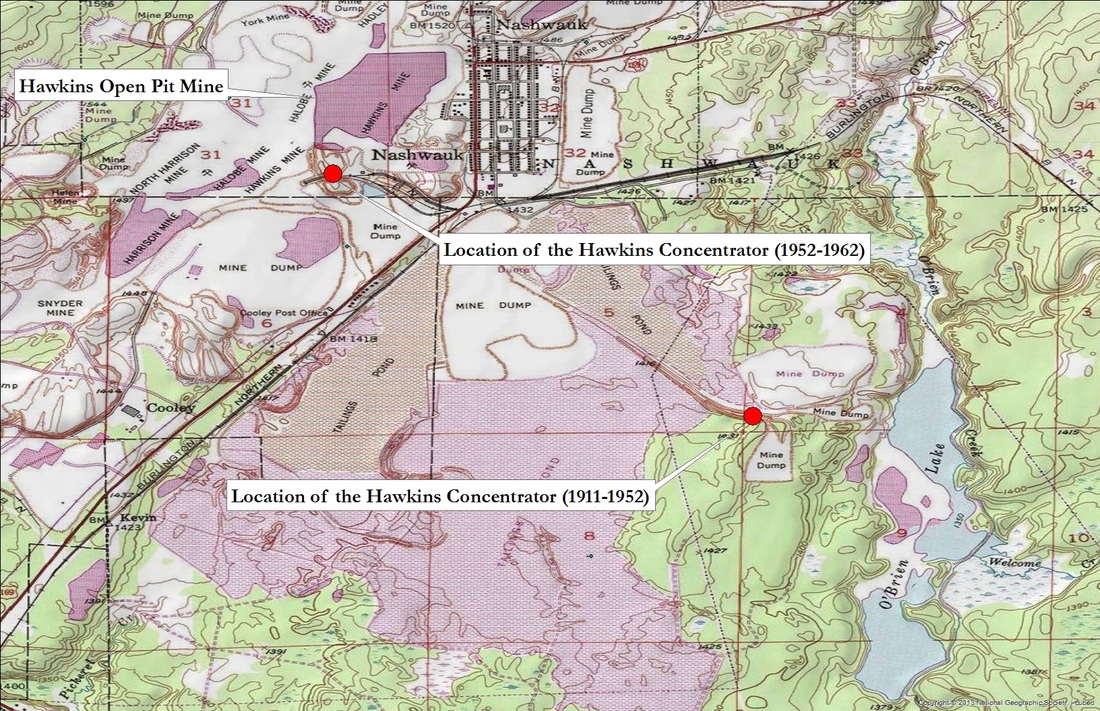

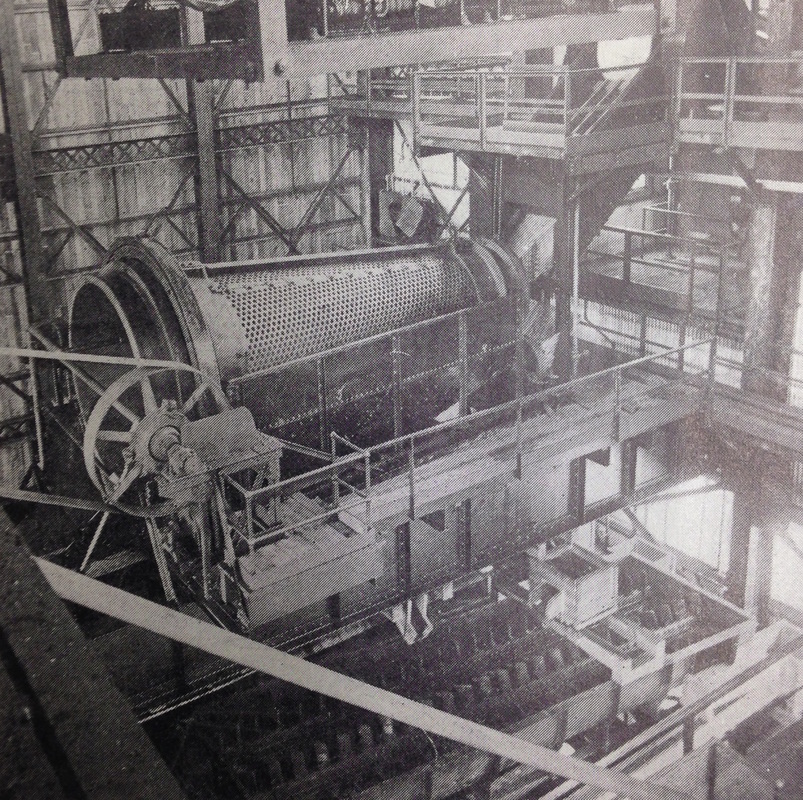

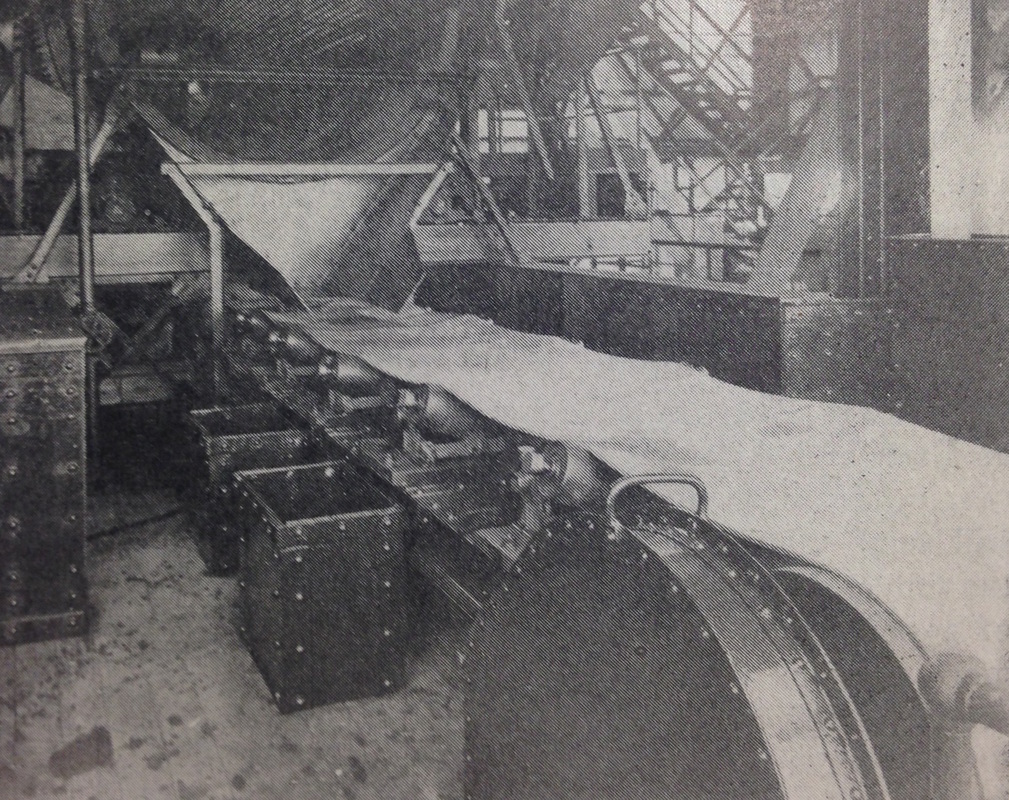

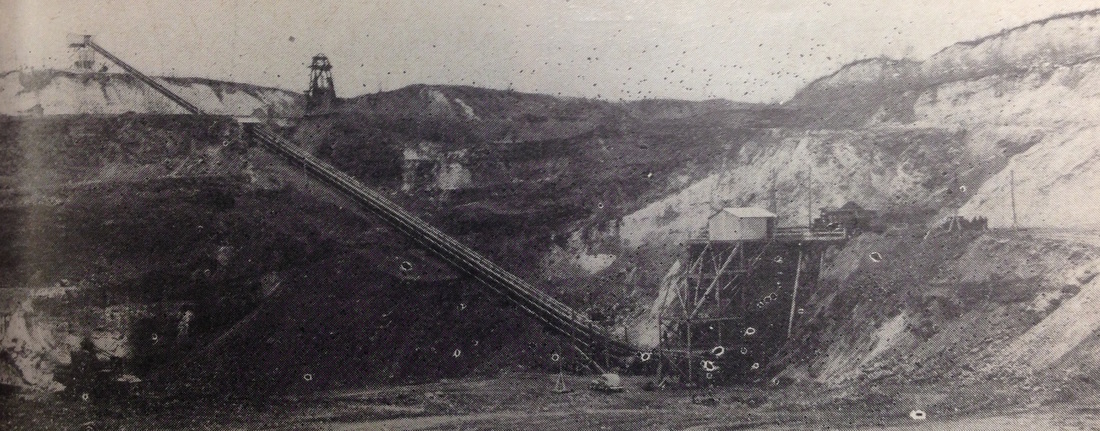

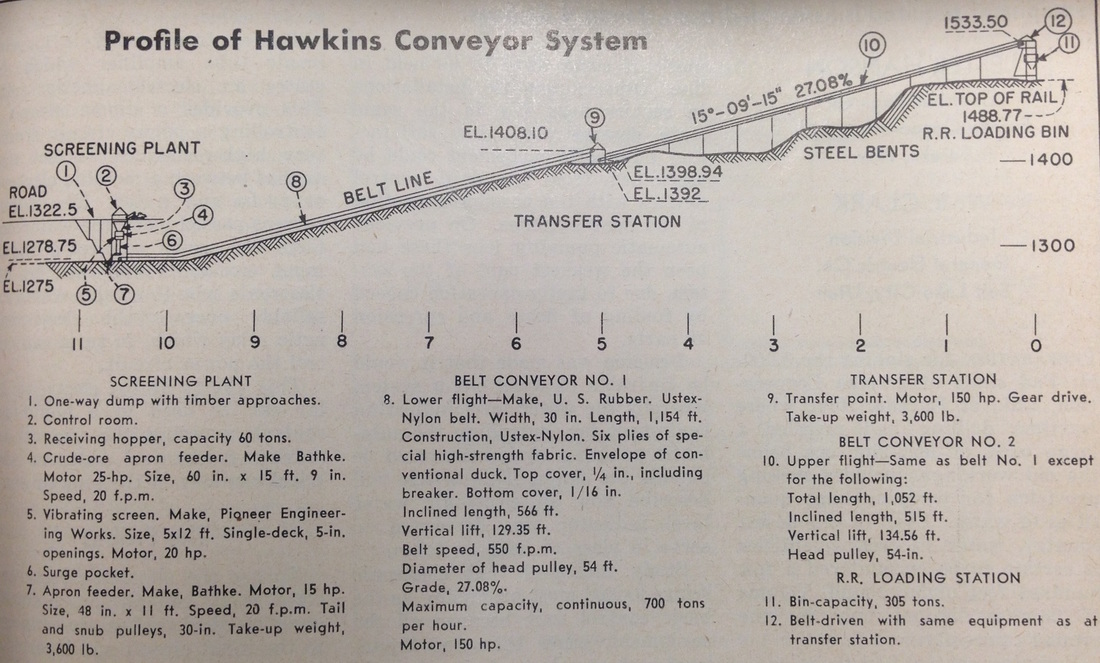

"But the hematite in the tailings seemed possessed of a wanderlust." (EMJ, Vol. 97, No. 05, Jan 31, 1914, pp. 293) Historic mining landscapes can be read as palimpsests, featuring the the ongoing conversation between an evolving technological system and its changing environment. Sometimes these conversations are easy to follow, but more often than not, they tend to resemble the creative genius of Sokal - convoluted, cacophonous, and confusing. When reading mining landscapes it is often difficult to remember that many of the mining features that may seem ubiquitous today were not always there. Instead, these features are products of an evolving technological system - artifacts of the conversation between technology and nature. In the historic Mesabi iron range, tailings ponds and tailings basins are mining features evident throughout the range's 100 mile stretch, running from Grand Rapids to Babbitt, but less than a century ago, these mining features were absent, as the concentrating plants that created them were still only nascent features on the landscape. This brings us to a question I continue to dwell on: What impact did the sudden visibility of tailings in the Mesabi Range have on public perceptions regarding iron mining, ore processing, and the environment? Part of the answer to this question is found near Nashwauk, MN and the O'Brien Lake ecosystem, where a handful of Hibbing "publicans" saw the shoreline of their summer retreats turn red during the summer of 1912. Nashwauk, Minnesota is located in Itasca County, roughly 20 miles west of Hibbing, within the western Mesabi Iron Range. Nashwauk was home to the first successful mine in the Western Mesabi, the Hawkins, which began producing merchantable ore in 1901. Originally owned by the International Harvester Co. and operated by Wisconsin Steel, the Hawkins mine helped the village of Nashwauk expand and develop from a small timbering community of around 200, to a functioning city of over 2,000 in a period of only a few years. "The Nashwauk plant of the Wisconsin Steel Co., as a solution to its difficulties with riparian owners on Swan Lake, is constructing a channel to divert the water flowing into O’Brien Lake, so to leave most its area isolated and available for tailing dumping, if desired.” (L. O. Kellogg, “Lake Superior Iron Ranges”, in EMJ, Vol. 97, 10 Jan. 1911, p. 84). The Hawkins washing plant was the second low-grade concentrator built on the Mesabi Range, erected 2 years after Oliver Iron Mining Company’s concentrator at Trout Lake went into service. Built by the International Harvester Co., and operated by the Wisconsin Steel Co., the Hawkins washing plant was designed to treat an average of 5,000 tons of washable ore per day. During its first year of operation the Hawkins concentrator was receiving between 50- 60 cars of ore per day from its namesake mine, resulting in the concentration of around 500,000 tons of ore for the 1912 season. (Mining & Engineering World, 2 November 1912, pp. 819). Although it wasn't the first constructed (see the Trout Lake Concentrator), didn't have the largest capacity, nor was it the longest running beneficiation plant in the Mesabi, the Hawkins washing plant was the first processing plant to create public outcry over its production and disposal of tailings in the Western Mesabi. "The tailing flows out of the mill through an elevated launder which discharges onto an area of low land where the solid tailing accumulates, and the water drains back into the small lake near which the mill is built." ("Iron Ore Concentration in Minnesota", in Metallurgical and Chemical Engineering, Vol. 10, No. 11, 1912, pp. 719). One of the joys of research are those serendipitous moments when you locate a gem of information you didn't know you were even looking for. Case in point with the Hawkins concentrator. I began skimming through old trade journals from 1910-1914, looking for information regarding the plant's technical make-up, but instead stumbled upon a handful of entries regarding lawsuits and public reaction to the Hawkins' production and disposal of tailings. Entry 1: During this time period (1913) the construction of tailings basins was unheard of in the Mesabi Range. Dumping of tailings in water bodies was common place, and any negative effects felt by the public were simply written off as meager impacts from living with the many benefits of the industrial machine: “Enjoinment was refused by both the state of Minnesota and the federal court at Duluth when an effort was made to get out an injunction to prevent the Wisconsin Steel Co. from discoloring the waters of Swan Lake, on the Mesabi Range, by the washing of its ores. A resident of the vicinity applied for a restraining order. The state’s attorney general took the position that the state would not feel justified in injuring so important an industry for so slight a cause, whereupon appeal was made to the Federal Judge Page Morris. Attorney C. O. Baldwin, opposing the petition, declared that the principle of preventing mining companies from washing their ores because waters of comparatively little use were affected would seriously embarrass the mining of 100,000,000 tons in the western part of the Mesabi, so Judge Morris refused to issue the order.” (Editiorial Correspondence, EMJ, Vol. 96, No. 17, 25, Oct. 1913, pp. 806). Entry 2: Here, you can ascertain how the mining industry, and civil servants felt about complaints regarding the mining industry. Environmental concerns were not taken seriously, and questions of environmental justice were viewed as fallacious. "The Wisconsin Steel Co. built itself a fine new concentrator near O'Brien Lake on the Mesabi range. Although only one unit, it will wash 8000 tons of ore per day. The tailings are discharged into a pond and the overflow enters the lake. The company has carefully sewed things up so that no complaints would come from owners of the shore line; and it was expected that little material would get to the lake anyhow. But the hematite in the tailings seemed possessed of a wanderlust. Not only did it flow into O'Brien Lake, put proceeded on down to Swan Lake, it is said, into which O'Brien Lake drains. Now the red coloring power of a little hematite slime is equaled only by the green-staining ability of oxidized copper. Swan Lake, it is stated, soon began to assume the color of that slow poison known as "Dago Red". Certain publicans of Hibbing had summer cottages on Swan Lake and these publicans declared they were dismayed and disgusted by the discoloration of their formerly pellucid water. Just why publicans should have been displeased at such as color transformation, is not clear; perhaps they found it tantalizing; possibly they saw a chance for profit. At all events, they or their lawyers are said to have sued the Wisconsin Steel Co. - who shall say in such cases whether lawyer of client be the real plaintiff? - alleging infinite damage to their valuable property holdings. Somehow to the company this action bore the earmarks of a holdup; nor did it care to be held up." ("By the Way", in the Engineering and Mining Journal, Vol. 97, No. 5, 31 January 1914, pp. 293-294). The only real change in the concentrating process as compared to the Trout Lake concentrator, which the Hawkins was modeled after, was the commission of tables for fines. This meant that the Hawkins plant's required less water for washing than the Trout Lake concentrator, running on an initial consumption rate of around 1200 gallons of water per minute. Entry 3: The company response resulted in the the safe keeping of Swan Lake, but also the creation of a stagnant pond at O'Brien. "It seems that O'Brien Lake is fed by two small streams, both on one side, with the outlet to Swan Lake at one end. So the company put a steam shovel to work and is digging, ditching and diking in such a way that the bays on the side of the lake where the streams enter will be diked off, the points cut through and at the end a large ditch excavated to enter the outlet stream some way below the lake. Thus the clear entering water will be confined to a new channel and conveyed to Swan Lake safe from contamination, and most of O'Brien Lake shut off as a stagnant pond." ("By the Way", in the Engineering and Mining Journal, Vol. 97, No. 5, 31 January 1914, pp. 294). The migration of tailings that moved from the launders of the Hawkins' concentrator, through O'Brien Lake, into O'Brien Creek, and eventually settling on the banks of Swan Lake resulted in one of the first instances of the public attempting to use legal avenues to protect their environment. This action forced the International Harvester Co. to construct the first tailings remediation structure in the Mesabi Range. This tailings dike that was constructed, was put in place to alter the route of the migrating mine waste, a strategy the company pursued to likely lessen the chance of future lawsuits and public ill will, and to thwart future legal intervention into the mining company's day-to-day activities. However, this landscape alteration had a lasting affect on the O'Brien ecosystem, as it plugged up one of O'Brien Lake's main arteries. During the 1952 season the original Hawkins concentrator was shut down and a new facility was opened adjacent to the Hawkins pit. I've yet to discover if old plant was simply moved to the new location, or if an entirely new facility was constructed. It does look like that in 1953, additions were made to new plant, including an additional sink-and-float Heavy Media section, as well as a 2-unit cyclone plant. (EMJ, Vol. 154, No. 7, July 1953, pp. 202). -Updated- Entry #4: During the late 1950s the impending exhaustion of the Hawkins Mine became apparent to Cleveland Cliffs, and attention was placed on the nearly 8-million tons of tailings residing within O'Brien Lake. As the company began to draw up plans to reclaim and retreat these tailings, questions of ownership were challenged by the State in court: "The district court, in an action brought against the International Harvester Co., Cleveland Cliffs Iron Co., and others, by the state of Minnesota, held that iron ore tailings deposited in O'Brien Lake near Nashwauk did not belong to the state. The tailings, amounting to nearly 8-million tons, came from the Hawkins mine, formerly operated by the International Harvester Co., between 1923 and 1951. The court held, however, that the state owns the land under the lake and that a trespass was committed when the tailings were deposited there. The court ruled that the mining company had not abandoned the tailings, but had stored them in the lake until a process could be discovered for its economical treatment. The Hawkins Mine, through 1951, had produced 18,719,321 tons." (EMJ, Vol. 161, No. 4, April 1960, pp. 186-187). Cleveland Cliffs closed the Hawkins mine in 1961, and during the winter of 1962-1963, the Hawkins washing plant and associated buildings were disassembled and removed from the landscape. During its years of operation (at O'Brien Lake and at the mine), the Hawkins treated over 25 million tons of sandy ore. (L.F. Heising and R.C. Briggs, The Mineral Industry of Minnesota, pp. 591) The development of iron ore beneficiation, or the concentrating of low-grade ores, in the Lake Superior Iron District created immense social and economic benefits, but it also produced environmental consequences. In the western Mesabi range, low-grade iron ore concentration provided mining companies with a technological fix to the problem of silica-laden wash ores, that were previously considered valueless. The ability to process low-grade ores into a concentrated, profitable medium also helped prolong the life cycle of many of the high-grade mines and the mining communities in the Lake Superior District, and lessened the potential dependence on foreign ores to quench the nation’s growing thirst for steel. Although low-grade ore processing and concentration helped expand and extend the iron mining industry, it also produced environmental legacies that have outlived the majority of the mines and mining communities that were responsible for creating them. Like all of the other ghost plants, the Hawkins concentrator at Nashwauk is visibly absent from the landscape. Its social and economic legacies have been forgotten - hidden in dusty trade journals and consolidated into a small collection of bankrolls. What does remain of the Hawkins ghost plant is the ecosystem modifications that it created at O'Brien Lake. The processing of low-grade ores created new challenges for iron mining companies and mining communities. These challenges were rooted in how to acquire the billions of gallons of water required for washing and laundering purposes, as well as where to deposit the millions of tons of tailings they produced in the concentrating process. In terms of tailings, the operators at the Hawkins concentrator had a number of options, they could construct a basin for the tailings or excavate a pit to dump them in, but these were costly endeavors - the most inexpensive option was to simply dump the tailings into O'Brien Lake - which the Hawkins plant did.

1 Comment

Tim Holman

2/7/2018 10:24:56

Does anyone know of or heard of the origins of The Hawkins Club in Nashwauk, Minnesota?

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorJohn Baeten holds a PhD in Industrial Heritage and Archaeology from Michigan Technological University. His research aims to contextualize the environmental legacies of industrialization as meaningful cultural heritage. Archives

May 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed