|

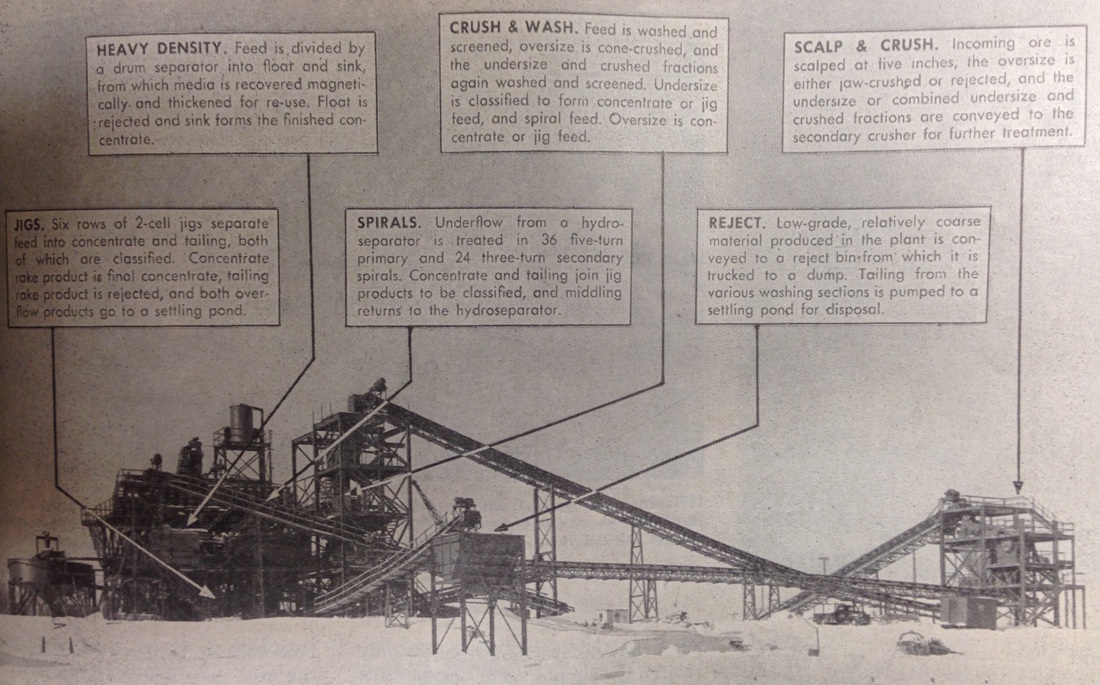

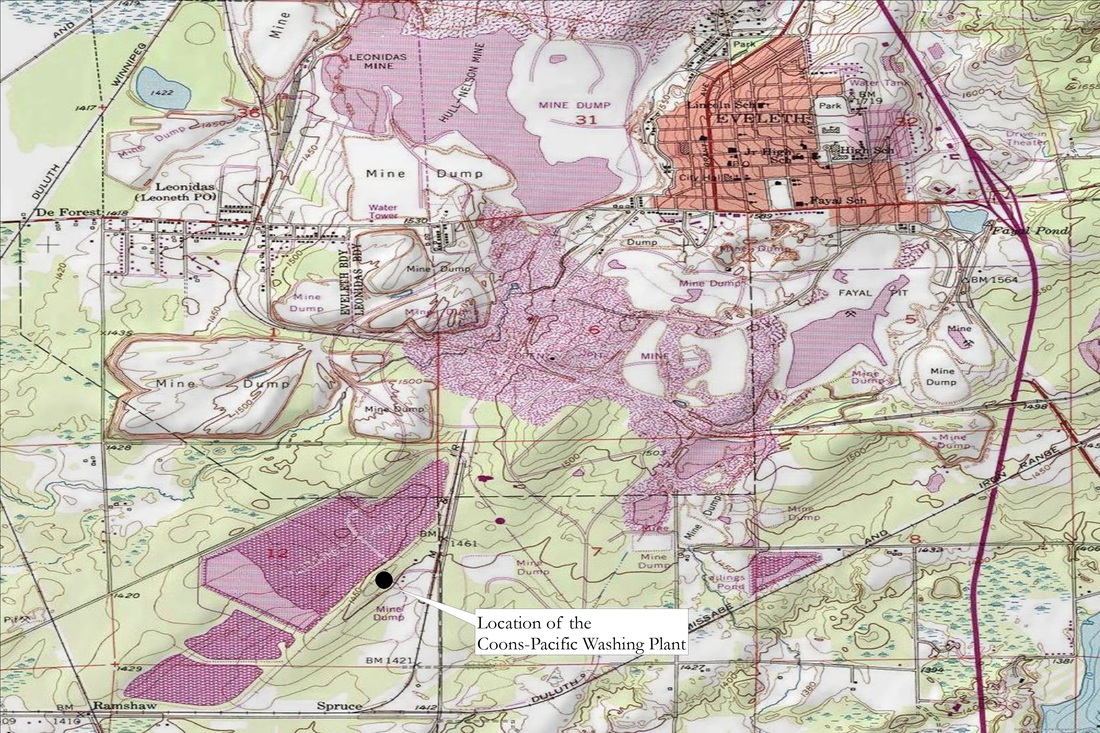

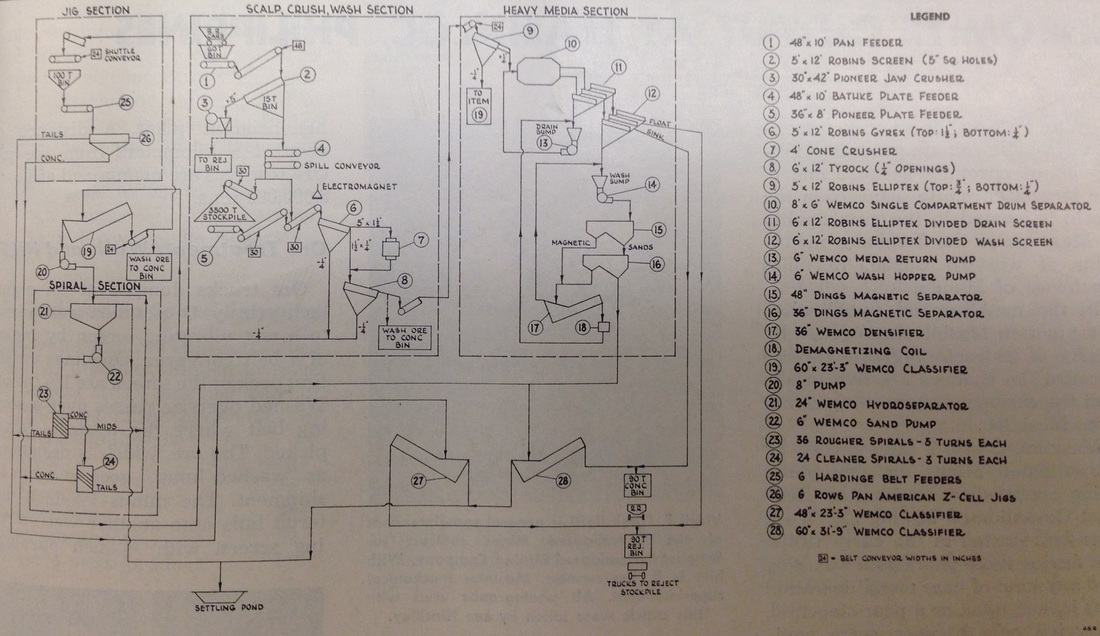

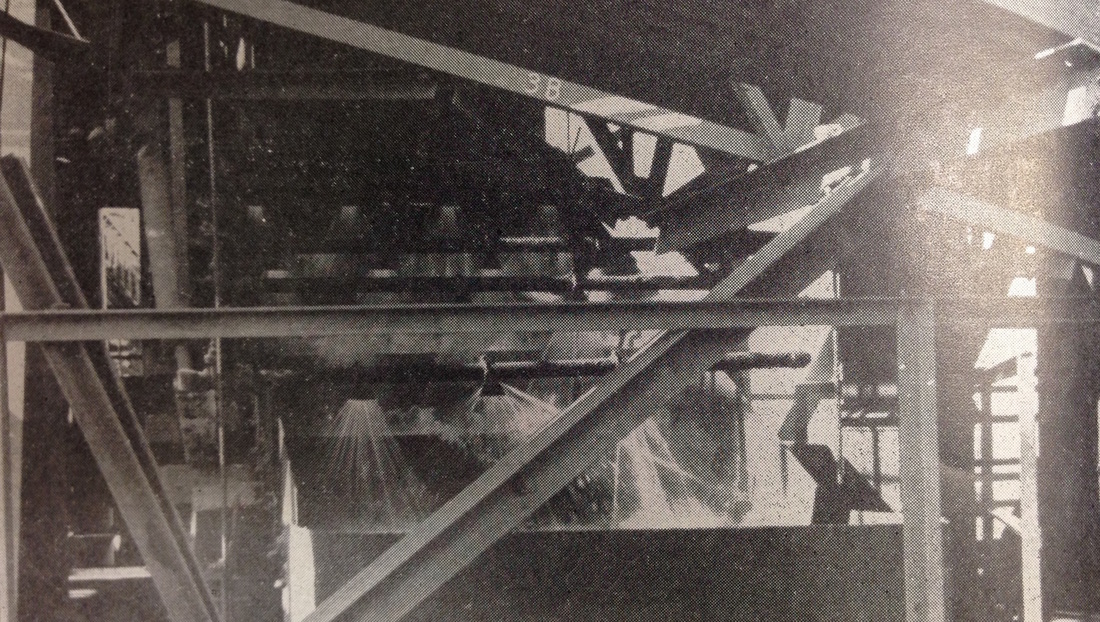

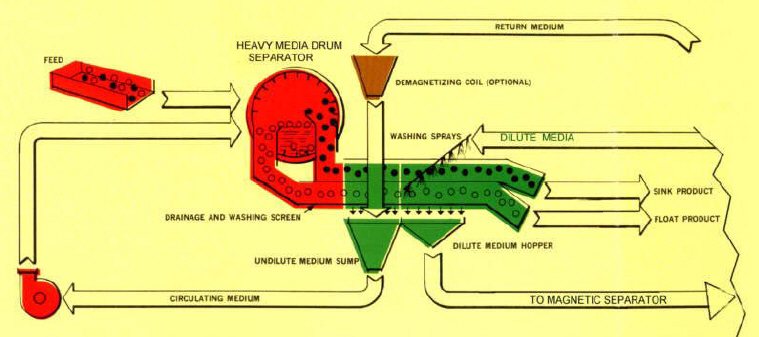

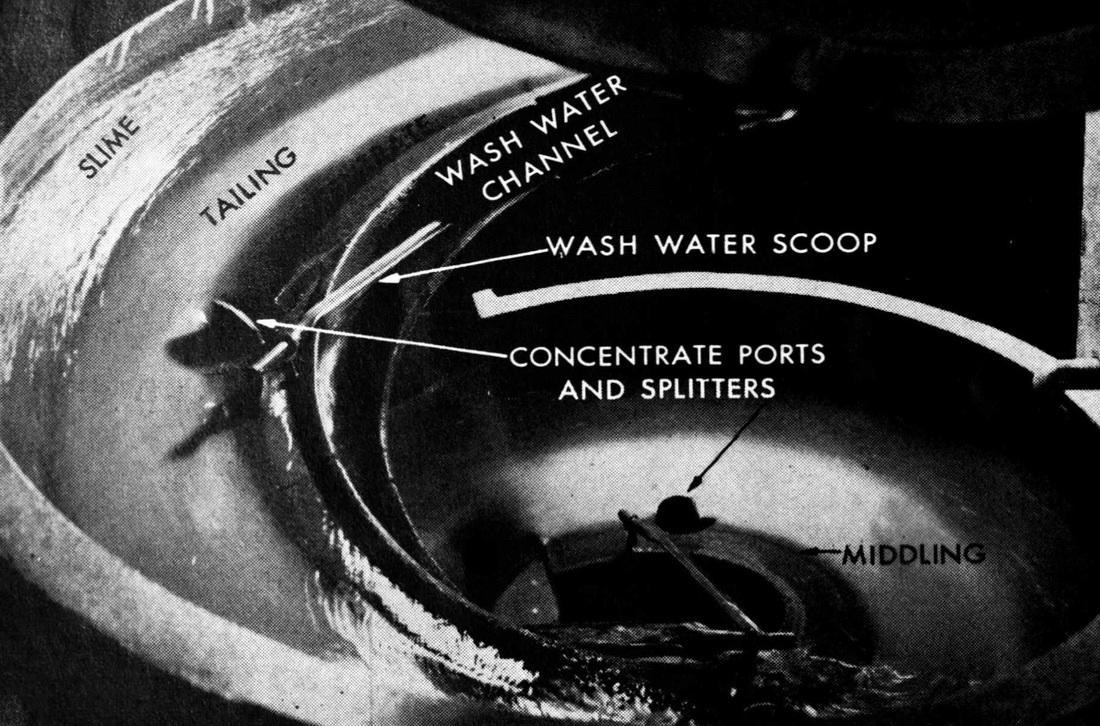

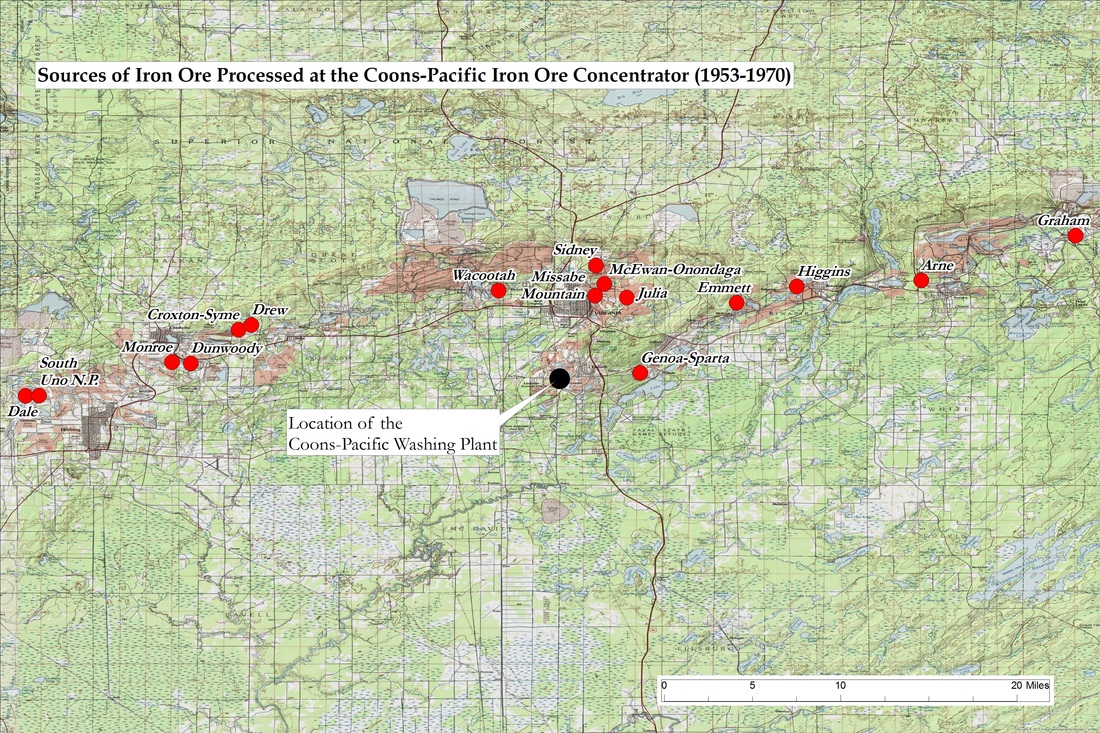

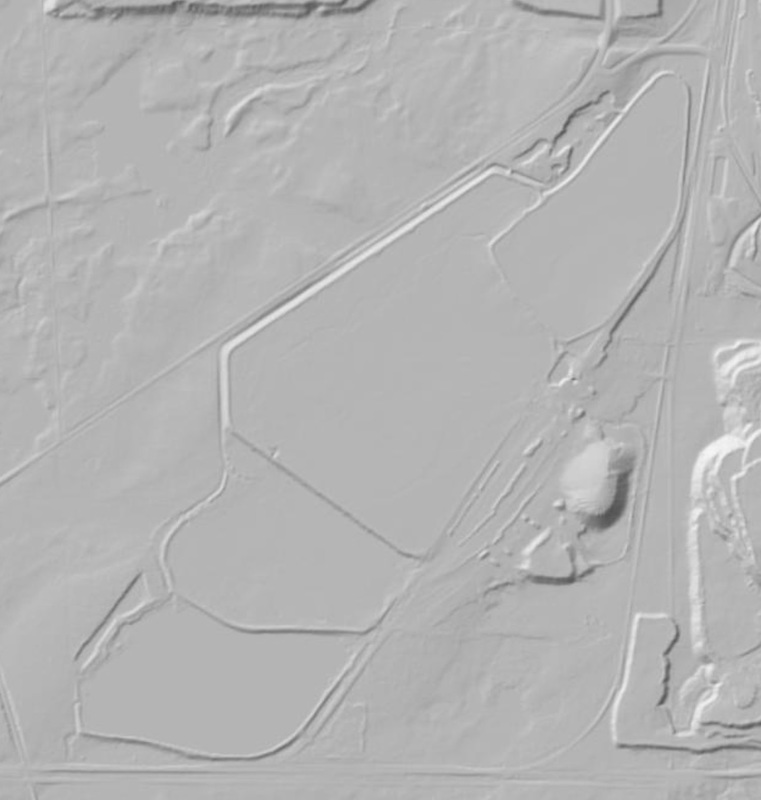

"In essence, the entire plant has the flexibility of a laboratory." (R.L. Burns, "Custom Milling Mesabi Iron Ores", in Mining World, July 1953, pp. 43) Located at the southwestern corner of the intersection of Grant Ave. and Monroe St. in Eveleth, MN, stands the world's largest free-standing hockey stick (and puck) - over 100 ft. in length and weighing in at 5 tons (the largest hockey stick is actually in Canada and is nearly twice as long as the monument in Eveleth). Dubbed by locals as the "Stick", the landmark was first dedicated by the city of Eveleth in 1995, and after seven years of harsh northern Minnesota winters the "Stick's" aspen body began to deteriorate, leading to the erection of a new "Big Stick" (measurements above) in 2002. The "Big Stick" and the associated US Hockey Hall of Fame serve as tourist attractions for the community of Eveleth, designated as "The Capital of American Hockey" - but Eveleth's contemporary hockey heritage owes much to its industrial past and the large open pit mines and processing plants that fueled the city's cultural and environmental landscape for nearly a century. Located in the far eastern extent of the Mesabi Range - a region known more for its rich supply of direct shipping ore and taconite deposits than for low-grade washable ore - the community of Eveleth was also home to the Mesabi's first custom beneficiation plant - The Coons-Pacific Iron Ore Concentrator - a product of savvy engineering and corporate foresight.  Coons-Pacific Plant - (Skillings' Mining Review, 31 Oct. 1953, pp.4) Coons-Pacific Plant - (Skillings' Mining Review, 31 Oct. 1953, pp.4) The Coons-Pacific washing plant was a custom beneficiation plant built in partnership by the E.W. Coons Mining Co., and The Pacific Isle Mining Co., as a facility to process ores from their mines near Eveleth, MN. A custom mill is a processing facility that treats diverse ores, meaning that its flow sheet has built in flexibility, rather than those mills that were tailored to only process ore from an individual mine. Built in 1952, and with a daily capacity of 300 tons, the Coons-Pacific Washing Plant originally treated ores from the nine mines operated by the E.W. Coons Co. and Pacific Isle located in the far eastern portion of the Mesabi Range. Since it generally wasn't economically practical for smaller mines to design and construct their own beneficiation plants, custom mills were developed in the mining industry to function as specialized facilities- acting as middle men between individual mines and secondary processing facilities such as blast furnaces and smelters. The Coons-Pacific was designed with five distinct sections for treating low-grade ore: a scalping (removal of dirt, foreign material and general crud by means of vibration) and crushing section; a washing section; a Heavy Media Separation (HMS) section; a jigging section; and a spiral section. The design of the Coons-Pacific Concentrator drew from the success of Pacific Isle's portable North Uno concentrator (the next post in this series) which treated low grade ores in the Mesabi since the late 1940s. However, unlike many other beneficiation plants, such as the Trout Lake Concentrator, the equipment of the Coons-Pacific was arranged without a "building to house it - made possible by the fact that the plant only operated during the shipping season." (Skillings' Mining Review, 31 Oct. 1953, pp.4) The design of the Coons-Pacific flow sheet allowed so "that any time any size fraction may be rejected, sent to a concentrating section, or loaded as a concentrate. In essence, the entire plant has the flexibility of a laboratory." (R.L. Burns, "Custom Milling Mesabi Iron Ores", in Mining World, July 1953, pp. 43) During the Coons-Pacific first years of operation, the beneficiation plant eventually treated ores from over 20 different mines, processing between 100-120 cars of ore daily. This material was composed of varying grades, which required a variety of ore processing equipment found in the processing sections of the Coons-Pacific Concentrator's flow sheet. (Skillings' Mining Review, 7 Nov. 1953, pp.4). The first step in all beneficiation plants is converting crude ore into a medium that can be effectively fed into a concentrator. This generally involves some degree of primary crushing, as well as screening or classifying the ores into sizes - either oversized or minus-grade and undersized ores - which were amenable to concentration. At the Coons-Pacific plant, oversized material was any ore that failed to fall through one of the many 5-inch slots that made up the surface of a vibrating screen, or grizzly. A grizzly is simply a series of parallel bars with uniform spacing that is used to classify ore by a specific size. The oversized material was crushed in a jaw crusher to an appropriate size, or was picked off and hauled to the reject pile as waste. It is important to note that not all material sent to a beneficiation plant was actually ore. Ore is an economic term, meaning that the material contains something of value. If the pickers at the grizzly deem that some of the material is not ore but gangue or waste, it was rejected for treatment. The undersized material that passed through the 5-inch slots of the grizzly was sent next to the washing section (see image above), which processed the ore by wet screening, a process that involved the ore traveling down a series of vibrating screen as jets of water helped disarticulate the ore from its associated loose gangue. The washing section further classified the ore into three sizes, with the largest ore, that material greater than 1 1/2- inch sent to a secondary crusher while the remaining fines were treated on a second wet screen with a smaller classifying system than that used by the first. The classified material was next sent to either a concentrate bin, or it was processed further, with coarser material sent to the HMS section while the fines were sent to either the spiral section or the jigging section. (R.L. Burns, "Custom Milling Mesabi Iron Ores", in Mining World, July 1953, pp. 43) The purpose of ore concentration is to take a large amount of economically negligible material and convert it into a more compact and profitable commodity. The next processing sections in the Coons-Pacific concentrator were some of the more sophisticated beneficiation methods employed in the Mesabi during the 1950s. Heavy Media Separation (HMS) at the Coons-Pacific Concentrator involved a trommel like device called a Wemco drum separator, that rotated on an axis and relied on gravity and centripetal force to help concentrate the ore. Once in the HMS section, ferro-silicon was added as a separating medium to the fine washed ore which helped classify the lighter waste material as float product, and the heavier ore as sink product, which eventually found its way to the concentrate bins. In the washing section at the Coons-Pacific Concentrator, the finest material (that under 1/4-inch) was treated in a Wemco classifier - a long tilted machine that looks like a massive slow turning auger placed within an open box. Inside the classifier the fines were mixed with water and as the classifier's auger rotated, the content that spewed over the edges of the box was sent to the jigging section. Jigs were used to concentrate very fine washable ores. Jigs utilized gravity much like the Wemco classifier described above to concentrate ore, but jigs were arranged vertically and relied on a slow plunging effect that would cause lighter material to overflow from the sides of the jig as waste, while heavier, valuable material concentrated towards the base of the machine. The overflow from the jigs was hauled to the tailings pond while the concentrated ore was sent to the concentrate bins. While HMS and jigging were both well developed concentrating techniques used in the Mesabi beneficiation plants, spiral concentration was still a somewhat novel process, not introduced to the range until 1947. (Judson Hubbard, "Spiral Concentration", in Mining World, Sept. 1948, pp. 41-44) Like most forms of concentration, the spiral section also relied on gravity and the equipment's shape to help concentrate heavier material towards the center of the spiral as the feed traveled downward towards its base. The Coons-Pacific Concentrator was equipped with 36 spirals, each of which had 5 turns, or levels in which the ore spun around the machine. (R.L. Burns, "Custom Milling Mesabi Iron Ores", in Mining World, July 1953, pp. 45) All of these concentrating methods created waste - some coarse and others fine. In the Coons-Pacific Concentrator two distinct types of waste were produced - tailings and waste rock. The tailings at the Coons-Pacific Concentrator were those fine materials that overflowed in the concentrating sections, as they happened to be lighter and less dense than the concentrated iron ore. These tailings were pumped into nearby settling ponds. The coarse waste rock was dumped adjacent to the plant, close to the crushing and scalping section, as the majority of this never ventured farther than the scalping table. Unlike nearly every other beneficiaton plant in the Mesabi Range, the Coons-Pacific never stockpiled ore. Instead, the concentrates from the plant were shipped out regularly on the rail lines that ran around the beneficiation yard. By 1960, the Coons-Pacific Concentrator was treating 1.5 million tons of ore - roughly five times the annual capacity of ore it processed during its opening year. (Matthew Sikich, The Mineral Industry of Minnesota, pp. 554) When the Coons-Pacific Concentrator first opened in 1952, it treated low-grade ores from nine mines: the Croxton-Syme, Drew, Emmett, Genoa-Sparta, Graham, Julia, Missabe Mountain, Sidney, and the Wacootah. Additional mines began to ship ore to the Coons-Pacifc, and during the 1969 season the concentrator was treating ore from eight other mines, including the Arne, Dale, Dunwoody, Higgins, McEwen-Onondaga, Monroe, and the South Uno. (R.L. Burns, "Custom Milling Mesabi Iron Ores", in Mining World, July 1953, pp. 45; and Keith Olson and Ella Humenansky, "Mineral Industry of Minnesota", pp. 417) In 1968, Pacific Isle Mining Co. suspended its mining operations and the newly formed Coons Pacific Co. assumed ownership of the Coons-Pacific Concentration plant. By 1969, the Coons-Pacific Concentrator was subsumed by the larger Pittsburgh Pacific Co., who apparently operated the plant until the early 1980s. I've been unable to locate reports of the Coons-Pacific's closure, but from analyzing aerial imagery and examining published production totals from Pittsburgh Pacific mines, I believe the Coons-Pacific shut down around 1982. The scrapping and removal of the plant likely happened soon after, as by 1989 all that remains of the plant are the concrete pads that once supported the five concentrating sections, pockmarks of concentrating bins, and the linear routes of abandoned rail lines. The walls that supported the massive tailings basin remain, as they do at the majority of the ghost plants in the Lake Superior Iron District- the ubiquitous vestiges of a forgotten envirotechnical system within a postindustrial landscape. Today, the triangular shaped tailings basin produced from the Coons-Pacific Concentrator is the most visible signs of the plant's existence - and like other ghost plants, this waste serves as the Coons-Pacific Concentrator lasting legacy on the postindustrial landscape. The waste piles produced from those industries whose business it is to extract and process mineral deposits have a tendency to outlive the mines, plants and mining engineers who created them.

With the exception of the tailings produced by the Reserve Taconite Plant at Silver Bay, MN (which sent its tailings directly into Lake Superior), the waste piles from iron beneficiation in the Lake Superior Iron District are not ghosts - in fact they often serve as the last physical reminders of a forgotten and scrapped industry. Although the square concrete footings of the Coons-Pacific Concentrating Plant remain visible, they are dwarfed by the triangular tailings pond and its distinct geometric walls - appearing more like Incan geoglyphs than the rejects of beneficiation.

1 Comment

|

AuthorJohn Baeten holds a PhD in Industrial Heritage and Archaeology from Michigan Technological University. His research aims to contextualize the environmental legacies of industrialization as meaningful cultural heritage. Archives

May 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed