|

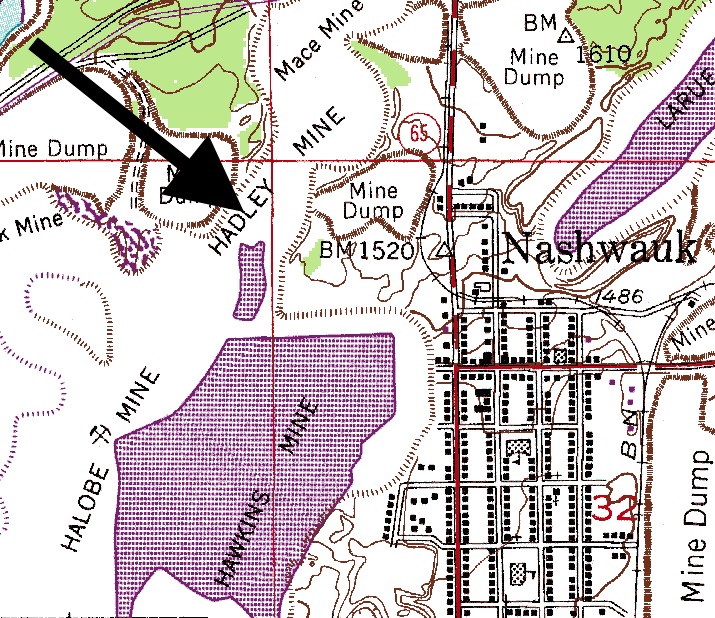

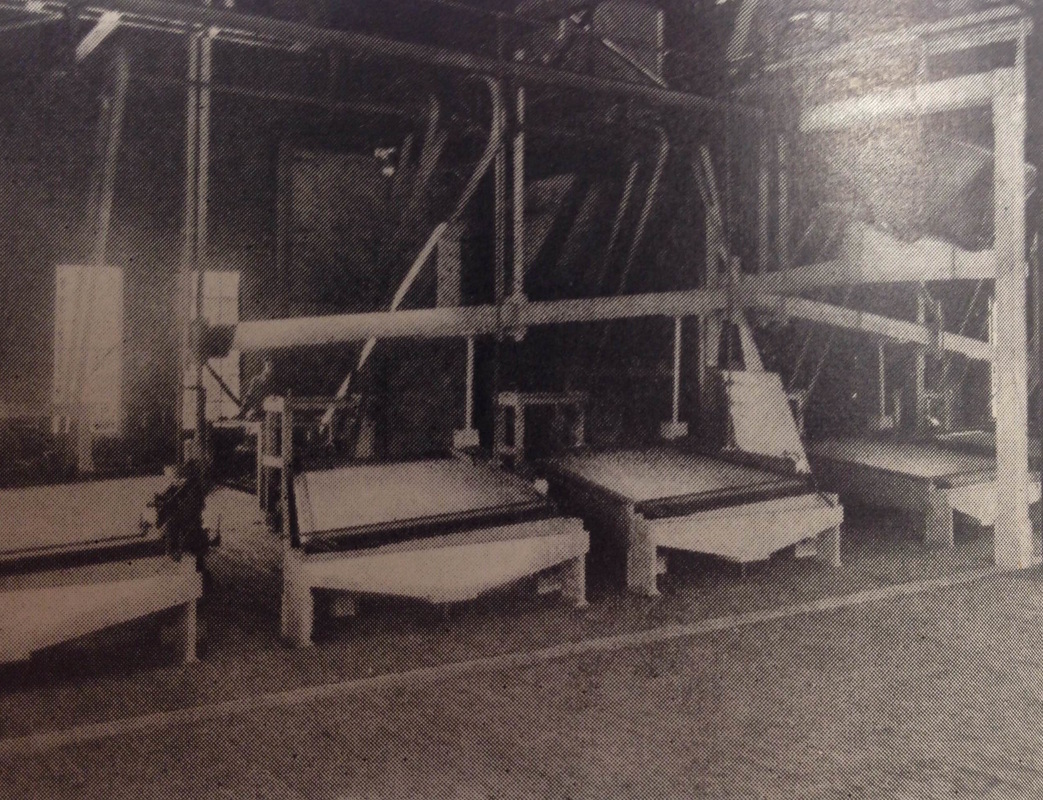

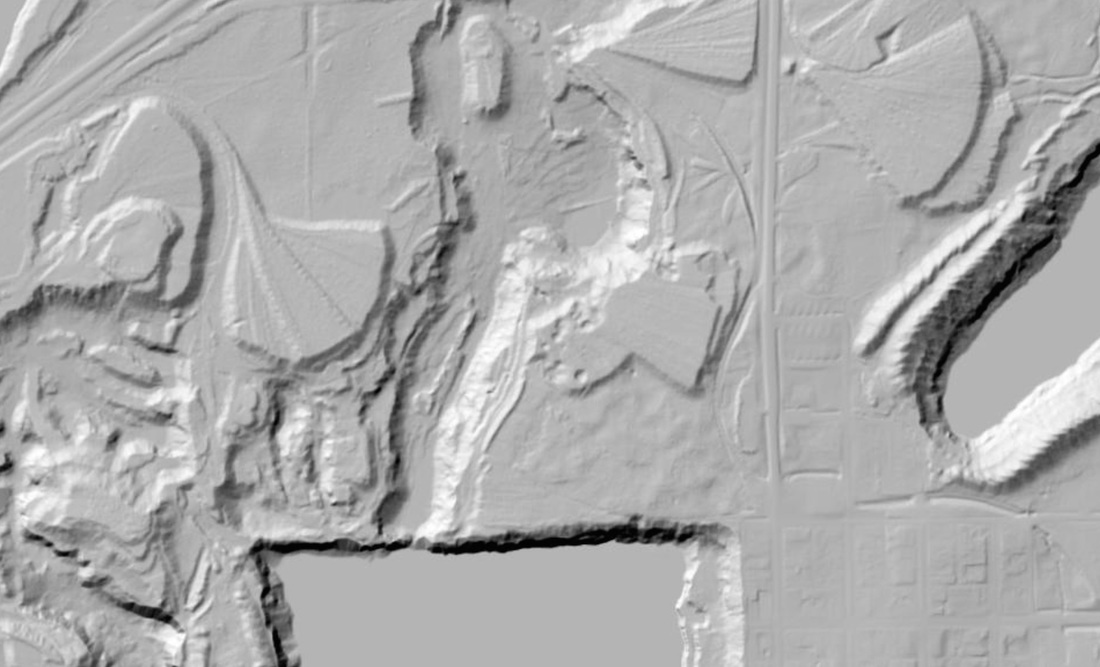

"The washing of iron ore means more than most people realize...The evolution of the concentrating process has allowed the development of iron-ore deposits that have brought millions to the owners, to the operators and to the public." Nashwauk, MN is located in Itasca Co, within the western branch of the Mesabi Range, a geologic region known historically for its abundance of low-grade, siliceous iron ores. These ores, unlike the direct shipping ores that brought fame and fortune to the Vermillion Range, were encased in the earth like baklava, with thin layers of silica gangue mixed with thin layers of iron ore. Mining engineers and furnace operators found this ore to be irritable, and when fed directly to the blast furnaces it caused a sort of industrial indigestion as the high-silica content in the ore had a tendency to clog-up the furnace's innards. "The Crosby plant, which is typical in size of the others, is a steel structure with dimensions of 62 x 67 ft. and has an extreme height of 81 ft. The machinery is all of Allis-Chalmers manufacture." L.A. Rossman, "Nashwauk Iron-Washing Plants", in Engineering and Mining Journal, Vol. 102, No. 12, Sept. 16, 1916, pp. 491 Mining at Nashwauk started around the turn of the twentieth century, beginning first with the Hawkins and La Rue mines in 1903, and followed by the Crosby mine in 1906. The Crosby mine began as an underground mine, but unlike many of the underground mines seen in other parts of the country, it appears that the Crosby mine employed the slicing method. Underground slicing involved sinking a vertical shaft into the ore deposit, and then running horizontal drifts from the shaft. Within these drifts, miners would begin working at the farthest reaches and retreat backwards towards the shaft, allowing the roof of the drift to collapse as they retreated. Using this method, the miners continue to work downward from the surface of the mine to the base of the shaft. "In the underground Crosby mine at Nashwauk there are two steam shovels...The shovel on the West 40 loads the ore into the cars and they are taken to the shaft by electric motors. The shovel on the East 40 shovels the ore into mills from where the ore is loaded into cars from chutes and taken to the shaft, from which place it is hoisted to surface by electric power, and dumped onto grizzlies, the fine ore going down into the steel cars below and the rock and large chunks of ore are picked off the grizzlies by men employed for that work." (Dept. of Labor and Industries of the State of Minnesota 1915-1916, pp. 145) The erection of concentrating plants at Nashwauk followed a similar trajectory as the mines, with the one-unit Hawkins plant going into operation during the 1912 season and the La Rue concentrator the following year. The Crosby Washing Plant was constructed by the Cleveland Cliffs Iron Co. during the 1915 season, and by 1917, the 1/2 unit washing plant, with a 300,000 ton capacity, was in operation. The Crosby plant was the smallest washing plant in the Nashwauk region, having a daily capacity of roughly 1/10th that of the Trout Lake concentrator at Coleraine. Within the Crosby plant the ore was concentrated on five Overstrom tables (see image below). Both photos from the Engineering & Mining Journal, Vol. 102, No. 12, Sept. 16, 1916, pp. 492 These Overstrom tables, which acted like sluice boxes on steroids, were set on a slight tilt and had riffles running length-wise along their plane. The crushed iron ore and water would be fed onto these tables and an agitating motor would shake the table, causing the lighter silica and water to flow towards the tilted discharge as tailings, while the heavier iron would be captured by the riffles and sent to the concentrate side of the table. "The Crosby mine has been closed indefinetly. This is the second Cleveland-Cliffs property to close recently. Over 100 men are affected. It is possible that the washing plant will be operated to handle the underground stockpile." Engineering and Mining Journal, Vol. 111, No. 21, May 21, 1921. Although the Crosby Mine was a fairly short lived operation, approximately 15 years of production, much was written about the plant when it was first constructed. Following its closer in 1921, the mine sat idle for about seven years until it was re-opened by the Butler Brothers as the open-pit Hoadley Mine. The Hoadley Mine sent its ore to the nearby Harrison concentrator (covered in a later post). Much like other mines in the region, the transition to large scale open-pit mining eventually consumed even the faintest sign of the former Crosby Mine and Washing Plant, two more ghosts on the Mesabi landscape. In terms of the Crosby mine, it was an economically menial producer when compared to other mines in the western Mesabi. The Crosby washing plant, too, was neither innovative like the La Rue, nor lasting like the Trout Lake. The Crosby mine and washing plant's cultural and environmental footprints have been seemingly washed away by the tides of a transitioning industrial landscape, reworked and rewashed as new technologies find ways to profit off of historic waste.

In the fall of 1910, two immigrant laborers, Sam Alto, 29, from Finland, and Blazo Peakovitch, 22, from Montenegro, were killed within the depths of the Crosby Mine. Sam Alto was employed on a timbering crew, erecting a subterranean support structure within the drifts of the mine. While Sam was setting timbers, a crew of miners in a level above him set off a dynamite charge, sending a blast of rubble into Sam's drift and on top of him. Sam was buried under a pile of taconite, a valueless material in 1910, dying of asphyxiation. Blazo Peakovitch worked as a trammer, operating the brake system on the underground locomotive that moved iron ore from the drifts to the hoisting shaft. As the train moved from the drifts towards the shaft, Blazo apparently lost his balance and fell under the moving machine. The ore cars bounded over his body, crushing his skull. Sam and Blazo are just two of the many ghosts that lived and worked within the ghost mines and ghost plants of the Lake Superior Iron District. It has been said that the first step in the heritage process is recognition - acknowledging first that something existed, and second that it produced something meaningful. Whether or not abandoned mines and ghost plants like the Crosby did so is up for debate, but I think their stories, and the stories of workers like Sam and Blazo serve as important and meaningful reminders of our industrial past as we work towards creating a safer and healthier post-industrial future.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorJohn Baeten holds a PhD in Industrial Heritage and Archaeology from Michigan Technological University. His research aims to contextualize the environmental legacies of industrialization as meaningful cultural heritage. Archives

May 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed