|

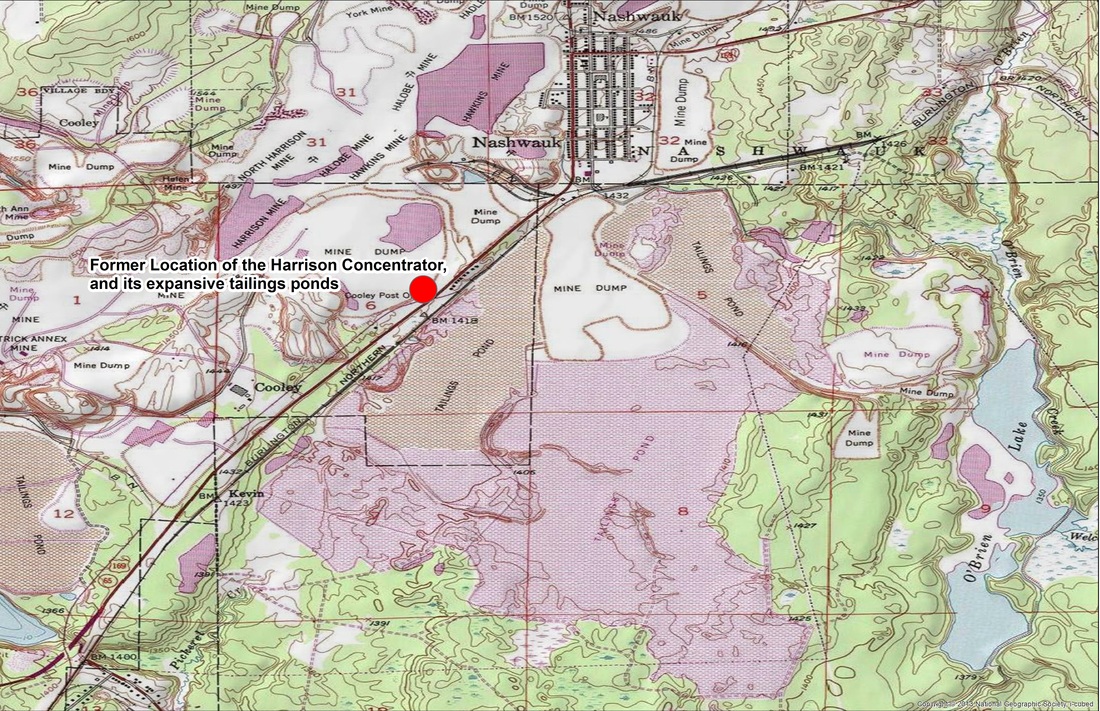

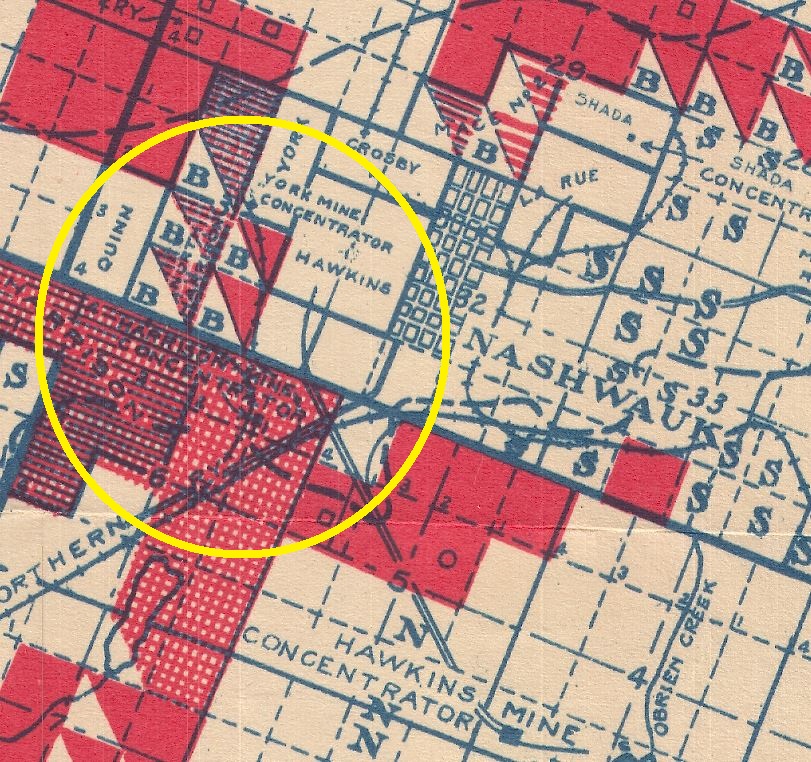

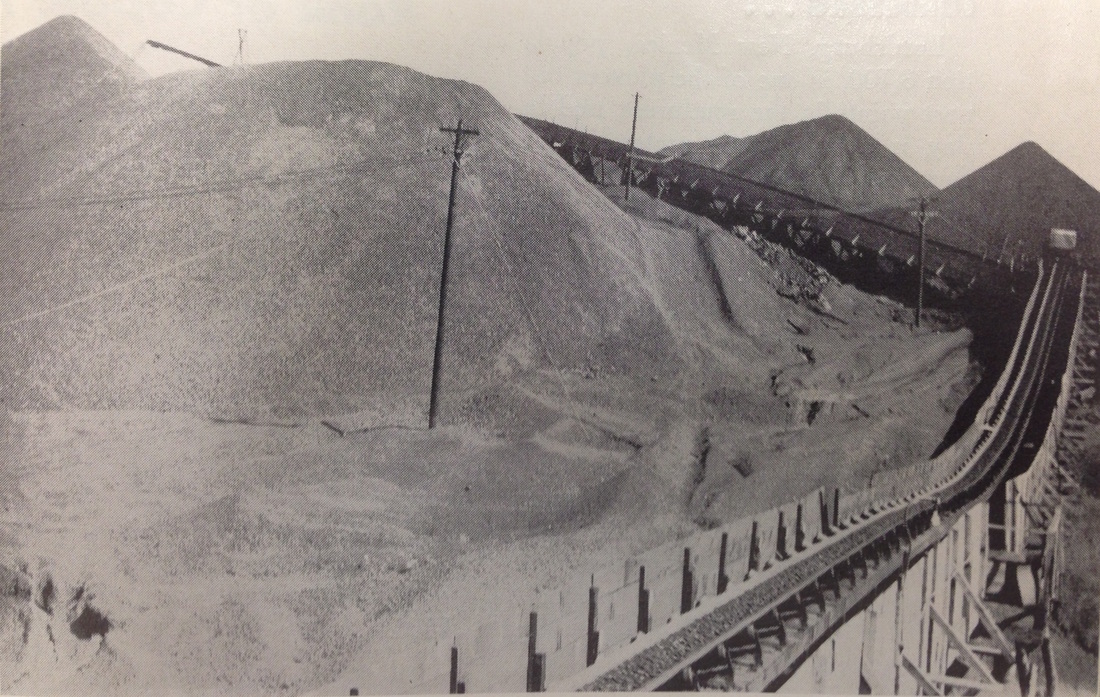

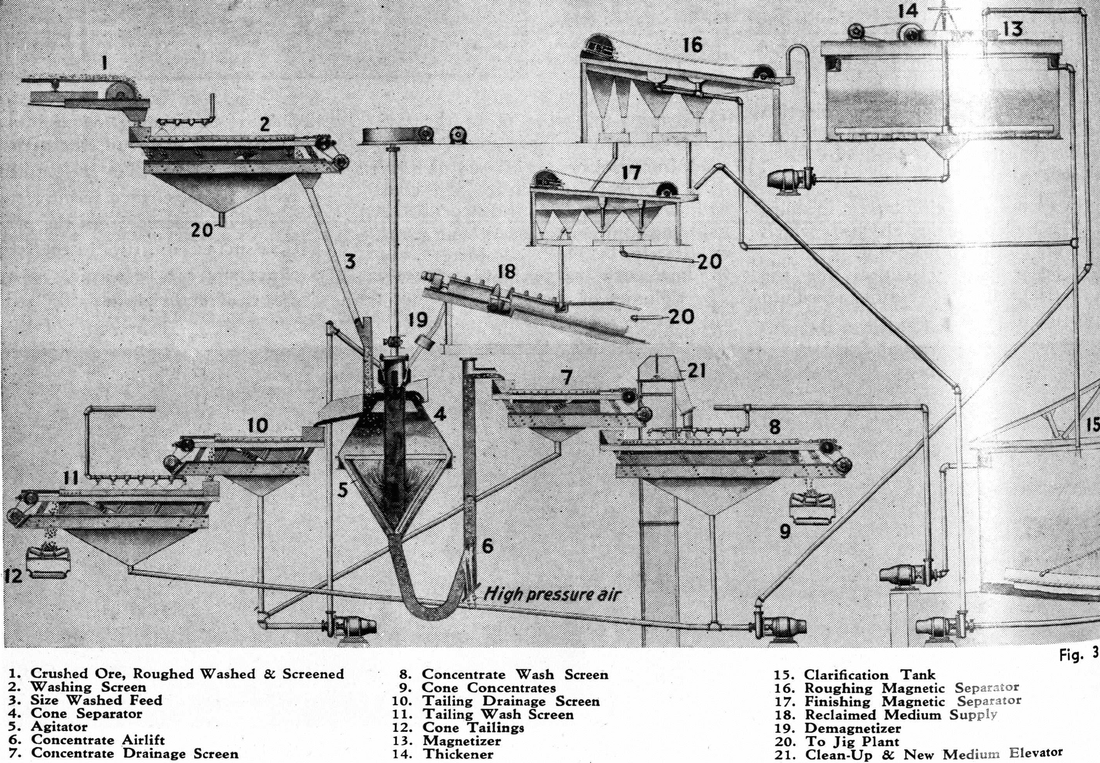

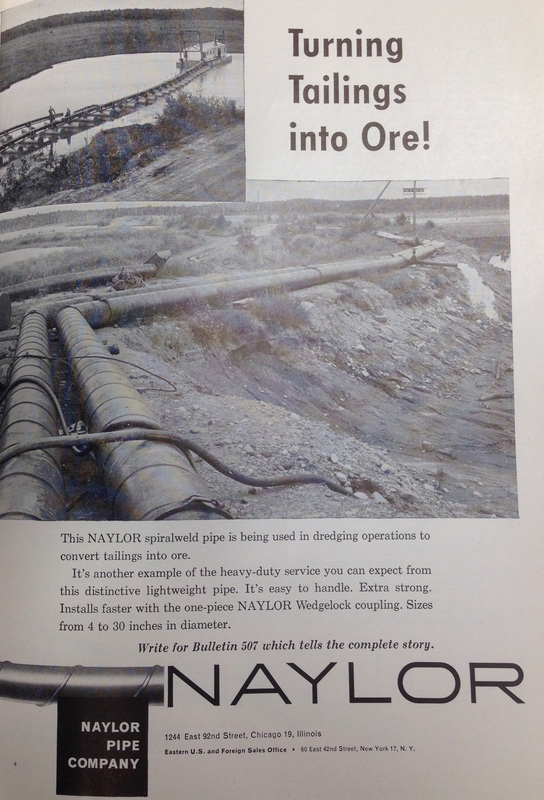

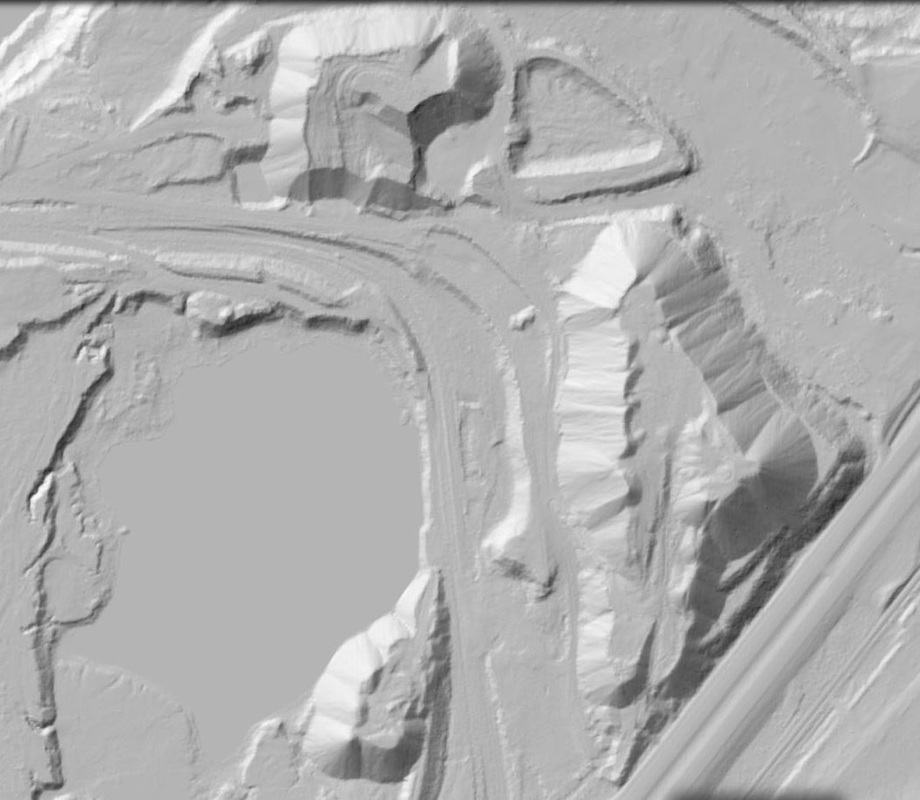

Ore is an economic term Fred Quivik, 2015 I've been fortunate to work with a number of great mentors and colleagues during my time as an archaeologist for the Forest Service, and as a graduate student at Michigan Tech. A benefit of being in academia is the opportunity to listen to other researchers present their own work. A recently retired history professor from MTU, Fred Quivik, who I've worked with during my MS and PhD research, presented a paper in November of 2015 on mill tailings in Montana. During this talk Fred highlighted an important fact, one that I had overlooked as I've studied mining - simply that "Ore is an economic term". Whoa! That cogent sentence changed the way I understood the mining industry, and changed the way I looked at concepts like value and waste. In mining, what is value today, might be waste tomorrow - and vice-versa - judgments based on economics, technological development, and culture. In mining heritage we can see similar parallels, as what we value collectively can change with time, with politics, and with economics. Both of these fields, mining and mining heritage, ascribe value judgements to things, such as minerals, machines, and memory, based on shifting, and abstract cultural constructs. Since Fred's talk and as my research has progressed, I've found myself writing and reflecting about concepts like value and waste - especially how it relates to mining, heritage, and the environment - examining closely the often blurry line that we draw to divide the two. I will return to this idea later - but for now we will explore the history of the Harrison Concentrator, the third beneficiation plant constructed in the Mesabi Range, which the Butler Brothers Mining Co. used to convert a material previously considered waste into an abundant source of value in the form of iron ore concentrates. Unlike other iron ranges, from its inception in the early 1890s, the Mesabi Range has been dominated by open-pit mines. When a mining company wants to develop an open-pit mine, one of the first steps is to expose the iron ore deposit itself, effectively isolating value- or the ore- from the surrounding waste. Exposing a shallow ore deposit involved peeling away the organic layers (called overburden) from the mineral deposit which it was encasing. The Butler Bros. of St. Paul were a prominent mine-stripping company active in the Mesabi Range during early part of the 1900s. By 1914, Butler Bros. expanded their activity from mine developing toward actual mining, and opened a swath of land just south of Nashwauk, and north of historic Cooley, MN, which contained a large quantity of low-grade washable ore. "Butler Bros., striping contractors and railroad builders, not long ago leased the Harrison property from the Great Northern interests, and this is now being operated jointly with the Quinn mine. One of the conditions of the lease is supposed to have provided that Butler Bros. build a concentrating plant having an annual capacity of at least 100,000 tons. It is known that Butler Bros. was recently in the market for such a plant, the estimates on the machinery having been furnished by a large Milwaukee concern. While the concentrator will eventually be installed, it is held up until next spring, probably because of the unsettled conditions, and particularly the low state of the iron market. In general, the design of this plant and the method of treatment are said not to vary greatly from that at the Nashwauk and Coleraine washeries, which have been in operation for some time and are giving good results. In addition, it is understood that one other concentrator is being planned for the Mesabi range, that of the M.A. Hanna Co. It is not known, however, what property this plant is for or whether it is a Hanna property." Engineering and Mining Journal, Vol, 98, No. 19, Nov. 7, 1914, pp. 850 As you will notice in the title of this post, the Harrison concentrator was also known as the Harrison-Quinn concentrator, due to the plant processing the ore from both mines. The dual naming of the plant made tracking down information on the plant a little tricky, since it might be labeled as either the Harrison concentrator, the Quinn concentrator, the Harrison-Quinn concentrator, the Quinn-Harrison concentrator, or the Cooley plant - I even thought they might be two separate plants to begin with - but I digress. The Harrison concentrator processed ores from nine separate mines, all within a relatively close 2-mile radius to the plant itself, including: the Harrison (1914-1967); the Quinn (1914-1965); the Crosby/Hoadley (1916-1950); the Mace No. 2 (1920-1959); the North Harrison (1915-1956); Harrison Annex (1923-1940); the North Harrison Annex (1925-1940); and the Halobe (1930-1959) - collectively called The Harrison Group. Note that the dates given for these mines include sporadic periods of inactivity. "Another $250,000 washing plant is now in operation along with several others which have been in operation for several years. It is estimated to treat 8,000 tons daily. This plant is located at Nashwauk, Minn., and at the Quinn mine. The washing plant was constructed this summer by Butler Brothers, a stripping company. At full capacity the plant will handle 8,000 tons of ore daily. It is the third washing plant constructed on the Mesabi range and is said to contain more modern equipment than either of the other two. The plant makes it possible to improve the grade of ore to such an extent that mineral which heretofore could not be shipped because of the mixture of sand, silica, and other foreign matter, after it has been treated at the washing plant it is of high grade." Skillings Mining Review, Vol. 4, No. 2, Oct. 16, 1915, pp.2 The Harrison concentrator operated from 1914 to the mid-1960s. Towards the end of its operating life, shipments from the Harrison Group were composed primarily of stockpile concentrates, rather than newly mined ores. During its operation the Harrison produced over 27-million tons of iron ore concentrates. To process that much ore, took even more water, nearly 25-billion gallons - used to help remove the lighter silica waste, and concentrate the valuable iron ore. During the winter of 1917, Butler Bros. began developing plans to expand the concentrator to a full-one unit, a size comparable to the nearby Hawkins concentrator (Iron Trade Review 01-04-1917). The one-unit size would help the concentrator process more ore per year, up to the 8,000 tons per day goal seen in the citation above. "There will be a good shipment of wash ores from the Nashwauk district of the Mesaba again this year. Butler Bros. is the most active operator and is loading ore from the Harrison, North Harrison, Quinn, Patrick and Kevin. The ore is treated in their Harrison washing plant, which handles 100 to 120 cars a day, and Patrick washing plant which is washing 60 or 70 cars daily." Skillings' Mining Review, Vol. 08, No. 10, July 26, 1919, pp. 10 From the time of its construction, the Harrison concentrator underwent continual modifications to its flowsheet, as Butler Bros. continued to implement new technologies in an attempt to capture more value. In 1929, a nearby beneficiation plant, the Stanley, was dismantled. The Stanley plant was equipped with the first system of jigs in the Mesabi Range, which upon dismantling were installed in the Harrison concentrator. By 1939, a process of heavy-medium separation was introduced to the concentrator, which used cone-separators to help further concentrate the iron ore. In 1948, the holdings of the Butler Bros., including the Harrison property, were sold to the larger M.A. Hanna Co, who operated it for the next twenty years. By the late 1950s, the low-grade deposit of the Harrison Group was becoming exhausted and the mine operated sporadically for the next decade - often shipping concentrates from stockpiles, rather than new ore. The Harrison concentrator was likely scraped by the Hanna Co. during the late 1960s, as the ore body from the once profitable Harrison Group became exhausted. Ore is not simply something that is dug out of the earth. This advertisement, for the still functioning Naylor Pipe Co., elucidates that the materiality of what is, and what is not ore, can change. That for a mineral to be considered ore, it needs to have some sort of value on the market. If there is not market value then it is not an ore. In this advertisement, the tailings that the dredge is reclaiming were once deemed waste, separated from value and laundered into a pond. But as new technologies developed and economic systems changed, so too did our perception of these tailings as waste, they now could exist as something entirely different. Suddenly they had value, that could be reclaimed and converted back into an ore. What remains of the Harrison concentrator is its footprint of transportation and waste. As I continue my research on low-grade iron ore mining in the Mesabi Range, waste continues to dominate the story.

What role can historical mining waste play in shaping contemporary environmental policy and mine management plans? Can valuing waste - in a heritage context - engage the public with not only how the waste got there, but what the waste consists of, how to best negotiate it, and why understanding its history matters? In terms of industrial heritage I believe that waste needs to be at the forefront of our current discussion, which is too often focused solely on tourism and preservation. What do you think?

3 Comments

6/21/2023 00:19:48

I enjoyed every chapter of this well done Blog.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorJohn Baeten holds a PhD in Industrial Heritage and Archaeology from Michigan Technological University. His research aims to contextualize the environmental legacies of industrialization as meaningful cultural heritage. Archives

May 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed