|

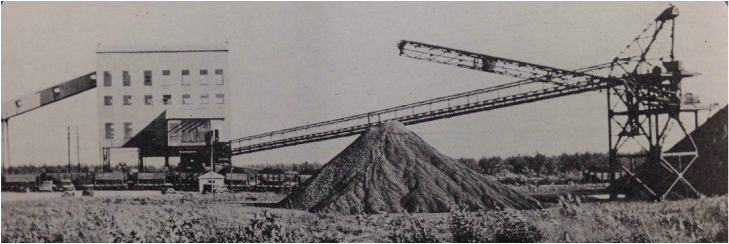

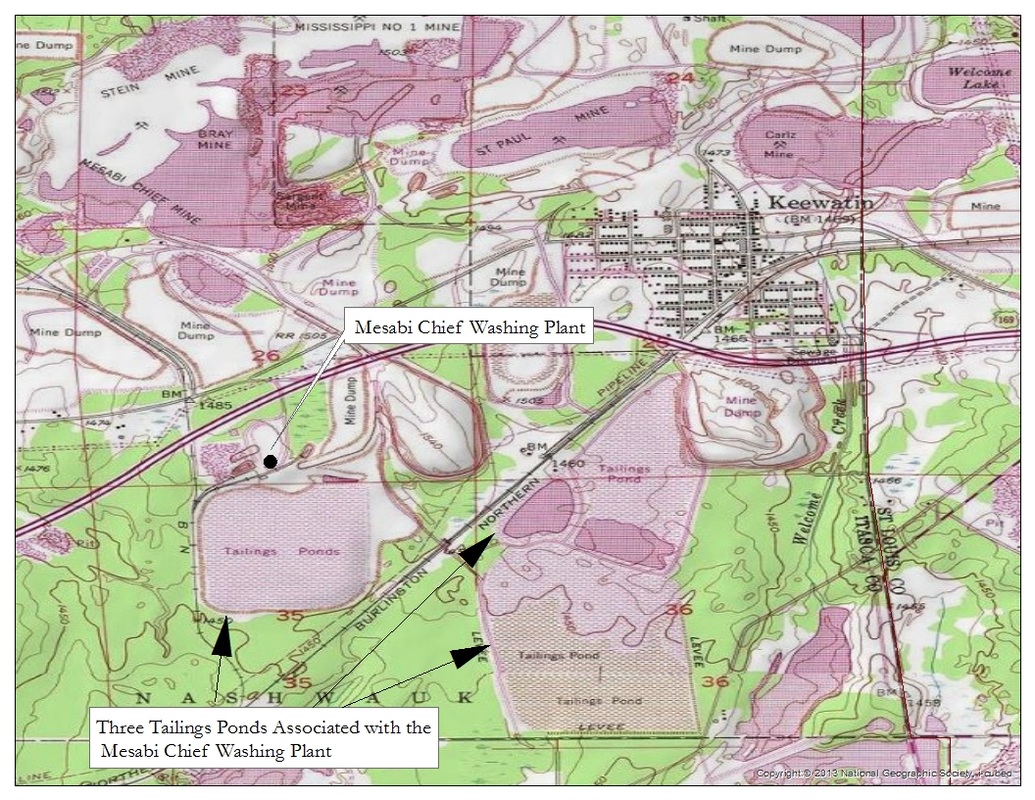

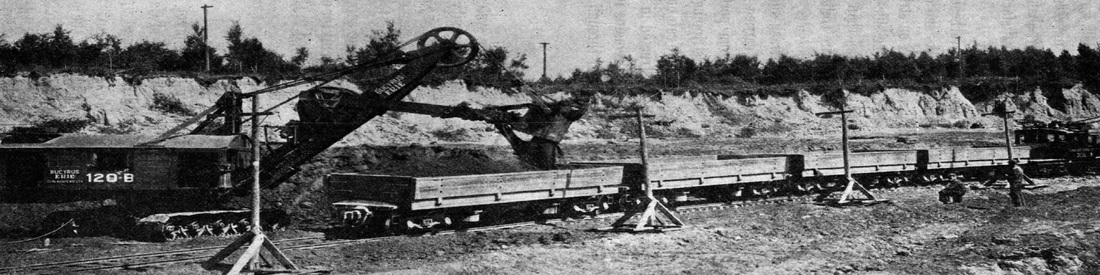

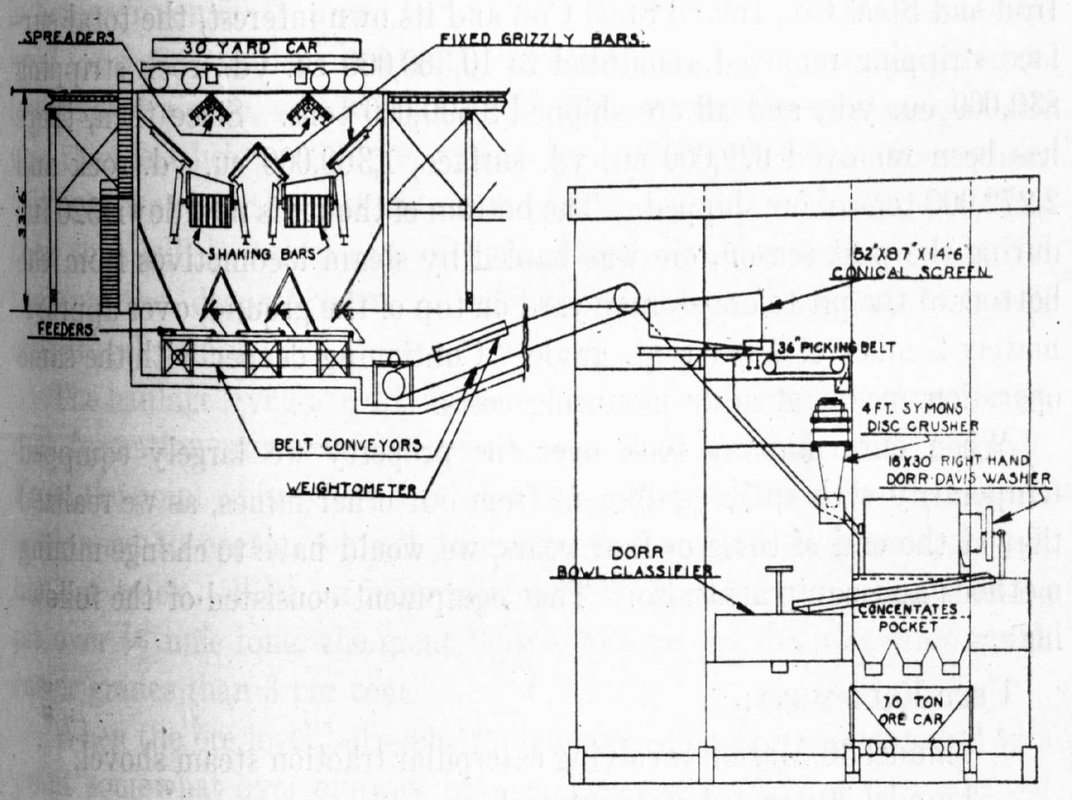

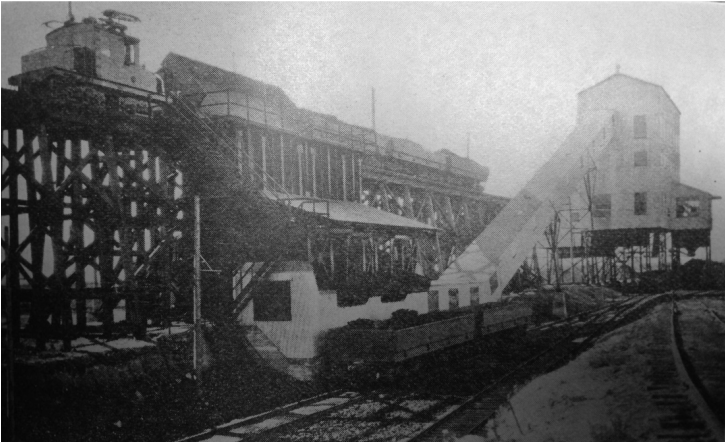

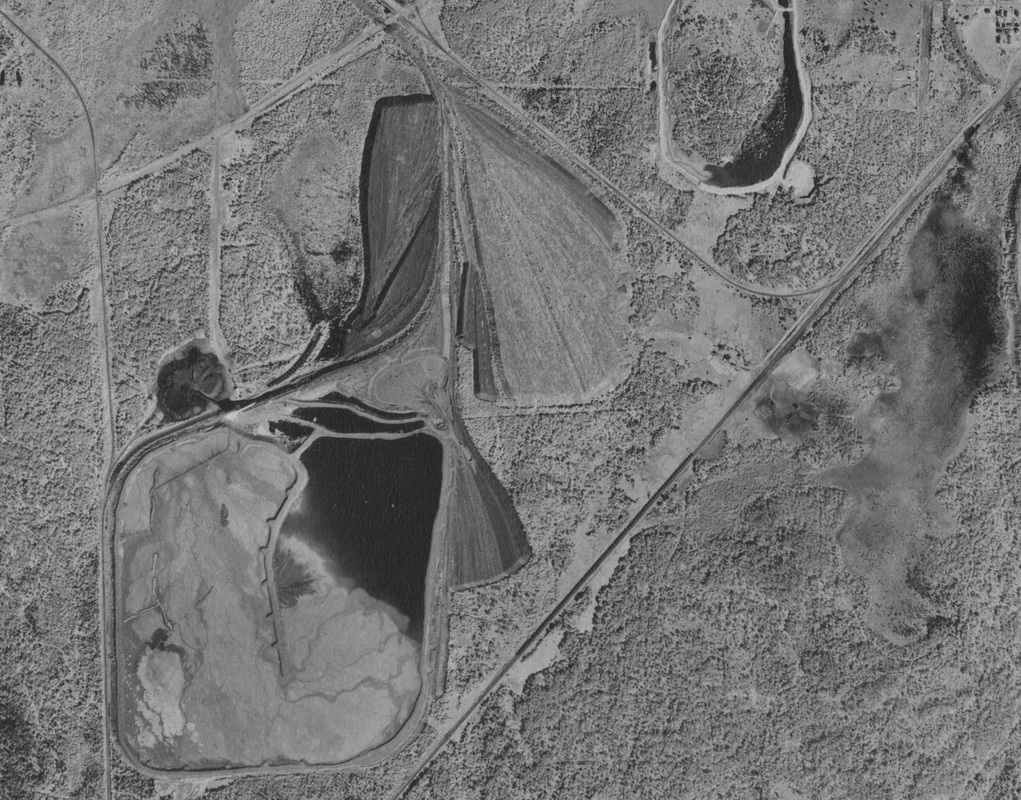

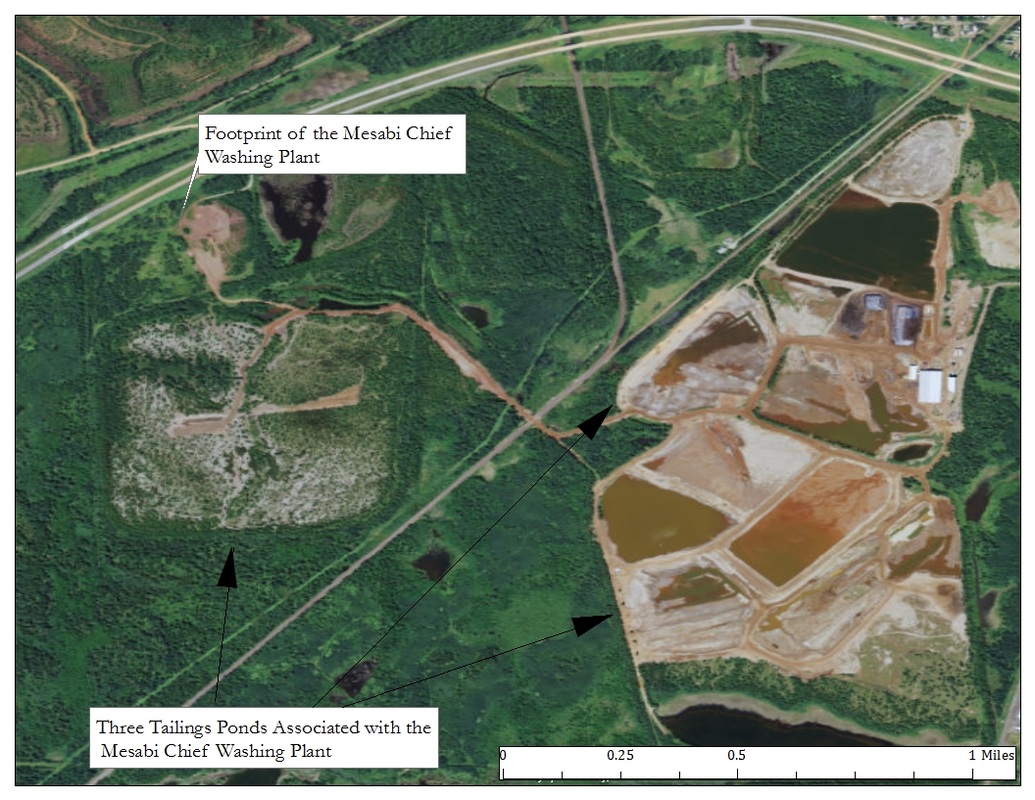

"This installation will do more than the old type of installation did, and at less cost..." -Earl Hunner, "Recent Developments in Open-pit Mining on the Mesabi Range" Keewatin, MN is located at the far eastern extent of Itasca County, at the juncture of Itasca and St. Louis Counties in Northern Minnesota. The Mesabi Range is bifurcated politically, but also geologically, as the western end of the Mesabi, those ore bodies within Itasca County, tend to be heavy in silica and light in iron, and were known historically as western Mesabi washable ore. During the 1929-1930 mining season, the M.A. Hanna Co. began stripping the overburden encasing its new Mesabi Chief Mine, located just west of Keewatin, and drawing plans for the construction of a washing plant located south of the mine itself. "The proposed pit area, roughly rectangular in shape, contains about 75 acres. The surface overburden averages about 30 to 40 ft. deep. Underlying this are four alternating layers of merchantable ore and paint rock, each averaging 10 to 15 ft. thick, and overlying wash ore material about 40 ft. thick." - (Earl E. Hunner, "Some Recent Developments in Open-pit Mining on the Mesabi Range", in AIME Transactions, No. 38, Technical Publication No. 333, pp. 8). "To produce the wash ore concentrates, a new type of screening plant and an improved washing plant have been built, with a capacity up to 380 tons crude per hour, or about 300,00 tons concentrates, single shift, per season." - (Earl E. Hunner, "Some Recent Developments in Open-pit Mining on the Mesabi Range", in AIME Transactions, No. 38, Technical Publication No. 333, pp. 8). Constructed in 1929, the Mesabi Chief washing plant had an initial treatment capacity of roughly 400 tons of low-grade ore per hour. The initial shipments of ore processed at the plant came chiefly from the newly electrified Mesabi Chief Mine (A.J. Hain, "Iron Ore", in Iron Trade Review, January 2, 1930, pp. 35). Not all the ore coming from the Mesabi Chief was low-grade ore, about half of the product extracted in the early years was graded as direct shipping ore, and was not treated by the washing plant. The M.A. Hanna Co contracted the construction of the Mesabi Chief washing plant to the Link Belt Co. (a notable name within mining sites of the early 20th century) who designed the handling of the ore from mine to plant. The beneficiation process at the Mesabi Chief entailed both screening the material at the mine and washing the ore at the plant. After screening, which classified the ore into oversized and undersized material, the finer, undersized material traveled up a covered belt conveyor to the washing plant, where it was reclassified, crushed, and concentrated. During its operation, the Mesabi Chief washing plant employed a handful of innovate technologies not found in other washing plants of the Range, including a large elevated concentrate stacker and Dorr bowl classifiers, which classified the ore rather than the traditional log washers used in other plants within the Mesabi. The most pronounced features of the Mesabi Chief washing plant was the structural steel ore stacker that lifted concentrates from the plant up a conveying belt to be stockpiled outside the facility. The ore stacker had a stacking capacity of 100,000 tons of concentrate, requiring a surface radius of 165 feet with a 40 foot reach to the top of the pile (S.A. Mahon, "Iron Ore Stacker at the Mesabi Chief Mine", in Mining & Metallurgy, August 1935, pp. 334-335). In addition to processing ore from its namesake mine, the Mesabi Chief Washing Plant treated ore from the nearby Aromac, Bray, Carlz No. 2, Gordon, Gordon Annex, Mississippi Group, and Stein mines. The Mesabi Chief was the flagship mine of the M.A. Hanna Company in the Keewatin area. Active from 1929 to 1966 (the mine did have a small shipment in 1913), the Mesabi Chief mine shipped more than 10 million tons of low-grade iron ore. In order to process all of this ore, the Mesabi Chief, and other washing plants required a great deal of water, roughly 900 gallons of water for each ton of iron ore concentrate processed. Of the 33 known beneficiation plants in Itasca County, only one, the Butler Taconite plant in Nashwauk, was developed to process and pelletize taconite. On the other hand, in St. Louis County there are 54 known beneficiation plants, and 10 taconite pelletizing plants. This is an important statistic to keep in mind, when comparing the contemporary landscapes of the two counties. Taconite, too, is a low grade iron ore, lower in grade than even the washable ores of the western Mesabi. Similar to the washable ores of the western Mesabi, taconite needed to be processed before it could be fed to a blast furnace, through steps such as crushing, washing and concentrating (through magnetism). However, due to its fineness, the processed taconite needed to be amalgamated through a process called pelletization, which tumbled the fine grained concentrate in a mixture of water and clay to produce taconite pellets. These pellets, and their physical uniformity, were the product of a unique envirotechnical system - one whose ability to produce a standardized product acted as a boon to the mines of St. Louis County, but also pushed many of the mines and beneficiation plants in Itasca County into relative obscurity. The Mesabi Chief is one of the many ghost plants in the Mesabi Range that ultimately succumbed to the political and industrial fanfare of taconite. Although the Mesabi Chief washing plant and its impressive ore stacker have been absent from the industrial landscape of eastern Itasca County for at least three decades, its environmental legacy remains - found in the linear cuts of rail lines, the subtle footprints of the plant, and the tailings basins - whose distinct elevated embankments may too, soon become obfuscated by an evolving envirotechnical system. Just south of Highway 169, the three tailings basins created by the Mesabi Chief are the most visible, yet silent reminders of this ghost plant's industrial past, and as happens with much mine waste, the tailings of the Mesabi Chief are being reworked by new mining interests with new technologies, extracting a profit from yesterdays waste.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorJohn Baeten holds a PhD in Industrial Heritage and Archaeology from Michigan Technological University. His research aims to contextualize the environmental legacies of industrialization as meaningful cultural heritage. Archives

May 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed