|

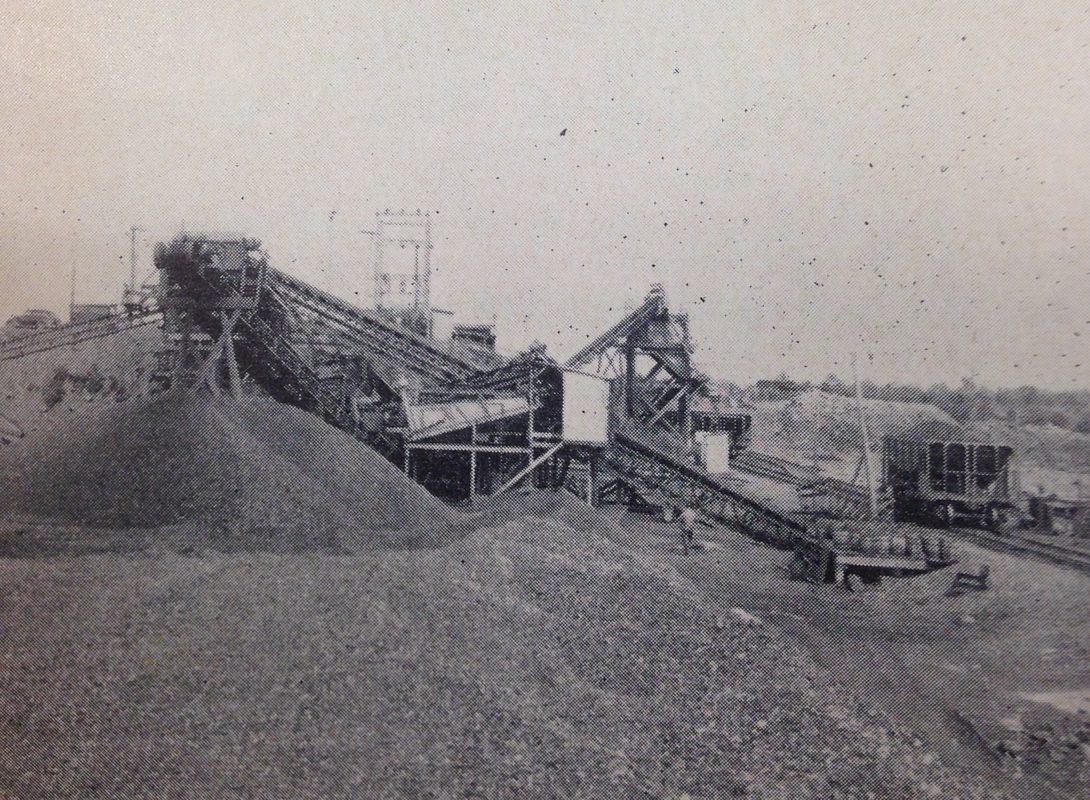

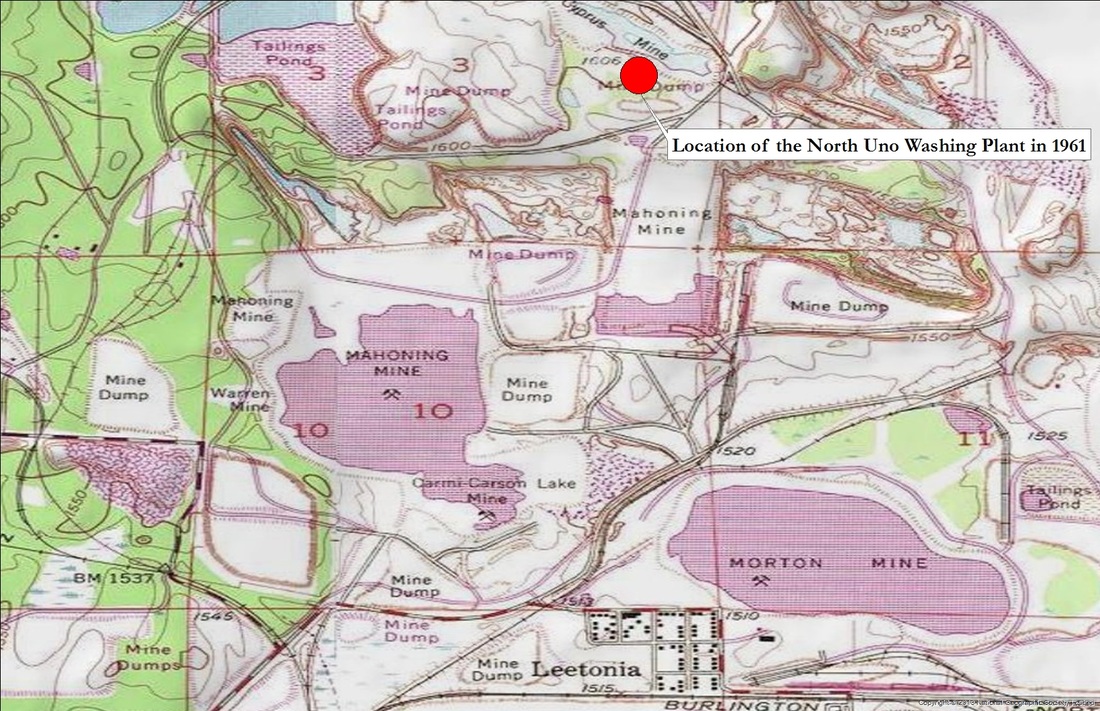

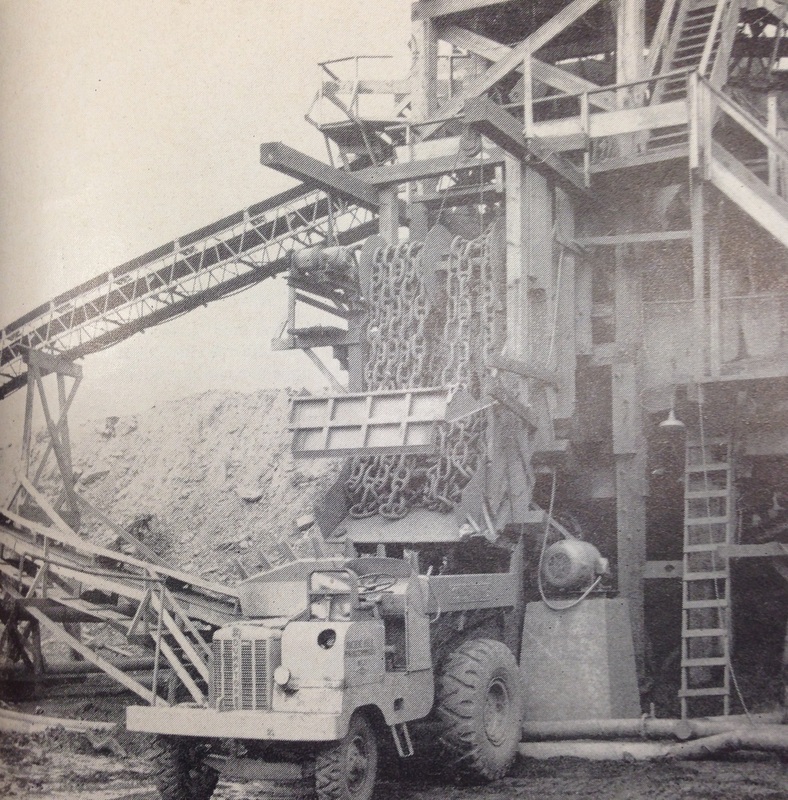

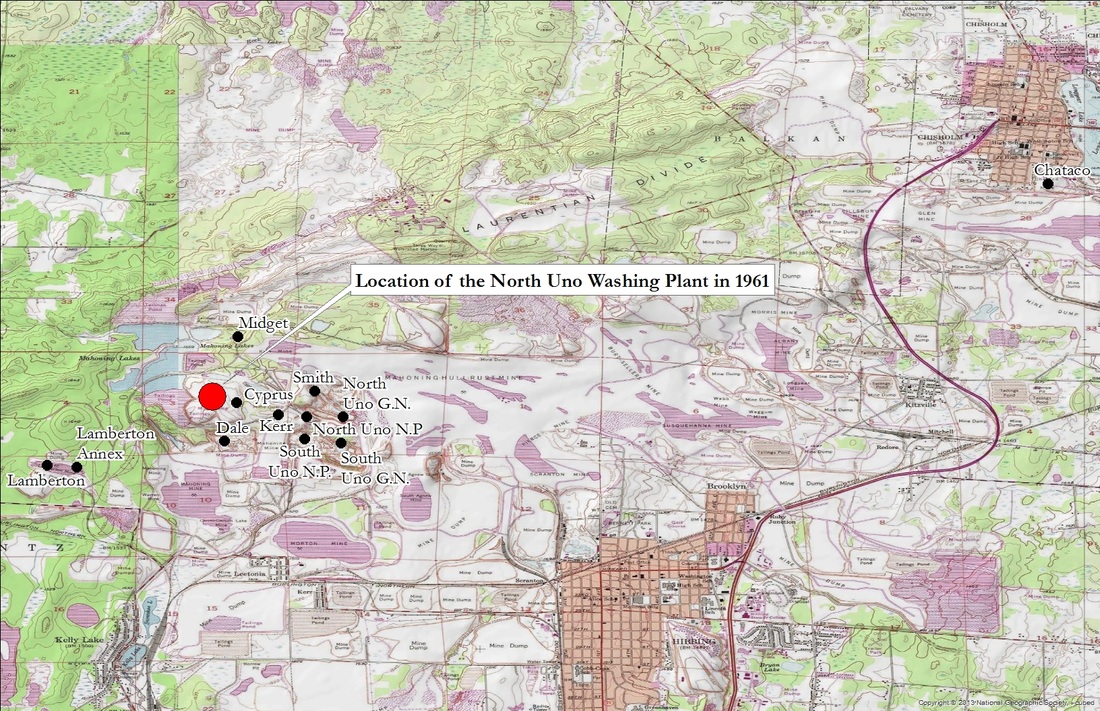

"The North Uno washing plant, built with an eye to moving when the ore is exhausted, does a good job on the ore from the mine." -E.S. Tillinghast, Mining World, 1948. The historic mining community of Leetonia, MN is located in the eastern section of the Mesabi Iron Range, roughly 3 miles west of Hibbing, MN and 1 mile south of the massive Hull-Rust-Mahoning Pit. Shaped like an upside down "L", the community of Leetonia is laid out in an orderly grid with five streets running north-south, and five streets running east-west. The streets running north-south follow a numerical naming convention, while the names of the east-west streets bear the names of former mines, such as Morton, Dale, and Kerr - unintentional memorials to a handful of ghost mines consumed by the nation's growing demand for taconite. Both the Dale and the Kerr produced low-grade washable ore, material that was treated for a handful of years at one of the more notable mobile beneficiation plants in the Mesabi, the North Uno washing plant. Incorporated in 1946, the Pacific Isle Mining Co. was one of a handful of mid-sized mining companies that worked the incongruous tracts of low-grade ores in the Mesabi Range, which spread from Virginia,MN to just west of Hibbing. By 1948, Pacific Isle was operating four open pit mines in the Eastern Mesabi along with conducting reclamation efforts at a handful of the lean ore dumps that were found scattered next to many of the exhausted direct shipping ore mines. All of this low-grade ore needed to be beneficiated, and as we saw in the last post on the Coons-Pacific Concentrator, the Pacific Isle Mining Co. decided that the most economical way to treat this ore was through custom milling - and the North Uno washing plant acted as a custom mill, treating a variety of low-grade ores within the eastern Mesabi Range. A custom mill is a processing facility that treats diverse ores, meaning that its flow sheet has built in flexibility, rather than those mills that were tailored to only process ore from an individual mine. Custom Milling allowed smaller mines and mining companies, such as Pacific Isle, the ability to process ore at a single facility, rather than expending additional resources in constructing and operating individual beneficiation plants. The North Uno also featured a savvy technological innovation - it was mobile - designed with the flexibility to move to a new orebody when an older one became exhausted. "That Pacific Isle is not exactly a bonanza is apparent. However, it seems to be producing a modest, but satisfactory, financial return to its owners. Beyond that, it is producing a merchantable iron concentrate from material of no current value to other types of operations. Thus, the nation's resources are being extended, and the way is being pioneered for others to convert to usable form material now being by-passsed or piled on waste dumps." ("Pacific Isle's North Uno Mill Upgrades Varied Iron Ores", in Mining World, June, 1950, pp.15) The North Uno plant was a pre-fabricated "Wemco Mobil-Mill" designed by the Western Machinery Co. of San Francisco, CA. Erected first in Michigan, then disassembled and freighted to Leetonia, the North Uno washing plant started processing low-grade ores at the tail end of the 1948 mining season. Originally designed with a capacity of up to 35 tons per hour, by the end of its first season, the North Uno was upgraded to a capacity of 100 tons an hour by doubling the washing and magnetic sections. ("Pacific Isle's North Uno Mill Upgrades Varied Iron Ores", in Mining World, June 1950, pp. 12) During its operation the North Uno Plant treated ores from a number of mines, including the North and South Uno (both N.P. and G.N.), the Chataco, the Cyprus and Cyprus-Rust, Dale, Kerr, the Lamberton and Lamberton Annex, the Midget, Shada, and the Smith. The ores from these mines were of variable constitutions, meaning that each ore required a slightly differently treatment from the next. Although the North Uno was a relatively small washing plant, it had a mighty thirst. During its first year of operation the plant consumed upwards of 2,500 gallons of water a minute, due in part to the ore of the North Uno Mine having a paint-rock consistency. (E.S. Tillinghast, Mining World, July 1948, pp. 28) Most low-grade washing plants required around 900 gallons of water per minute to process ore, which helped remove the high quantity of silica from the sandy washable iron ore. Paint-rock ores were treated much like taconite for the first 40 years of open pit mining in the Mesabi Range, seen as having such small value that they were considered to be waste more so than they were thought of as orebodies. From a 1919 report detailing paint rock: "Certain fee owners and the State officials have been inclined to insist that this material (paint rock) is an ore. The mine owners insist that it is not. The writer agrees with the mine owners. "The mine owners refuse to ship this material, but in open-pit mining an easy compromise of the matter is possible, because paint rock has to be removed from the pits, anyway, and can be dumped on a stock pile near the mine to await indefinitely the possibility of its becoming merchantable." (J.R. Finlay, "Method of Administrating Leases of Iron-Ore Deposits Belonging to the State of Minnesota", Bureau of Mines Technical Paper 222, 1919, pp. 33). "The plant was built for a temporary job and contains no "frills", but it serves the purpose well and can easily be moved to another location when necessary." -E.S. Tillinghast, Mining World, July 1948, pp. 27. Once in the plant, the ore was crushed and screened much like the process employed at the Coons-Pacific, and as the classified material made its way further through the North Uno's flow sheet, it was subjected to spiral concentrating and a heavy-media section. Roughly half of the material that entered the North Uno plant was eventually treated by the heavy-media section, which employed Hardinge Separators - machines that resembled ball mills that helped concentrate the slurry of iron fines away from the gangue material. ("Pacific Isle's North Uno Mill Upgrades Varied Iron Ores", in Mining World, June, 1950, pp.15) The material that passed through the HMS was further treated by magnetic separation, a spiral section and a hydroseparator - with waste material accumulating in three distinct areas. The large scalped barren chucks of gangue removed at the receiving bin were hauled by trucks (see image above) to waste rock piles. Coarse tailings were sent to a coarse tailings pile, while fine tailings were pumped and deposited into a tailings pond. ("Pacific Isle's North Uno Mill Upgrades Varied Iron Ores", in Mining World, June, 1950, pp.13-14). By 1950, the North Uno washing plant had doubled its processing capacity and expanded its technological infrastructure, adding a "circuit of Humphrey's spirals for the treatment of fines". (Mining World, 1950, Mine Development and Directory, pp. 56C). The expansion of the North Uno washing plant represents the industrial optimism of the Pacific Isle Mining Co., symbolic of many mining companies in the Mesabi who continued to invest, expand, and refine their beneficiation plants in an attempt to elevate the quantity of iron in their concentrates. The 1950s saw the eastern Mesabi transform into a landscape dominated by taconite mining, and the activities of the North Uno washing plant and Pacific Isle began to garner less attention in the press than the sprawling taconite mines. Pacific Isle seems to have retained controlling interest in the majority of the mines listed above up to 1957, when mining production appears to stop at all of the mines with the exception of the North Uno. The North Uno mine, and likely the North Uno washing plant were transferred to the M.A. Hanna Mining Co. soon after, and Pacific Isle soon became a producer of the past. In 1963 the M.A. Hanna Mining Co. deemed the ore body exhausted and closed the mine - leaving the North Uno washing plant as another redundant technology on the landscape. My assumption is that the washing plant was likely scrapped soon after 1963 - though I've yet to uncover what happened to any of the physical technologies within the ghost plants of the Lake Superior Iron District. This is a video I shot of the Hull-Rust open pit mine at Hibbing, MN. The expansion of this mine, and the increasing role of taconite led to the eventual closure and abandonment of the North Uno washing plant. Unlike the other ghost plants covered in this blog, the North Uno's industrial legacy is embedded with ephemerality - reflected in the plant's mobile character along with its lack of a superstructure to house the washing plant's functioning technologies. The plant also operated for a relatively short time span - less than 15 years - never truly reaching industrial maturity, nor producing the visible environmental legacies we've become accustom to seeing in many of the other ghost plants, such as the Hunner or Trout Lake Concentrator.

By 1961, the massive Mahoning open pit mine was already encroaching on the North Uno, digging away at the plant's rapidly shrinking foothold atop a small swath of taconite. Today, nothing remains of the North Uno plant. As you can see in the video and image above, the consolidation of the Hull, Rust, and Mahoning mines have devoured an industrial landscape - reclaiming the landscapes of the Leetonia, Kerr, Dale, Cyprus and Midget mines and sentencing the North Uno washing plant to death by redundancy. But, the Hull-Rust-Mahoning mine has produced an entirely new mining landscape, one that features massive industrial benches and taconite terraces, emblematic of the physical, social and environmental transitions in the industrial heritage.

1 Comment

|

AuthorJohn Baeten holds a PhD in Industrial Heritage and Archaeology from Michigan Technological University. His research aims to contextualize the environmental legacies of industrialization as meaningful cultural heritage. Archives

May 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed