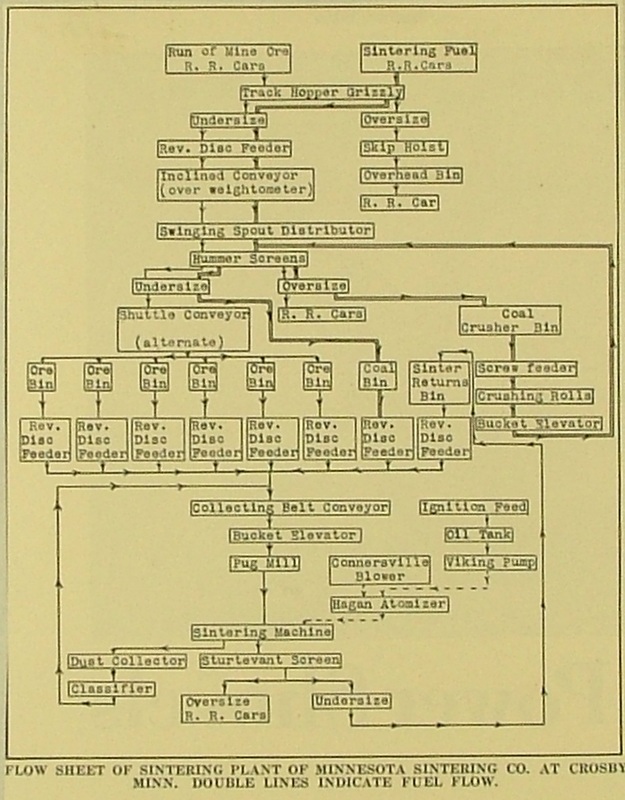

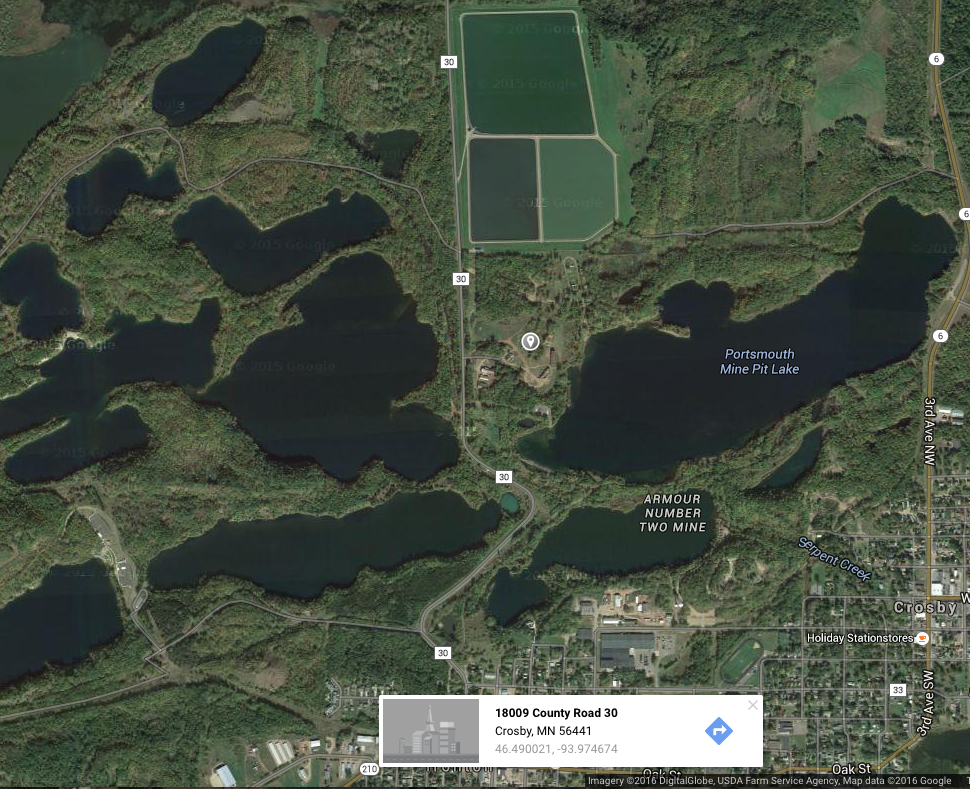

The Portsmouth Sintering Plant 1924-1966 - Fred Sutherland "Almost everything is a dull rusty red. This is the color of the railroad ties, of the soil, of the stockpiles, and even the buildings of the mines. The landscape has a blasted and forlorn look, even though most of the mines are operating, somehow (it) always seems lifeless and desolate." - George F. Brighten, 1941 I'm pleased to feature a guest post detailing a ghost plant in the Cuyuna Range of Minnesota, written by my colleague Fred Sutherland, a recent graduate from the Industrial Heritage and Archaeology Program at Michigan Tech. Fred's dissertation, "The Cuyuna Iron Range: Legacy Of A 20th-Century Industrial Community" explores the industrial history of the Cuyuna Range, through the lens of Industrial Archaeology. Enjoy JB! At a site about 100 miles south of the Mesabi Iron Range on the Cuyuna Iron Range an unusual ore refinement process was conducted during the mid-20th century. It was unusual because it was the only example of its type in the Great Lakes region and also for its scale, as the largest of its kind in the United States while it was in operation. The Portsmouth Sintering Plant operated for 42 years, even for 8 years after its local mine closed, because it processed the unmarketable portion of fine-grained iron ores found across the Cuyuna Range into a marketable product called sinter. Sintering mixes small iron ore particles with coal fines and then heats the mixture to the point the iron fuses together into larger clumps. Portsmouth Sinter became what one writer called a “cracker jack man-made ore” that was “a well known trade name” throughout the iron industry of the time[1]. Reports from this site show its daily production grew over time from around 800 tons in 1925 to nearly 1700 tons by 1950 as the machinery and management of resources were improved. In 1944, the output of this sintering plant was estimated to contribute 204,000 tons or 34% of the 589,000 tons of annual output from its mine location. This process of excavating, transporting, and heating fine grained ores created a significant amount of dust which had a noticeable impact across the region. George F. Brightman, an economic geographer, gave a fascinating description of the height of mining in the Cuyuna Rage during World War II. Shortly after describing the massive tailings piles connected by radiating “ribs” of railroad lines to benefaction plants, he then describes the incredible amount of dust present everywhere he went. He said:“Almost everything is a dull rusty red. This is the color of the railroad ties, of the soil, of the stockpiles, and even the buildings of the mines. The landscape has a blasted and forlorn look, even though most of the mines are operating, somehow always seems lifeless and desolate”[2]. Residents that lived through this era in the mid-20th century told me they could not leave clothes out to dry on certain days because it would become covered in red dust if the wind blew from the wrong direction. Other references to the air quality near this plant were not recorded in documents I have been able to find, but must have certainly been an issue in the daily life of mine workers and their families. A current issue involving the fine grained materials from former mines is protecting water quality. This fine grained iron rich material erodes easily, causing significant shoreline loss and water contamination issues around former mine pit lakes. Efforts at planting and managing trees along these shores is an ongoing challenge [3]. “Portsmouth Sintering Plant is operating at a high rate and is steadily sending out loaded railroad cars to the ore docks. The plant is a lone operation of its kind and favors sintering ore at the source instead of sintering at the point of consumption -a controversy held in abeyance for years. Portsmouth Sinter is a well known trade name noted for its excellent structure, high iron content, and low moisture. Its crunchy appearance might lead to its being called the ‘cracker jack man-made ore’ of the Cuyuna Range.” Skillings' Mining Review, 1951 The ruins of this sintering plant remain on private property, but there is a public walking trail crossing County Route 30 north of Crosby that goes within eyesight of the concrete remains. The ruins are listed on the National Register of Historic Places, incorrectly, as the ‘Ironton Sintering Plant’[4]. The site is within the municipal bounds of the City of Crosby and it was only called the Evergreen or Portsmouth Sintering Plant while it was in operation. The legacy of this site is that it was an important facilitator of regional iron production, even after its local mine closed. It was also an outlier for its size and approach to refining iron ore in the Great Lakes Mining District. The environmental legacy appears to be tied to the fragile shorelines and bodies of water around the remnants of the open pit mines the sintering plant helped to sustain in the 20th century. Notes:

[1] “Use All Known Ore Processing Methods Here” Crosby-Ironton Courier. September 6th, 1951. Pages 1 and 5. [2] Brightman, George F. “Cuyuna Iron Range”. Economic Geography 18(3), July 1942. 275-286 [3] Perkins, Chelsey. “Crow Wing County: More than a million - Revenue surplus a measure of economic recovery” Brainerd Dispatch. February 23, 2016. http://www.brainerddispatch.com/news/3954590-crow-wing-county-more-million-revenue-surplus-measure-economic-recovery [4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ironton_Sintering_Plant_Complex

3 Comments

Alfredo Petrov

10/3/2017 04:59:29

Very interesting article; thanks! I came across it accidentally while attempting to find out information about a sample of rutile crystals (titanium dioxide) that is labelled as having been synthesized in Crosby, Minnesota. Do you happen to know whether this iron ore sintering plant ever produced any titanium as a byproduct, or experimented with titanium production? I can't think of where else in Crosby it could have come from if not this plant.

Reply

John Baeten

10/4/2017 09:09:42

Hi Alfredo - and thanks for the comment! I am not sure of the titanium question - I'd recommend you contact Fred Sutherland, who was the guest author for this post.

Reply

Fred Sutherland

10/11/2017 11:24:56

Hi Alfredo, sorry for the delay in my reply to you. I do not think this particular sintering plant made anything but sintered iron. I do believe that this product may have been made in the neighboring town of Riverton where there was a plant that refined manganese and other metals (perhaps titanium) from the local ores. They had a lot of government funding to develop new metal refining processes related to battery technology. Could this titanium sample be related to batteries? my 30-second Wikipedia search notes that rutile titanium dioxide is used in Li-ion and Na-ion battery technology: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Titanium_dioxide#Other_applications

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorJohn Baeten holds a PhD in Industrial Heritage and Archaeology from Michigan Technological University. His research aims to contextualize the environmental legacies of industrialization as meaningful cultural heritage. Archives

May 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed