|

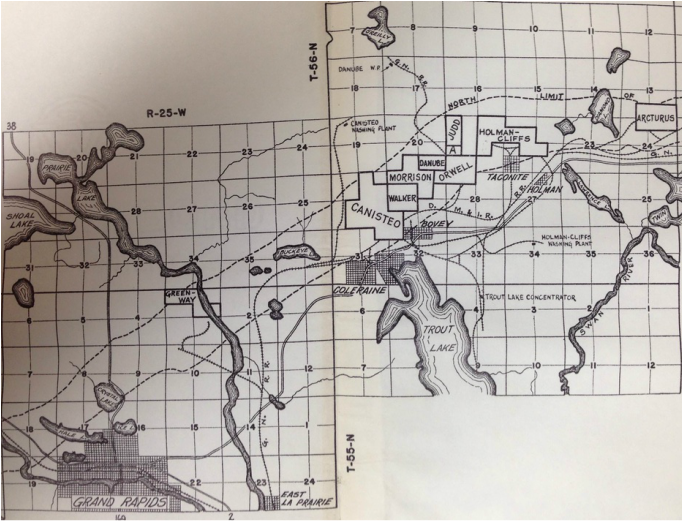

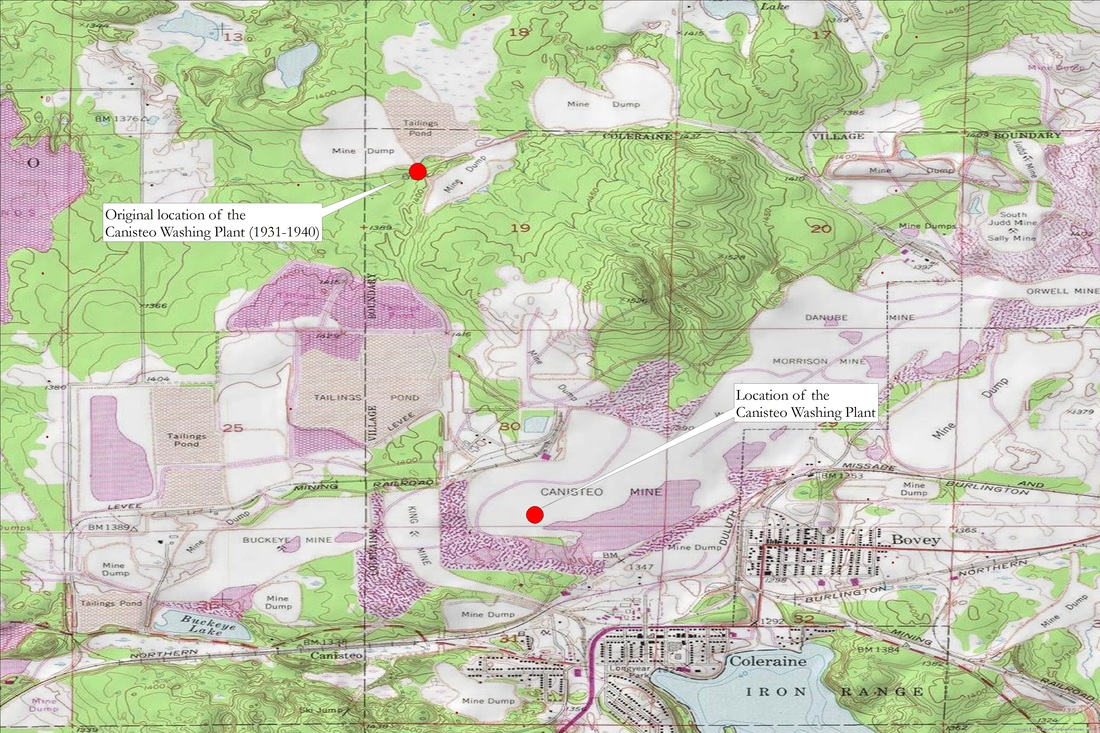

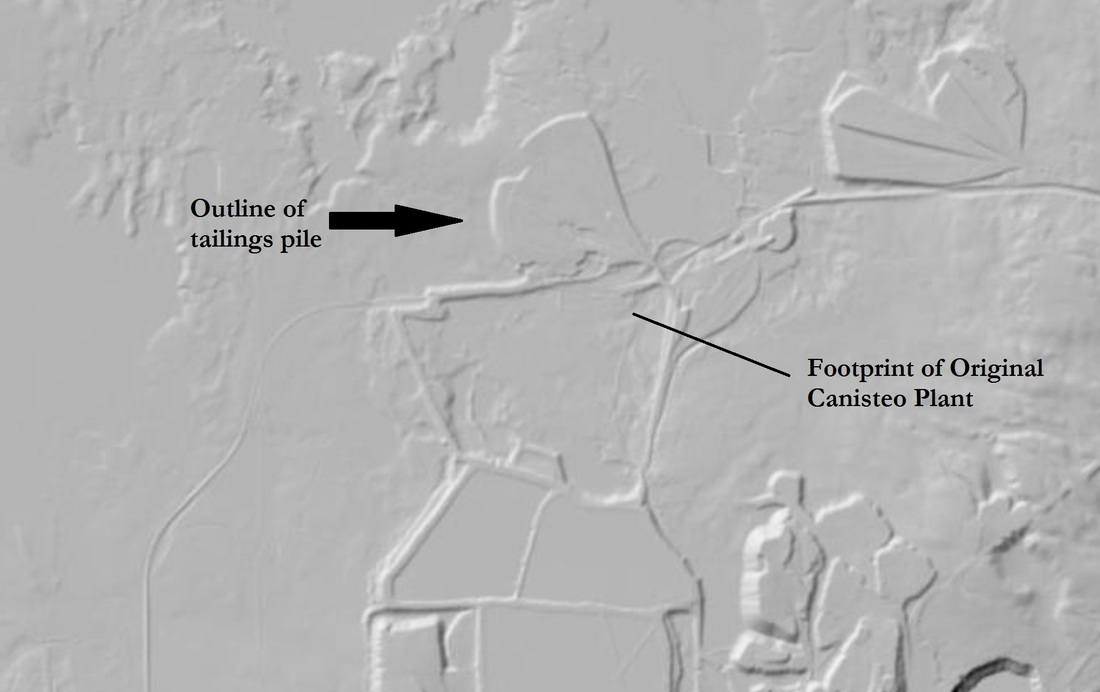

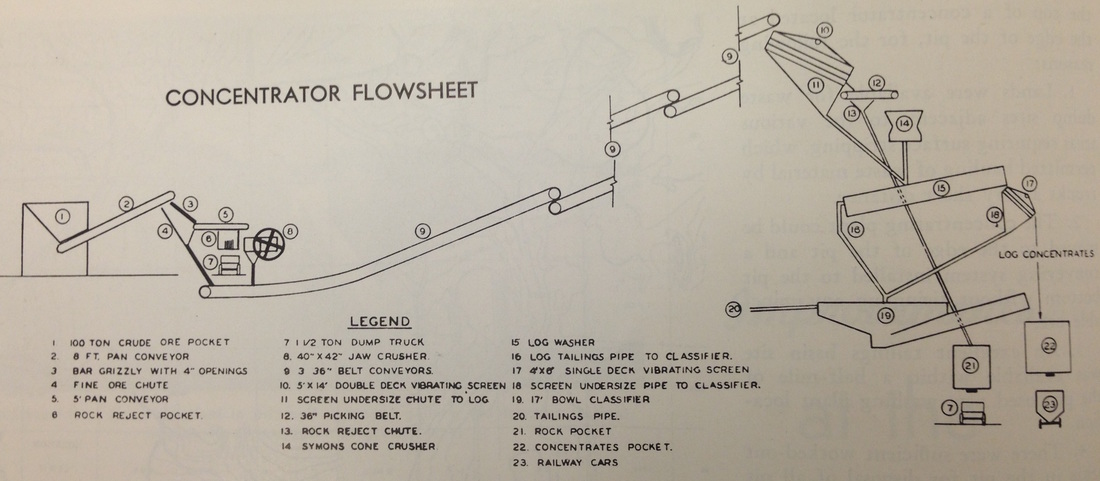

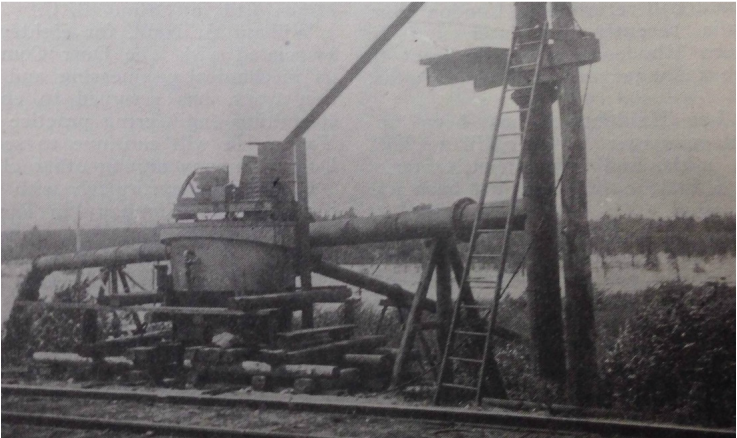

"Canisteo iron ore concentrate is a well-known trade name in many of the large steel plants of the East, as it is the Canisteo mine which pioneered concentration of iron ore on the Mesabi iron range on a commercial scale." Skillings' Mining Review, Vol. 29, No. 28, Nov. 2, 1940 The historic Canisteo mining district lies within the far western end of the Mesabi, running a length of nearly 10 miles beginning near Grand Rapids and moving northeast towards the town of Holman. I've covered this region in two other posts - the first on the Trout Lake Concentrator, and another on the Hunner Concentrating Plant. The Canisteo District was home to 10 beneficiation plants which operated for nearly 70 years, from 1907 to the early 1980s. All of these facilities now exist as ghosts on the landscape, visibly absent yet environmentally persistent. The former location of the Canisteo Washing Plant is submerged within the flooded cavity of the Canisteo Mine, where largemouth and smallmouth bass, northern pike, bluegill and cisco now swim over the roadbeds where 15-ton dump trucks used to busily transport ore from mine to mill. The history of many mines in the Lake Superior Iron District are both convoluted and fragmented - with mine owners often leasing mining property to mine operators who in turn might then contract out to smaller mining companies, creating a headache for contemporary researchers. The Canisteo's history is equally fractured and confusing. The Oliver Iron Mining Co. (OIMC) opened the Canisteo Mine in 1906, but leased the mine to the Canisteo Mining Co., who operated it until 1925 when all of the direct shipping ore within the Canisteo ore body had become exhausted, and the OIMC was left with a surplus of sandy, low-grade ore. "Foremost in importance is the fact that in mines on the western end of the Mesabi range the percentage of silica has become abnormally high. This probably affects 100,000,000 tons of ore, hitherto considered merchantable as mined, or practically so. Attention was directed pointedly to the matter when the Oliver Iron Mining Co. canceled the lease of the Canisteo mine, because the company was unable to remove the excess silica by the usual washing process." A.J. Hain, "New Era in Iron Ore Industry; Trade Outlook Bright", in Iron Trade, January 1, 1925, pp. 38. That same year, 1925, OIMC sold the mine to the Canisteo Mining Co., who left the mine idle for the next five years until it again changed ownership, this time to the Mesaba-Cliffs Mining Co., who constructed the Canisteo Washing Plant, and operated the mine until 1938, when the mine was eventually sold to the more formidable Cleveland Cliffs Mining Co. Constructed during the 1929-1930 season, and placed into operation in 1931, the Canisteo Washing Plant was the Mesabi's 44th beneficiation plant, and also one of the largest in the Lake Superior District, with a capacity of nearly 700,000 tons of concentrates per year. Prior to building its washing plant, the Canisteo mine sent its washable ore to the nearby Trout Lake Concentrator at Coleraine, the flagship plant of the Oliver Iron Mining Co. "Could this worthless iron ore be made available for the furnaces, could the western Mesaba be subjected to the same tremendous development that had been carried on along other parts of the range, what an opportunity for effort, what a vision for the enthusiast!" - Dwight E. Woodbridge ("Concentrating the Lean Ores of the Mesaba Range", in The Iron Age, Jan. 6, 1910, pp. 48). During the tail end of the 1930 season, Cleveland Cliffs pumped more than 2 billion gallons of water from the open pit Canisteo Mine - which due to a series of ownership changes - had been left idle for a period of 5 years - allowing ground water to slowly seep into the mine workings. When the pumps in an open pit mine cease to rid the mine workings of water, a rapid landscape transition begins, turning a "good mine" into a lake, which has happened to the Canisteo more than once. During the 1940 season, the Canisteo plant was moved from its northern location to the north edge of the Canisteo pit. Moving the plant was undertaken by the Worden-Allen Co. (a Milwaukee-based company that specialized in structural steel) which required dismantling the large plant -- no easy task --, as the Canisteo Plant was one of the biggest concentrators in the Mesabi - and then re-erecting it (Skillings' Mining Review, Vol. 29, No. 28, pp. 1). Little information remains detailing the activity of the Canisteo Washing Plant at its historical location - but, what we can discern is that it operated there for a little less than a decade and produced a visible tailings pile which was discharged to the northwest of the plant (see the LIDAR image below). The reasons for moving the plant closer to the mine might seem obvious - the cost of transporting the ore would be much cheaper with the washing plant next to the mine - but the reasoning behind the move were a little more complex. In addition to extracting and concentrating ore, all mines and beneficiation plants produce waste - and figuring out where to put this waste was a reoccurring theme for mining engineers and mine owners. The new location next to the Canisteo pit had an ample amount of land available near the mine for disposing of overburden, as well as "An excellent tailings basin site was available within a half-mile of the proposed new washing plant location." W.A. Sterling, "Improvements at the Canisteo Mine", in Mining Congress Journal, May, 1941, pp. 12-13 While the plant retained its original flow sheet after the move, the operation within the mine changed drastically -mainly in how the ore was transported from the mine to the washing plant. Within the mine, the 15 miles of railway (this number probably takes into effect the distance of the former location of the plant) that once hauled ore from the mine to the washing plant was removed and replaced with 50 ft. wide roadbeds for dump trucks. Trucks made the transportation of ore from mine to the plant more economically efficient and divorced the mine from its dependence on costly steam powered equipment at the dawn of the diesel era. In addition to the use of trucks as primary movers, the Canisteo Washing Plant employed a revamped conveying system which sent the ore from the base of the bit to the top of the plant, described below: "A 1,000 ft. long belt conveyor system operating on an 18-degree slope from storage pocket in pit to top of concentrator building, has replaced railroad car transportation. "This inclined conveyor is made up of three sections each 340-ft. centers, using 36-inch wide belt at 500 feet per minute for a capacity of 750 tons per hour minus 4-inch ore." W.E. Philips, "Belt Conveyors in Metal Mining", in Mining Congress Journal, Vol. 28, June 1942, pp. 25-26). Once at the conveyor - "Over 4-inch material passes to another apron where it is handpicked and discharged to the primary crusher and then deposited upon the protective layer of finer ore already on the belt, where it travels upward over three conveyor sections to the concentrator, one of the largest on the Mesabi range with a rated capacity of about 700,000 tons of iron ore concentrates per season." W.E. Philips, "Belt Conveyors in Metal Mining", in Mining Congress Journal, Vol. 28, June 1942, pp.72). The tailings from the washing plant were laundered through an 800 ft. - 16 in. pipe into a hydro pump, which sent them next into a 1700 ft. - 12 in. pipe that funneled them into the tailings basin roughly 1/2 mile west northwest from the Canisteo Washing Plant. The tailings basin was massive (see image below) and was reinforced with an earthen dike constructed with 15 ft. walls that measured 18 ft. width at their top. (W.A. Sterling, "Improvements and the Canisteo Mine", in Mining Congress, May, 1941, pp. 13) All beneficiation plants, including the Canisteo Washing Plant, required a complex hydraulic infrastructure in order to bring water to the plant to wash the low-grade ore entering the facility, as well as to launder the waste away from the plant to the tailings basin. At the Canisteo plant, this was accomplished through the development of a clean water reservoir next to the mill (see aerial image above). The reservoir had a 10,000,000 gallon capacity and was fed from the dewatering pumps within the Canisteo mine. Since the reservoir was located below the mill, a system of gravity pumps were installed that transported the water from the reservoir to the ground floor of the washing plant. During the 1961 season, Cleveland Cliffs began constructing an additional cyclone plant adjacent to the main washing plant, representative of the company's continued faith in the low-grade washable deposits of the Coleraine region. (Skillings Mining Review, Vol. 50, No. 11, March 18, 1961, pp. 5) The plant apparently continued to operate smoothly into the 1970s, and in 1974, Cleveland Cliffs' modified the flow sheet of the plant, adding cyclone, spiral and heavy media concentration units to the facility which were operated on a "17-shift per week schedule" (Skillings' Mining Review, June 1974, pp. 19.). However, the benefits of this innovation were short lived - and like most other non-taconite mines in the Mesabi, the Canisteo was on its last leg. The Canisteo Mine and the Canisteo Washing Plant were closed in 1981, with Cleveland Cliffs deeming that the mine had "reached the end of its economic life." At the time of their closure,roughly 200 workers were employed at the Canisteo operation, which extracted more than 50 million tons of sandy ores during its lifetime (Skillings' Mining Review, June 20, 1981, pp. 5.). The very mine that once fed ore to the Canisteo Washing Plant now serves as the ghost plant's watery grave, an ironic resting place for one of the largest, longest running, and technologically savvy washing plants in the Western Mesabi.

Comments are closed.

|

AuthorJohn Baeten holds a PhD in Industrial Heritage and Archaeology from Michigan Technological University. His research aims to contextualize the environmental legacies of industrialization as meaningful cultural heritage. Archives

May 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed