|

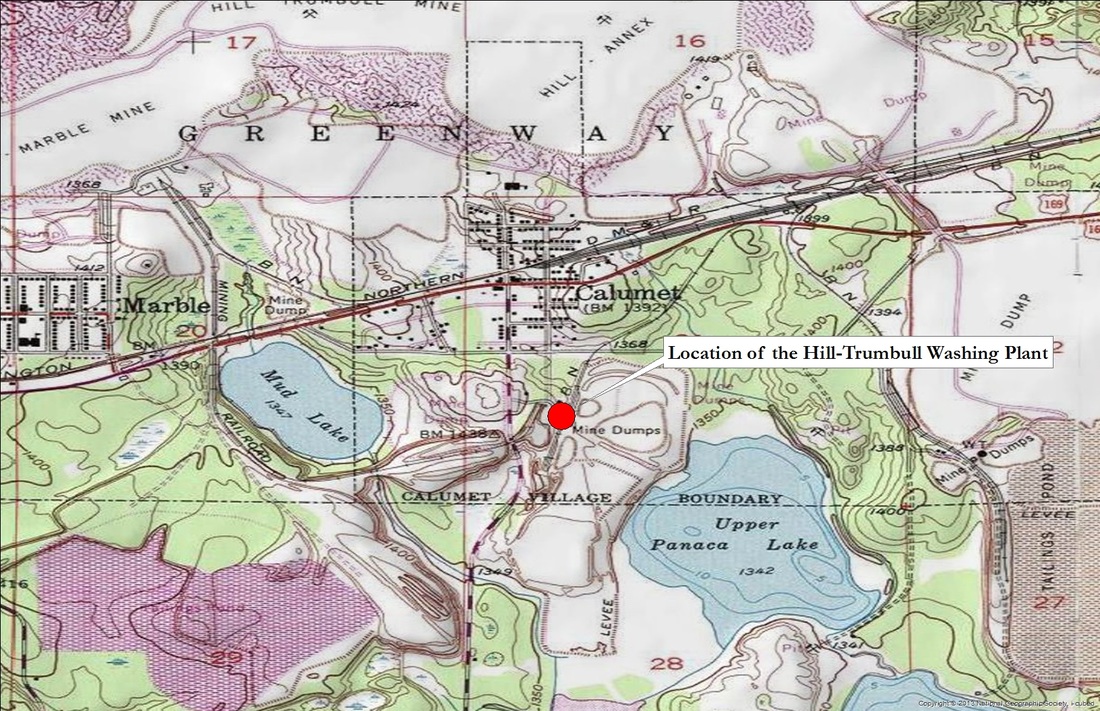

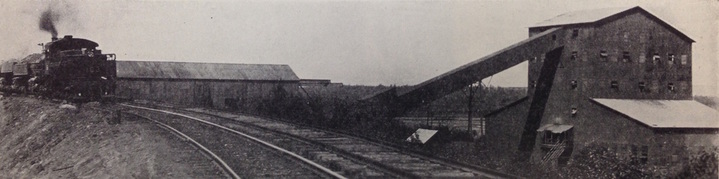

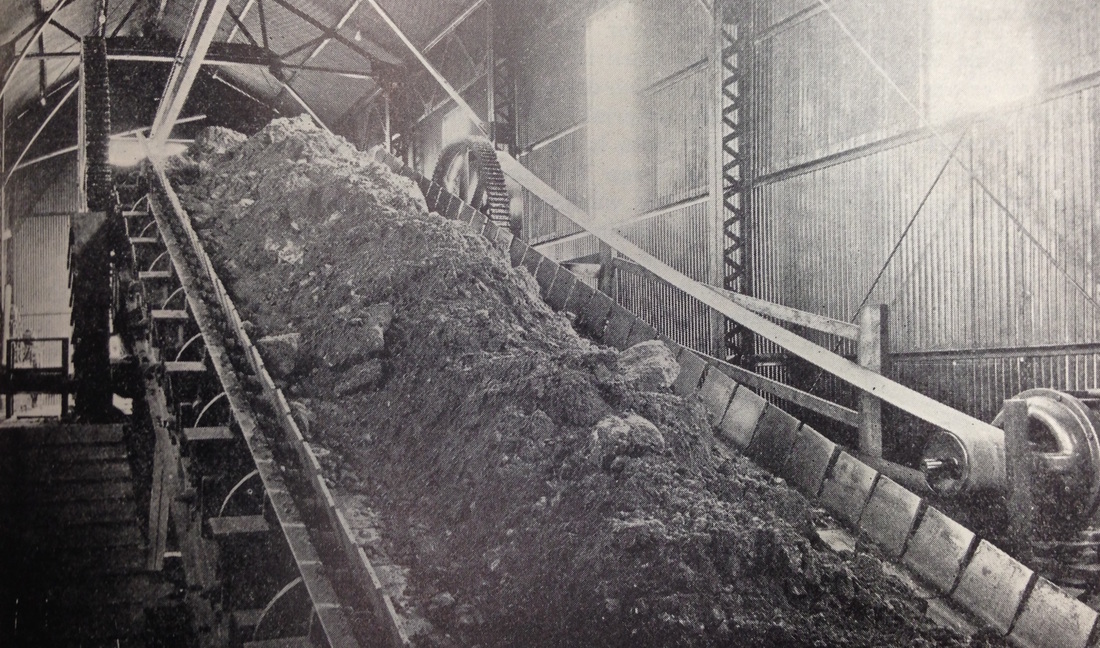

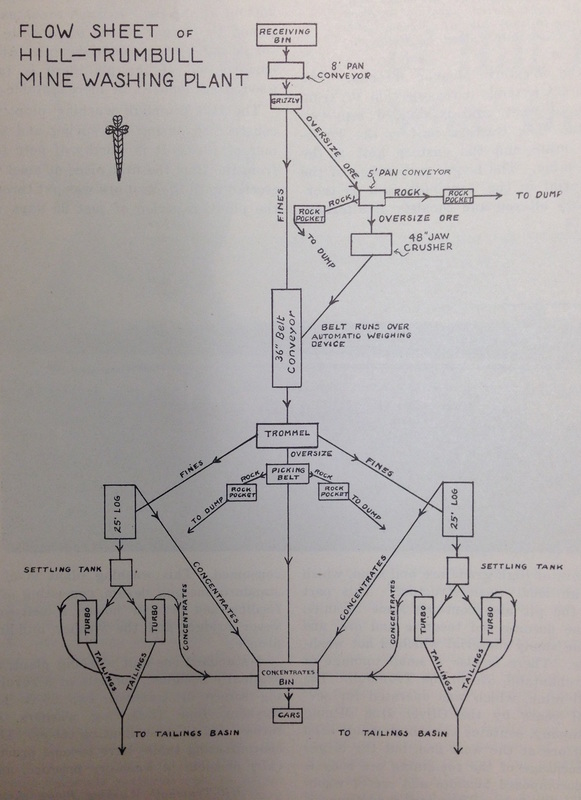

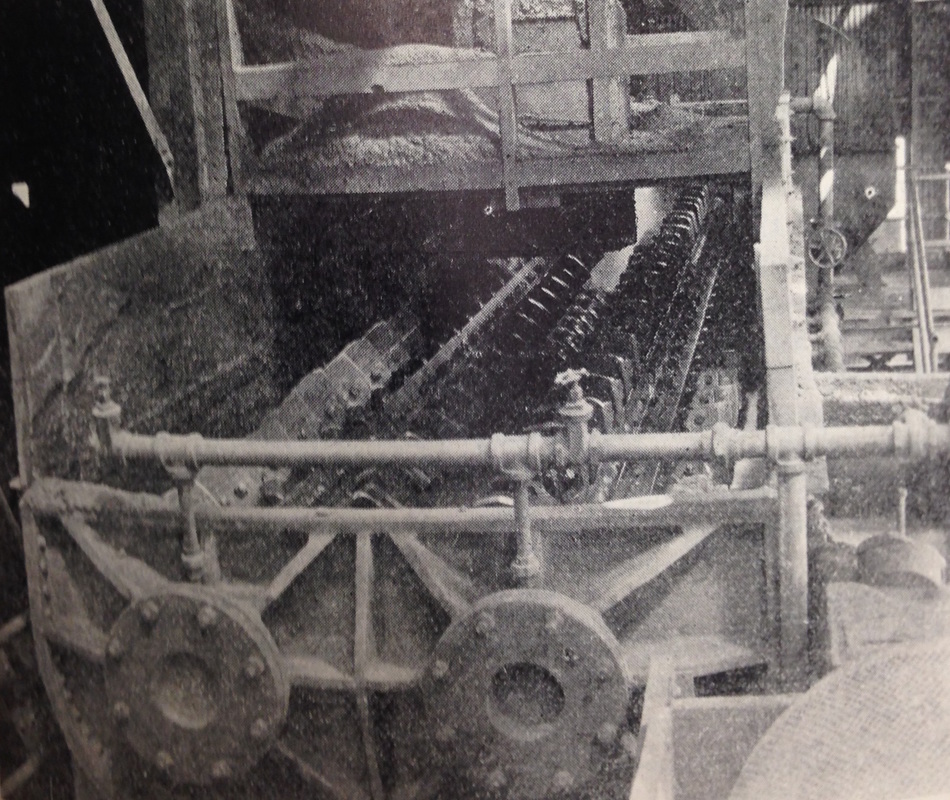

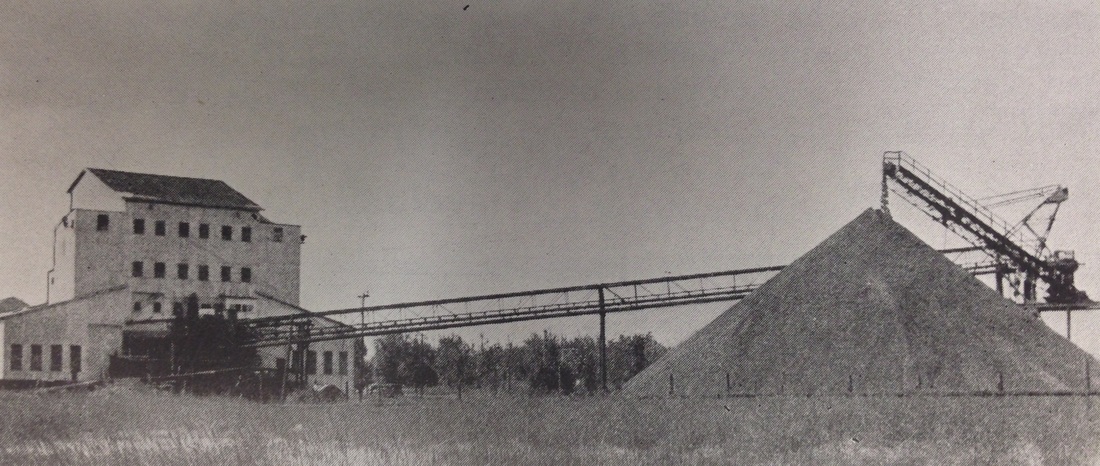

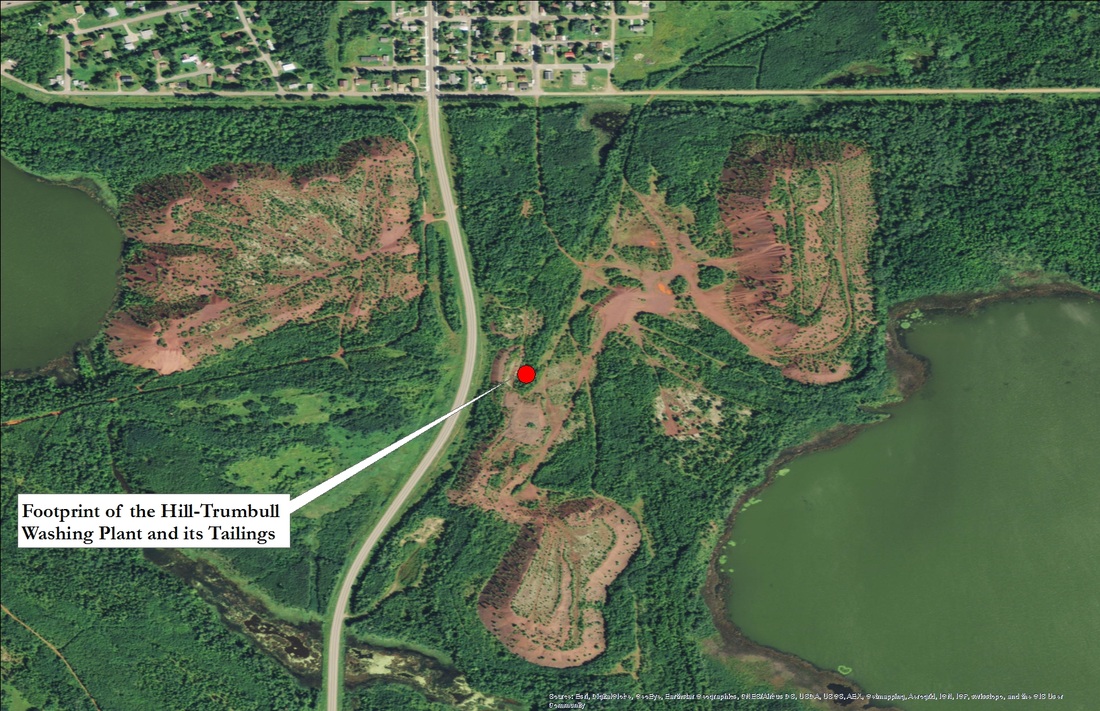

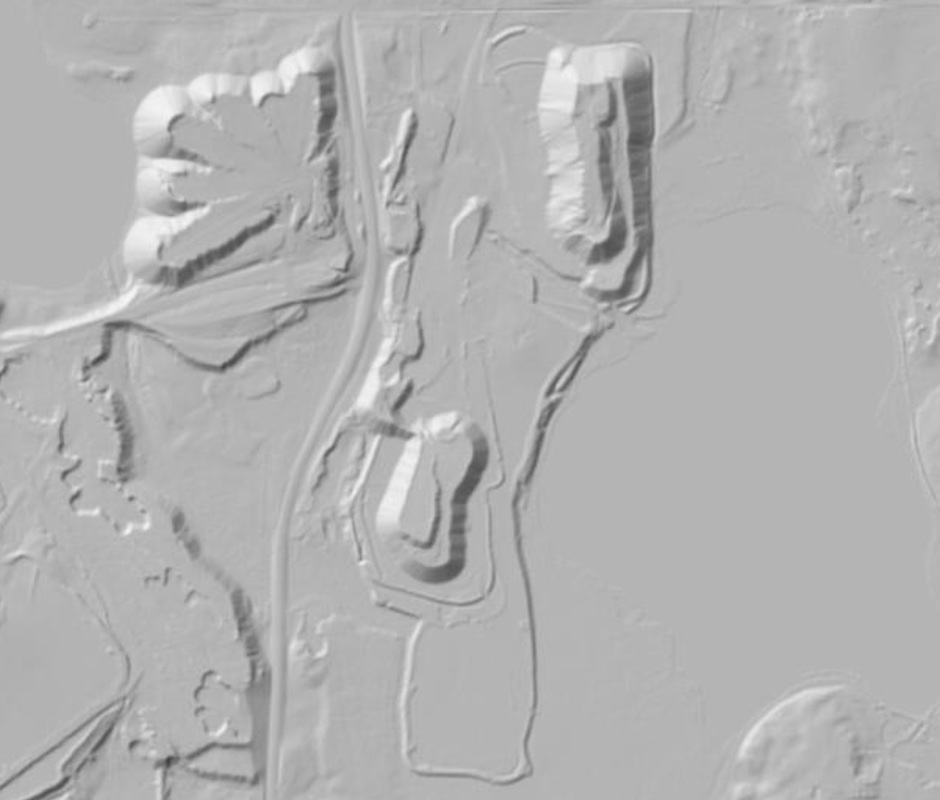

"The lake has a limited plant community due to poor water clarity and the shorelines have been disturbed by past mining activity." -MN DNR Upper Panasa Lake is small, murky, and unspectacular. Viewed from above, Upper Panasa Lake stands out from the dozen or so other lakes that surround Calumet, MN not because of its size or shape, but due to its pale green color - reminiscent more so of pea soup than as the aquatic home for bullhead, northern pike, and pan fish. Although its appearance may be drab, Upper Panasa's industrial past is quite vibrant, and it begins in part with the Hill-Trumbull washing plant and the 24-billion gallons of water it sucked from Upper Panasa Lake over half a century to process silica-laden low grade iron ore. Located just south of Calumet, MN and within the western Mesabi Range, Upper Panasa Lake was bordered historically by two low-grade iron ore washing plants, the Hill-Trumbull plant on its northwest bank, and the Hill-Annex plant on its eastern (-the latter of which stands as the sole washing plant within the Mesabi Range that has been recognized as a heritage site-). Unlike some of the custom mills this blog has examined in the past, the ore that was treated at the Hill-Trumbull washing plant came solely from the Hill-Trumbull mine, a long ore body that runs for nearly a mile. The Hill-Trumbull mine, which was first opened in 1909 by the Oliver Iron Mining Co., and the Mesaba Cliffs Iron Co, is actually two individual mines that were eventually consolidated, with the Trumbull mine lying within the western half of Section 17, and the Hill mine within the eastern half. The Hill mine's likely namesake was the noted "Empire Builder" of the Mesabi, the prominent railroad tycoon and land baron, James J. Hill. As the open pit mining operations at both of these mines expanded along the ore body their excavations eventually met, crating a vast cavity, seen in the aerial image above as the long lake just north of Calumet. For nearly the first decade of its operation the Hill-Trumbull mine employed selective mining - extracting only the pockets of high-grade direct shipping ore, found primarily at the Hill mine, while avoiding the vast tracts of silicious ore that made up the majority of Section 17. But, in 1919 the Mesaba Cliffs Iron Co. (the mine owner, nee Cleveland Cliffs) purchased a tract of land south of the mine and began drawing plans for the construction of a standard washing plant, tailored specifically for the siliceous ores of the Hill-Trumbull mine. Constructed in 1920, the Hill-Trumbull Washing plant joined the Hill-Annex washing plant as the two primary ore processing plants in the Calumet region. The location of the plants near Upper Panasa Lake was not happenstance, as we've seen with all ore processing plants, an abundant supply of water was as nearly as important to a mining company as was a profitable ore body - and Upper Panasa Lake just happened to fit that bill. Water for the Hill-Trumbull washing plant was pumped from Upper Panasa, by means of a pumping plant (situated on the southeast side of the levee line portrayed on the topographic map above). The pumping plant consisted of two pumps, a primary and an auxiliary, and delivered roughly 2,000 gallons per minute to the washing plant by means of a "20-in. spiral-riveted pipe line." H.C. Bolthouse, "Beneficiation of Hill-Trumbull Mine Ores", in The Mining Congress Journal, Oct. 1929, pp. 756). "It is worthy of note that, from the time the first piece of steel was erected until the first ore was put through the plant, a period of just 90 days was consumed." H.C. Bolthouse, "Beneficiation of Hill-Trumbull Mine Ores", in The Mining Congress Journal, Oct. 1929, pp. 753). The Hill-Trumbull plant was a standard one-unit plant, meaning that is consisted of specific technological components, including a primary crushing house, an ore conveyor, and, within the washing building itself, a trommel, log washers, and concentrating tables. The ore that arrived at the Hill-Trumbull washing plant came via train, and the plant was originally designed to handle "80 cars per shift ", a number that would grow along with the plant as it was retrofitted with improved technologies over the next forty years. (EMJ, Vol. 110, No. 10, 4 Sept. 1920, pp. 498) Within standard washing plants, water was introduced at almost every stage in the classifying and concentrating process. Briefly, the process at the Hill-Trumbull washing plant was as follows (though a more thorough description of individual technologies is provided in the write-up on the Coons-Pacific Iron Ore Concentrator): -After the ore was delivered to the plant, it was first classified and sized at the crushing plant, which consisted of the ore being dumped onto a grizzly, with the oversized material sent to a jaw crusher to further reduce the size of these larger chunks of ore, while the fine material fell through the slats of the grizzly onto a conveyor belt. Once the oversized ore was reduced to a size copacetic for treatment, a conveyor sent the ore up an elevated and covered conveyor to the washing plant. -At the washing plant, the ore was fed into a revolving trommel, where jets of water were introduced to the machine in order to help break up and remove any loose sand and debris from the ore as it was passed against the trommel's internal screen. -Next, the material from the trommel (both the classified ore and the water), along with additional fresh water are processed within a log washer, which, in the case of the Hill-Trumbull, were 25-foot long machines set at a declined tilt, that contained paddle-lined shafts rotating at a moderate speed of 15 rpm. The log washers were arranged at a tilt so that the lighter fine material and tailings would travel downward and flush out of the washer's bottom opening, while the heavier and coarse material would be forced upwards thanks to rotation of the paddles. -The coarse material would be discharged through the elevated end and sent to concentrate bins. The overflow and the material that was flushed out of the washer's bottom were next introduced into a series of turbos, a device similar to the log washers, except the shaft rotated at a slower speed, aimed at processing much more delicate material. The fines from the turbos laundered into the nearby tailings basin. H.C. Bolthouse, "Beneficiation of Hill-Trumbull Mine Ores", in The Mining Congress Journal, Oct. 1929, pp. 755-756). The amount of water needed to wash the silica-laden ores in the Mesabi Range varied by ore body and by technology, but on average 900 gallons of water were required to process one ton of washable ore. In the case of the Hill-Trumbull, which shipped a total of 27,128,463 tons of ore during its operation, this equates to nearly 24.5 billion gallons of water, a hefty sum considering the meager size of Panasa. Why the Hill-Trumbull and other washing plants in the region decided to construct tailings basins rather than simply dump their waste in nearby waterbodies or swampland is unknown (although I do hope to discover this during my research). It is possible that legislation was already in place that forbid the direct dumping of mine waste into water bodies. It is also possible that Cleveland Cliffs planned on reclaiming some value from these tailings at a later date through an improved technology. Nevertheless, the roughly 3,500-ft x 1,000-ft. basin was constructed around 1920 on a "tract of low swamp land...lying between the washing plant on the west end and Little Penacie Lake on the east side. This area is not a naturally inclosed basin, therefore it has been necessary to cast a dike along the north, east, south and part of the west sides in order to prevent the tailings from flowing into the lake." (note the spelling of Panasa Lake here as well as Panaca on the topographic map above). H.C. Bolthouse, "Beneficiation of Hill-Trumbull Mine Ores", in The Mining Congress Journal, Oct. 1929, pp. 756). In the Mesabi Range, tailings basins contained both mineral waste, such as silica, as well as large amounts of wash water that was used during the beneficiation process. Mixed together, these ingredients create a brown stew with a constitution similar to the stuff found at the bottom of a pot of cowboy coffee - silty and murky, but still liquid. Since the tailings produced in the washing plants of the Mesabi had a liquid consistency, the tailings basins constructed to contain them needed strong walls - and if the mining company was attempting to maximize the internal volume of the basin, a dewatering system would allow more room for the solids by removing the abundance of liquid. At the Hill-Trumbull tailings basin, Cleveland Cliffs installed such a dewatering system. The Hill-Trumbull system used adjustable overflow pipes to remove the water that sat atop the settled tailings. These pipes could be raised or lowered depending on the state of the tailings, with a calm basin allowing for the pipes to depress further into the basin, while a turbid basin would suggest that the pipes should be raised until the tailings settled. The water removed from the tailings basin was simply pumped directly back to Upper Panasa Lake, as no filtration or treatment was deemed necessary. Although erecting the Hill-Trumbull washing plant was completed in a matter of mere months, the construction and maintenance of its tailings basin and dike required ongoing construction and maintenance in order for it to effectively contain the continual flow of tailings that emanated from its launders. The walls of the tailings basin at the Hill-Trumbull were constructed from the tailings themselves - which over the course of its lifetime amounted to over 40-million tons. Cleveland Cliffs employed a gasoline powered dragline excavator to dig up the tailings at the bottom of the basin and then continually restacking them as it built up and fortified the basin's walls. H.C. Bolthouse, "Beneficiation of Hill-Trumbull Mine Ores", in The Mining Congress Journal, Oct. 1929, pp. 756). During the midst of the Great Depression, the Hill-Trumbull mine, like many other mines, was left idle. There is little published accounts of the washing plant from 1929 until after WW2, and these accounts tend to be overly technical in nature, providing technical descriptions of new machines installed at the plant and the results of their operation. In 1948, Cleveland Cliffs added a spiral concentration section to the Hill-Trumbull plant in hopes that it would help capture some of the fines lost in the washing process. The spiral section at the Hill-Trumbull was massive, and consisted of 84 spiral units which were able to treat roughly 120 tons of siliceous ore per hour. Whitman E. Brown, "Humphreys Spiral Concentration on Mesabi Range Ores", in AIME Mining Transactions, June 1949, Vol. 184, pp. 187. "The prodigious amount of research devoted to the recovery of values in the fine ore reflects the dire need of the iron industry to squeeze the last possible unit of iron from the mined ore and to develop suitable equipment and processes to satisfactorily concentrate the leaner horizons as they are encountered in the process of mining." Whitman E. Brown, 1947 Two years later, the Hill-Trumbull plant expanded again, with Cleveland Cliffs installing a Hardinge Heavy Media Separator to the HMS section (this section was installed sometime between 1929-1949). "Cleveland Cliffs Iron Company Uses Separator on Trumbull Ore", Mining World, August 1950, pp. 37. A final addition was made in 1953, with Cleveland Cliffs erecting a cyclone plant, a relatively novel technology within the Mesabi at that time. By 1955 the Hill-Trumbull washing plant was treating 85 long tons of ore per hour, a significant decrease from the 1948 operation. R.A. Derby, "Cyclone Plant Improvements Up Recovery of Mesabi Iron Ore", in Mining World, March 1955. "At mid-1971, this property was closed because of the exhaustion of the economically mineable ore reserve. Presently, the heavy-media and washing plant, as well as other surface facilities are being dismantled by Mesaba Service & Supply Co." Skillings' Mining Review, Vol. 61, No. 23, 3 June 1972, pp. 17 By 1973, the majority of the Hill-Trumbull washing plant and its ancillary structures were disassembled and scrapped, as Cleveland Cliffs sought to reclaim whatever value was left within the obsolete steel structure of the plant, crushing house, and conveyor. The historical record never mentions the construction of a secondary tailings pile located to the west of the washing plant, but aerial imagery and LIDAR data tell a different story.

A strength of industrial archaeology is that it treats industrial landscapes as artifacts - that is these landscapes coupled with the historical record can help unravel new narratives about our past that we might not have uncovered otherwise. And unlike historical records, landscapes don't lie. Although it was constructed out of organic material, the tailings basin of the Hill-Trumbull washing plant is the last physical vestige of this ghost plant and it's half-century of operation. While Cleveland Cliffs boasted about the speed in which it erected the Hill-Trumbull washing plant, the modernizing of the plant with cyclones and spiral units, and the savvy nature of their metallurgists willing to tackle the ongoing challenge of beneficiation, it remains somewhat ironic that these piles of siliceous waste serve as the Hill-Trumbull's legacy. At certain scales, Upper Panasa Lake looks more like the creation of an unorthodox alfalfa farmer than a natural waterbody. This is because Upper Panasa Lake is categorized as eutrophic - meaning that it contains an abundance of nutrients, such as nitrates and phosphates - ingredients commonly found in fertilizers employed to accelerate the growth of plants. When these nutrients are introduced into lakes at an industrial scale, the response is similar to a farmer's field that has been treated with fertilizer. Plant matter begins to flourish, and competition for sun light soon favors those species that tend to grow and expand the fastest. In the case of Upper Panasa Lake, that species is algae. The rapid growth of algae in lakes, called blooms, creates a wealth of ecological problems, as the shortlived plants not only feast on the nitrates and phosphates, but as they die and decay they also consume vast amounts of oxygen, which slowly suffocates other aquatic life. The eutrophic state of Upper Panasa Lake is owed primarily to the sewage treatment plant that serves as one of its inlets, but I'd be willing to gamble that the industrial legacy of the Hill-Trumbull ghost plant, its tailings basins, and water plant continue to silently add to its distress.

1 Comment

Richard J Thouin

10/10/2021 14:05:25

I was a mining laborer, during the Summer of 1972 , recently home for the summer.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorJohn Baeten holds a PhD in Industrial Heritage and Archaeology from Michigan Technological University. His research aims to contextualize the environmental legacies of industrialization as meaningful cultural heritage. Archives

May 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed