|

Artifact (n): a characteristic product of human activity "What is the coolest artifact you have ever found?" Countless archaeologists have been asked this question, and when directed at me it has always posed a challenge. Was it a green obsidian spear point found in Northern California? A stamp mill battery in Alaska? A chert awl in Arizona?

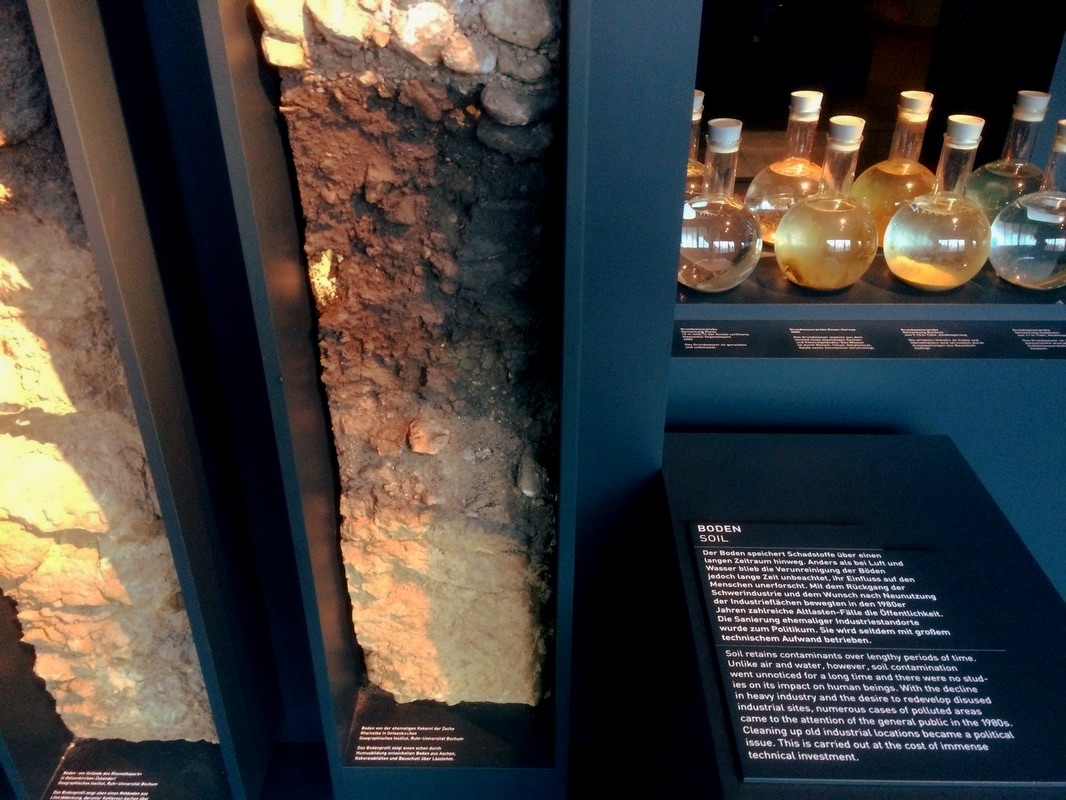

While I never have a quick answer to this question, what I do notice is that whatever my answer, the artifact is always something tangible, always something obviously human, and always rooted in technological materialism. I've been taught that an artifact is something mobile and something that was produced to serve some sort of purpose. Yet that is the orthodoxy of archaeology and heritage. What happens when we begin to challenge this convention? I was recently fortunate enough to visit some tremendous industrial heritage sites in Germany, the Landschaftspark in Duisburg, and Zeche Zollverein in Essen. At both of these sites it is easy to become overwhelmed by their sheer grandeur, one centered around an enormous blast furnace works, the other centered around a towering coal mine shaft house. While I thoroughly enjoy these megaliths of industrial prosperity, what resonated with me most was a collection of artifacts housed in the Zeche Zollverein museum exhibit - appropriately called, "Environmental Destruction and Protection".

1 Comment

|

AuthorJohn Baeten is a Postdoctoral Fellow in Spatial Analysis of Environmental Change in the Department of Geography at Indiana University. He holds a PhD in Industrial Heritage and Archaeology from Michigan Technological University. His research aims to connect historical process to current environmental challenges, and to contextualize the environmental legacies of industrialization as meaningful cultural heritage. Archives

September 2018

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed