|

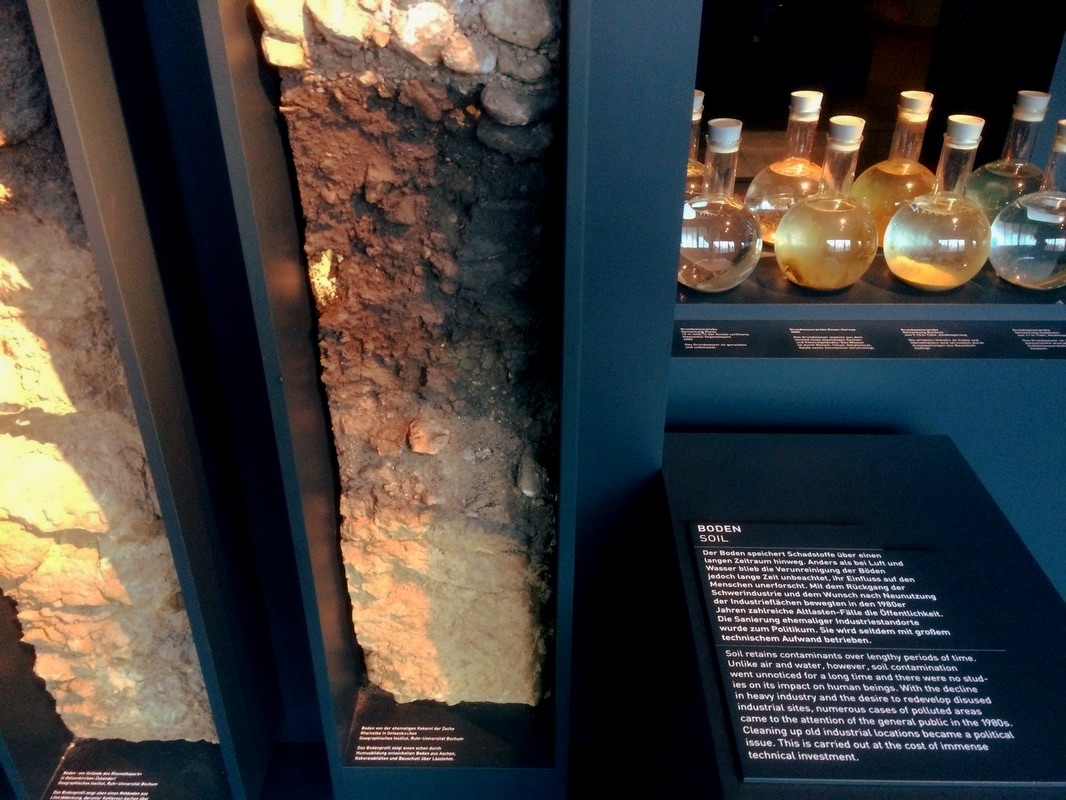

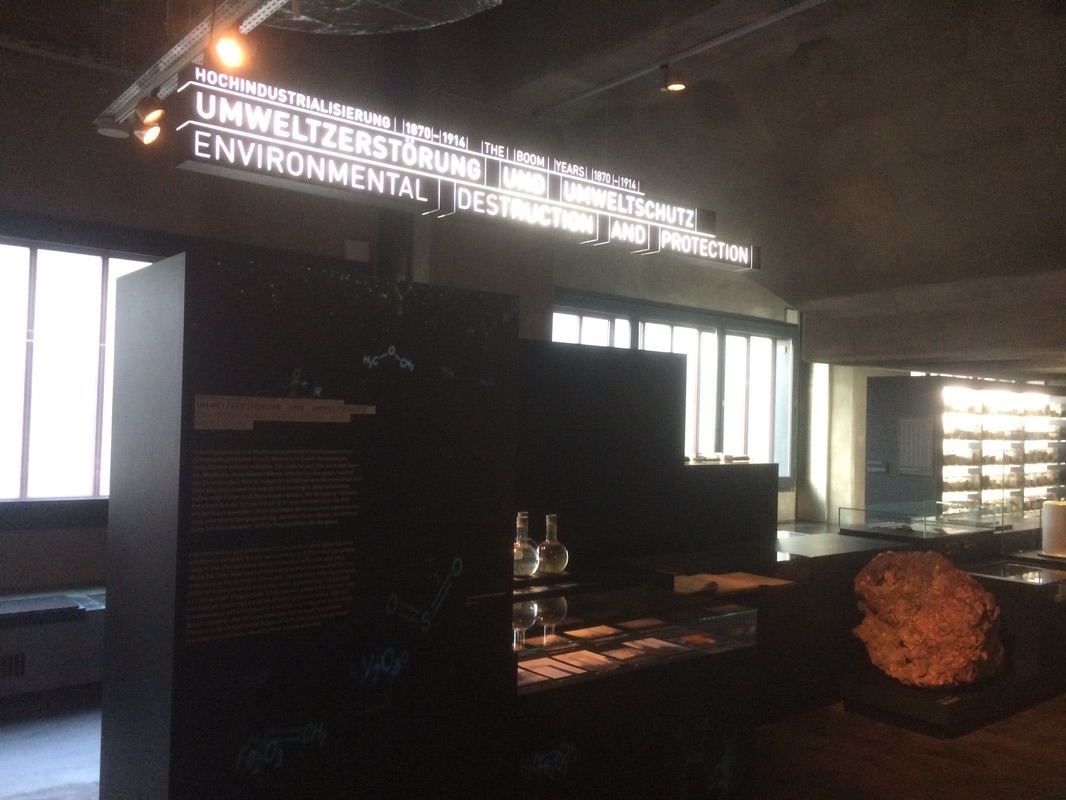

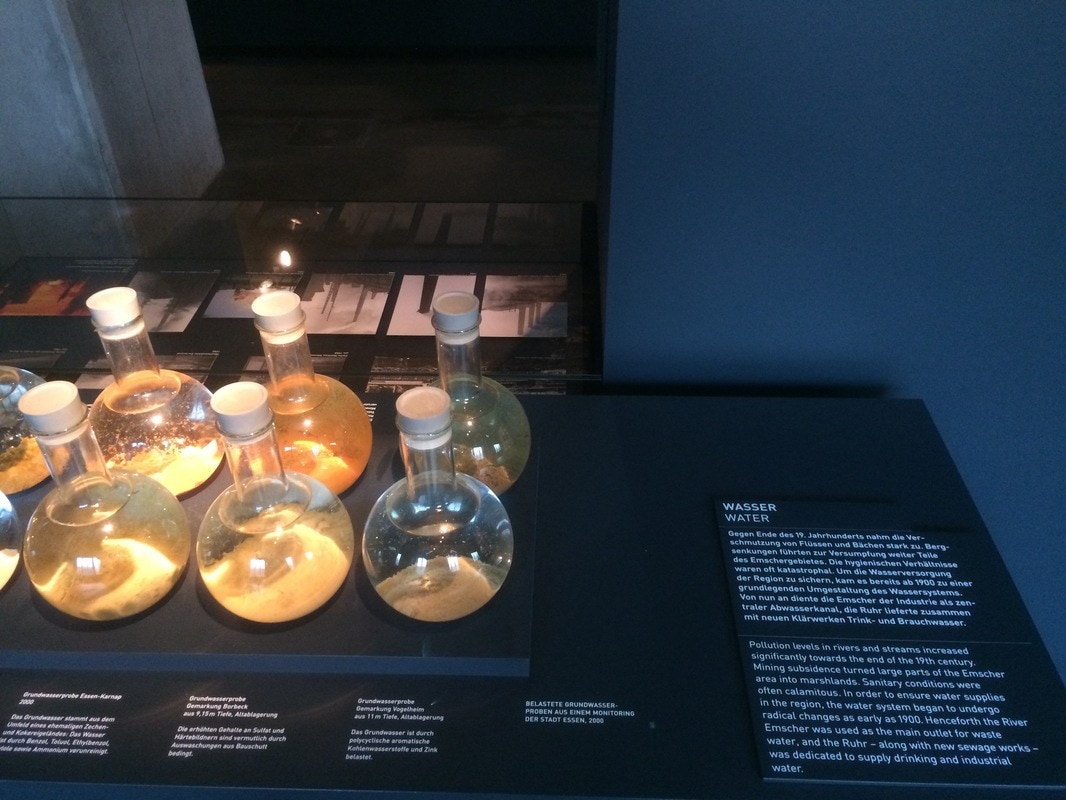

Artifact (n): a characteristic product of human activity "What is the coolest artifact you have ever found?" Countless archaeologists have been asked this question, and when directed at me it has always posed a challenge. Was it a green obsidian spear point found in Northern California? A stamp mill battery in Alaska? A chert awl in Arizona? While I never have a quick answer to this question, what I do notice is that whatever my answer, the artifact is always something tangible, always something obviously human, and always rooted in technological materialism. I've been taught that an artifact is something mobile and something that was produced to serve some sort of purpose. Yet that is the orthodoxy of archaeology and heritage. What happens when we begin to challenge this convention? I was recently fortunate enough to visit some tremendous industrial heritage sites in Germany, the Landschaftspark in Duisburg, and Zeche Zollverein in Essen. At both of these sites it is easy to become overwhelmed by their sheer grandeur, one centered around an enormous blast furnace works, the other centered around a towering coal mine shaft house. While I thoroughly enjoy these megaliths of industrial prosperity, what resonated with me most was a collection of artifacts housed in the Zeche Zollverein museum exhibit - appropriately called, "Environmental Destruction and Protection". Tucked away in a corner of the museum's 3rd level, the "Environmental Destruction and Protection" display contains jars and soil core samples filled with soils contaminated by industrial processes, and florence flasks containing polluted waters. I've long believed that mine waste constituted an artifact (although these are often called archaeological features - a semantic road we will not venture down in this blog post ), but I never really toyed with the idea of expanding the artifact categorization to include those less obvious products of human activity, things like contaminated soil and toxic water. But why not? Contaminated soils and polluted waters are products of industrial capitalism - some of the human made residuals left over from industrialization - comparable to a waste rock pile at a mine or a flake scatter at an indigenous camp. These are all the leftovers from a concerted effort by humans to create. So I ask: Can contamination or pollution = artifact(s)? and What new understandings of contamination could arise from archaeological interpretation? The National Archives has produced an artifact analysis worksheet, which serves as a useful guide for interpreting an artifact that you might find in the field or be tasked with analyzing in a lab. The questions on the worksheet follow the journalistic standard of knowing, asking: Who, What, Where, When, Why, and How the artifact in question came to be. But, more importantly the worksheet asks: "WHAT DOES THE ARTIFACT TELL US?" Explaining why an artifact matters to the public is the key task for an archaeologist. About a decade ago, I remember coming across a massive can scatter in the Lake Tahoe region. I measured these cans, took photographs, and compared them to a handy artifact guide to determine their age. What I learned was that this pile of rusty metal was dumped there in the 1940s. Some folks had set up a camp, possibly for logging or railroad maintenance, and this was what they left behind. The interpretive value of sites like these are low and tell us very little in the grand scheme of things: people consumed goods here, and these same people were careless with their trash. Moral of the story, Don't Litter. "Industrialization and growth soon threw up their dark sides. Harmful substances pervaded the air, water and soil." (Zeche Zollverein museum display) Industrial heritage, broadly, is the study of capitalism - looking specifically at the products that were produced (and left behind) from industrial scale processes.

However, the primary focus of industrial heritage has been centered on two elements: the study and preservation of large industrial buildings and machines, and the promotion of historic industrial sites for tourism purposes. Both of these endeavors tend to celebrate nostalgia, and unintentionally promote the capitalist epistemologies that produced these places and things. Neither approach acknowledges the sheer abundance of environmental destruction wrought by industry. In fact, it can be argued that the most ubiquitous and important product created from industrial capitalism is its environmental legacy. So why not embrace contamination and pollution as meaningful artifacts of industry's past? What other stories might these pollutants tell us when interpreted not just through chemical analysis, but studied through an archaeological or sociotechnical lens? To return to the National Archive's Question: "What does the artifact (contamination) tell us?" I believe artifacts like contaminated soils and polluted water hold a great deal of interpretive value - but more importantly I wonder what can archaeologists infer from these artifacts of industrial misuse, and how can this knowledge inform the public and policy makers who must interpret, manage, and live within these industrial landscapes? What do you think?

1 Comment

|

AuthorJohn Baeten is a Postdoctoral Fellow in Spatial Analysis of Environmental Change in the Department of Geography at Indiana University. He holds a PhD in Industrial Heritage and Archaeology from Michigan Technological University. His research aims to connect historical process to current environmental challenges, and to contextualize the environmental legacies of industrialization as meaningful cultural heritage. Archives

September 2018

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed