|

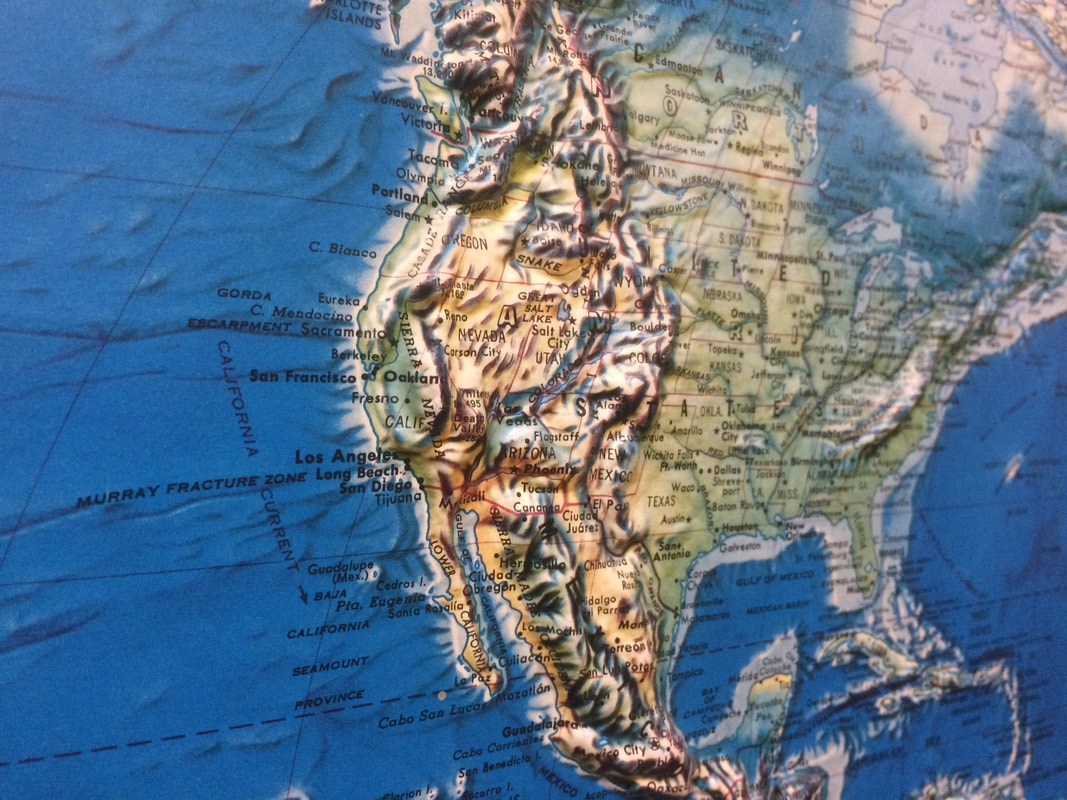

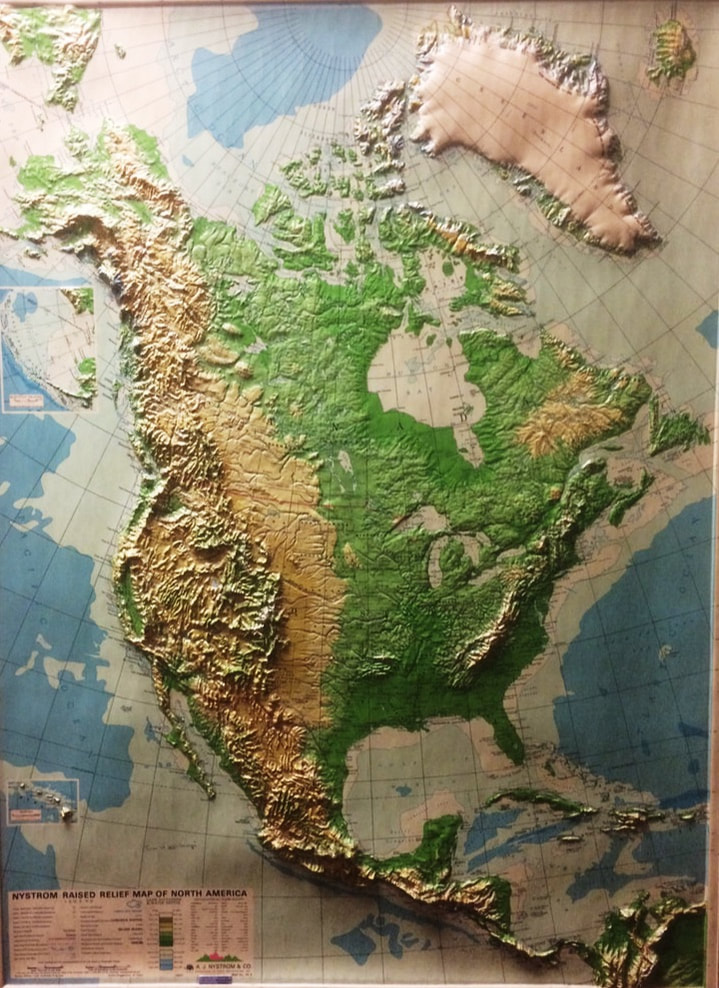

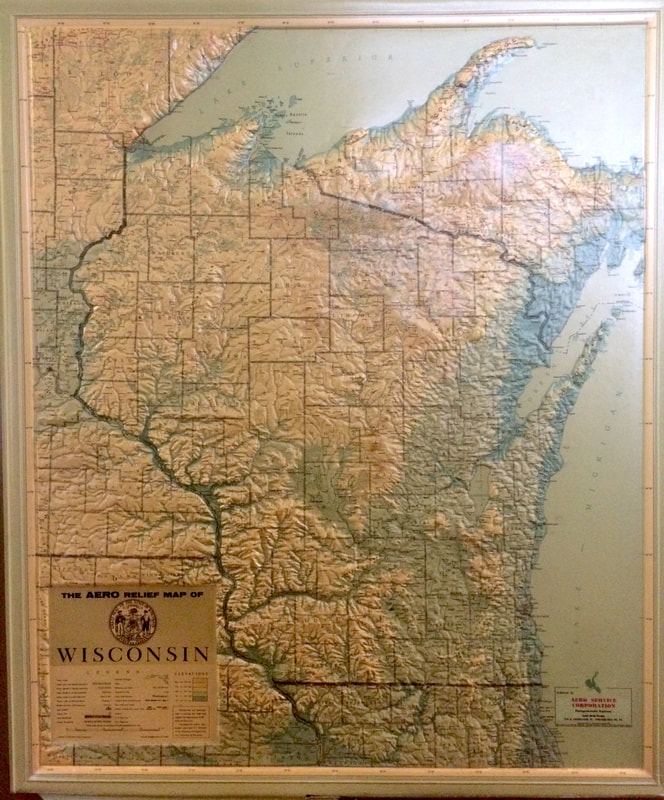

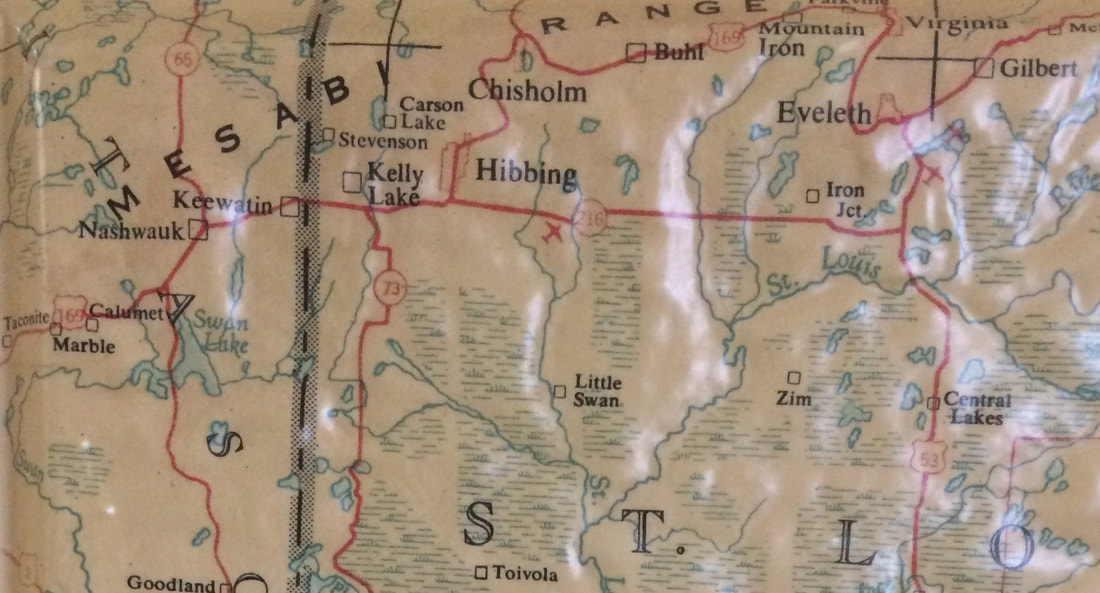

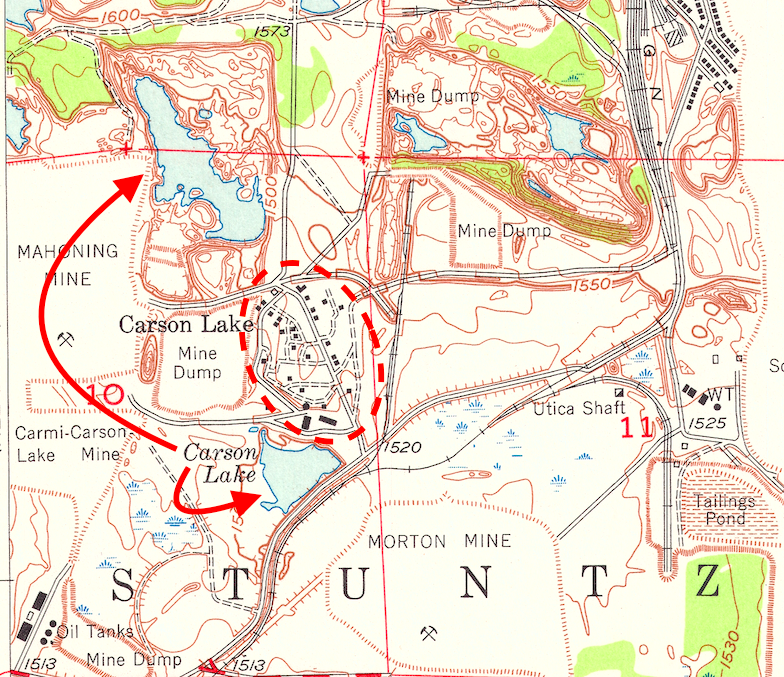

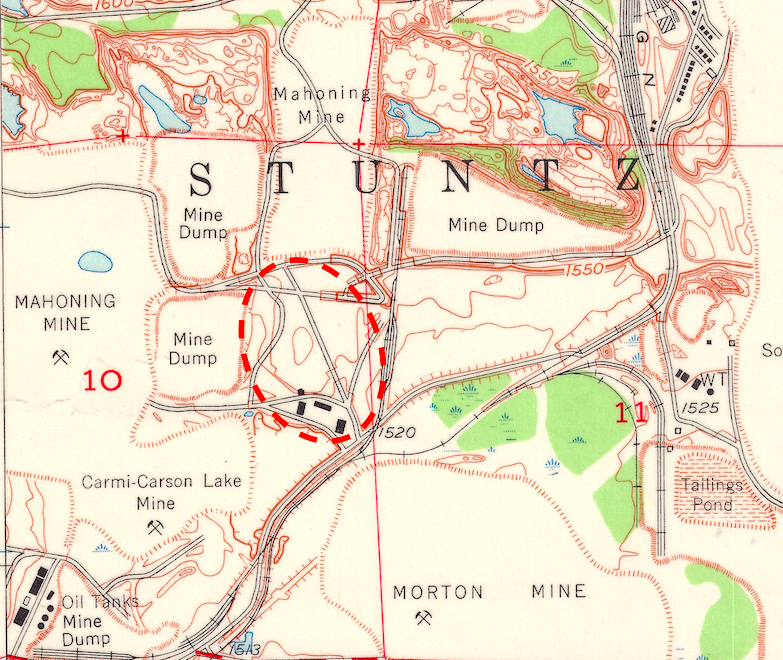

In 1955, Carson Lake did not exist Growing up in the flatlands of Northeast Wisconsin, I have long been fascinated with big topography and consistently drawn to maps - particularly those that use raised relief to depict elevation changes. Raised relief maps are models of reality that present landscape formations in 3-Dimensions - allowing the user to both see and feel the plains, valleys, and mountain ranges of the world. As a child, I remember being intrigued by the vast raised ridges that ran across the Americas - one flowing from Alaska to New Mexico, and another running through Ecuador, Peru and Chile - places in which I would later work, travel, and live. These raised relief maps brought the dramatic geologic formations that occupy much of the western extent of the Americas to the classrooms of the topographically challenged Midwest. In my current office building at Michigan Technological University, a number of raised relief maps are conveniently hung in the hallway running next to the office microwave. I've found myself casually perusing these historical maps when waiting for my lunch to heat up. What I've seen during these lunch-time inquiries is that these physical artifacts, also contain geographic artifacts left over from past cartography - and I'd be willing to guess, that I might be one of the first archaeologists to identify an intriguing artifact while waiting for their soup to cook in a Haier microwave. But I digress. One of these maps is of Wisconsin, which includes the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, home to Michigan Tech, and the Arrowhead area of Northern Minnesota, home to the Mesabi Iron Range. Owing to Wisconsin's relative flatness, this 1955 map uses a raised relief at a 20X vertical exaggeration, which allows for points like Timms Hill (the State's highest "peak") to stand out a little more. Since my research has been focused on the Mesabi Range, my eyes have tended to focus on the landscape of Northern St. Louis County. A primary objective of archaeological inquiry is looking for artifacts or cultural features that might signify past human activity on the landscape. Maps, like landscapes, also contain artifacts,just not the physical tools that normally inspire archaeological investigation. In my work as an archaeologist and environmental historian, I've come across a lot of these cartographic artifacts when looking over maps - namely, phantom cabins, fire towers, roads, fences, water tanks, and towns - features that persist on maps decades after they were burned down, closed, or removed from the landscape. However, the cartographic artifacts that I've become accustomed to, are tied together by their cultural origin. And that is partially why the artifact I found on the 1955 Aero Service Corp. relief map of Wisconsin so intriguing - because it was not a ghost town, such as Elcor, MN - but instead, this artifact just happened to be a lake. In 1955, Carson Lake did not exist The Carson Lake shown on this 1955 map is an artifact - in fact it hadn't existed for more than three decades. Once the largest body of water located within a 5 mile radius of the Mesabi Range's largest community, Hibbing, Carson Lake had been effectively removed from the landscape over a two-year period from 1917-1919. During this time, the Oliver Iron Mining Company, who had located iron ore underneath the lake years earlier, secured permits from the State of Minnesota to mine underneath the lakebed. "Carson Lake property, near Hibbing, Minn., which was diamond drilled through the ice years ago, and later drained and then filled with overburden from the Kerr mine stripping operations, will now be developed and put on producing basis as soon as possible...Considerable trouble is anticipated due to unusual location of the ore body. "1 In my upcoming article in Change Over Time, "Contested Landscapes of Displacement: Oliver Iron and the Hibbing Mining District," I provide an overview of the promotion (featuring cross-section models displayed at the Minnesota State Fair), development, and ultimate failure of the Carson Lake mine - an industrial endeavor that operated for less than one year, but still managed to remove a lake from the landscape. The cartographers from the Aero Service Corp. who designed the map of Wisconsin in 1955 weren't alone in their depiction of this phantom waterbody. Examining the 1951 USGS topographic map shown above, Carson Lake, and its namesake community (outlined in red) also appear. This inclusion inspires some questions: Is it possible that water might have re-entered the former lakebed over the 30-year period since the Carson Lake mine was closed, and this is what was captured on these maps? Or could it be a mapping oversight, where the cartographers were possibly relying on an older map to re-draw the area? Six years later, the 1951 TOPO map was revised, and in this iteration, the Carson Lake waterbody and community were removed (as a side note- by this time the community had been displaced by the newly opened Carmi-Carson Lake open-pit mine). Cartographers revise maps in order to adjust for landscape changes, and to help capture the currentness of a specific space and place. When I started this post, I didn't foresee myself conducting a cursory examination of the process involved in topographic map revisions, but the historical processes used by the USGS is a truly interesting subject. According to this linked article by Larry Moore of the USGS, topographic maps underwent four main types of map revisions: minor, basic, complete and single edition. From what I see on the 1957 revision, this map likely underwent a basic revision - meaning that USGS cartographers addressed known errors within the 1951 map, and then used geospatial materials available to them in 1957, such as aerial imagery, to attempt to make the revised landscape as accurate as possible.2 Geographer Mark Monmonier has written extensively about the cultural decisions that go into maps - both in terms of the changing place names assigned to geographic features, as well as how these models of space and place reflect human agency, and can be used as tools to either promote or undermine certain landscapes. While I do not think that there was any nefarious motive behind the depiction of Carson Lake on these maps - it shows how these models of reality can perpetuate geographic distortions, as well as how little we might actually know about the landscapes in which we live or study. But what I find most intriguing about Carson Lake appearing on these maps decades after it was dewatered, mined, and eventually filled with mine waste - is thinking about how people in the past might have responded to seeing this feature on a map? What would have Mesabi Range residents, and particularly those living in Hibbing, thought if they had seen this phantom waterbody on the map? Might have it inspired a field trip to investigate this place, to see if by chance the lake had reappeared? Have you ever encountered a cartographic artifact, and if so, what was it?

3 Comments

5/1/2018 17:47:40

This really looks promising. I won't be surprised if all these adventures and discoveries while doing some research on this subject will end up in the movies. The guys behind will eventually become one of the most popular people in the world. The industry leaders will surely include this in all their expansion plans and business portfolio. I am very happy with what's happening with these people. They must have done something really remarkable in their past lives to enjoy this recent popularity.

Reply

JoAnne M. Haberkorn

5/12/2021 10:57:47

Happened to find your article while doing a little research on Carson Lake, MN. I was curious to see what I might find since my mother told me she was born there in 1923. She also said it no longer existed. Very interesting article. Thanks!

Reply

Bill Christofferson

7/31/2022 16:35:18

My mother, Elizabeth (Betsey) Shalloe, was born there in 1918. She had brothers Frank and Mackey. They lived with aunt and uncle Pat and Molly Kavanagh, who seemed to be the only Irish there.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorJohn Baeten is a Postdoctoral Fellow in Spatial Analysis of Environmental Change in the Department of Geography at Indiana University. He holds a PhD in Industrial Heritage and Archaeology from Michigan Technological University. His research aims to connect historical process to current environmental challenges, and to contextualize the environmental legacies of industrialization as meaningful cultural heritage. Archives

September 2018

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed