|

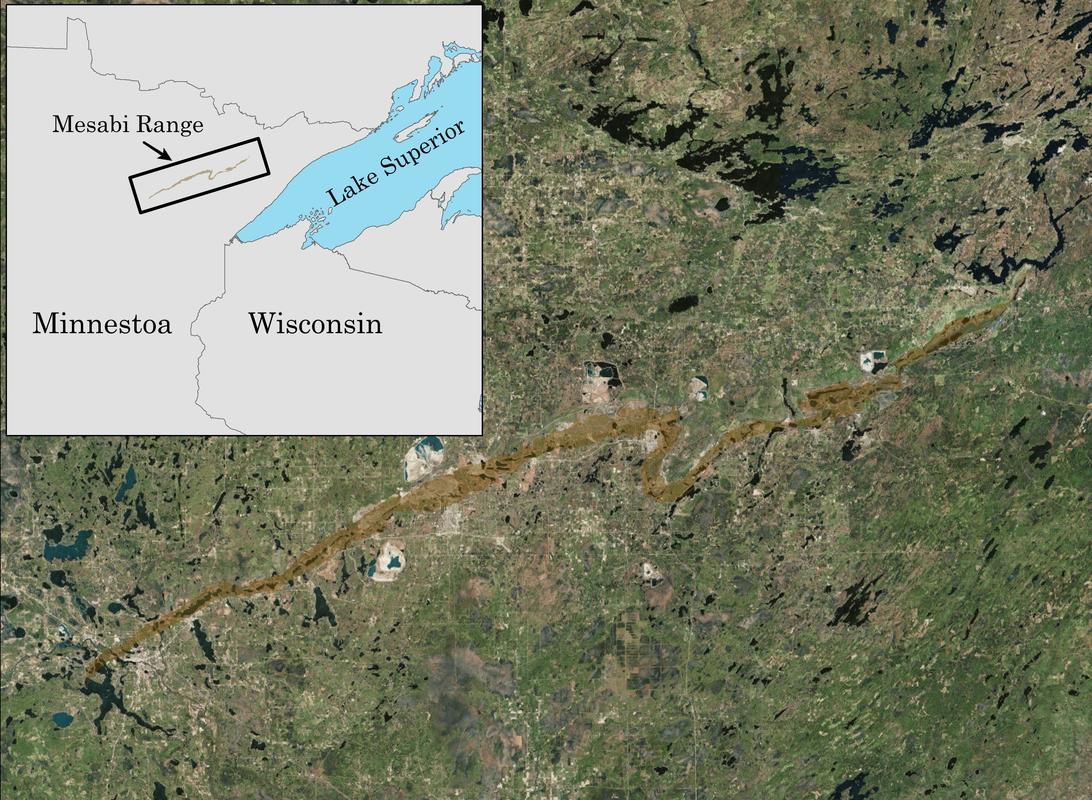

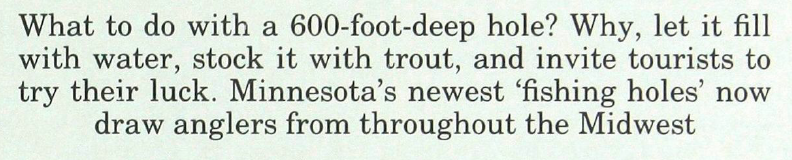

Post-mining landscapes often lie. What we see on the landscape today does not necessarily reflect the complex history in which that landscape was shaped. Instead, post-mining landscapes tell a story designed to convey a specific message to the public, often designed by either heritage organizations or reclamation agencies. In most post-mining landscapes, the story told by heritage organizations is often centered on either mining technology or architecture, seen in the focus on memorializing monuments representative of industrial capital. Consequently, the story that industrial heritage managers tell about post-mining landscapes often revolves around the interpretation of only a select few buildings and machines. However, these tangible manifestations make up only a small percentage of the post-mining landscape, while the overwhelming environmental impacts from mining are generally avoided. Likewise, reclamation agencies wish to convey a story that speaks of environmental cleanup, told through the recontouring and revegetating of waste piles, and the removal of derelict buildings. These reclamation efforts obscure many visible signs of mining, while presenting a landscape to the public that has been seemingly re-naturalized. Yet, reclamation often functions like a band-aid on a tumor, as immediate physical hazards are prioritized for remediation while the more widespread contamination is often left unaddressed. In Minnesota’s Mesabi Iron Range, the post-mining landscape tells a story of state-driven heritage strategies and reclamation efforts aimed at rebranding the range as a recreational rather than deindustrialized landscape. Located in Northern Minnesota, and extending for nearly 100-miles, the Mesabi Range was North America’s most productive iron range. From 1890 to today, more than 400 mines operated on the Mesabi Range removing over 3.8-billion tons of iron ore, the majority of which was extracted from highly efficient open-pit mining methods. Open-pit mining produces massive landscape transformations, evident in piles of mine waste along with deep surface chasms, impacts that persist long after a mine ceases production. During the late 1960s to 1970s, the Mesabi Range witnessed an increase in open-pit mine closure and abandonment, which accelerated the Range’s transformation from an active to a post-mining landscape, reflective of the economic, social, and environmental consequences of an industry based on a finite resource. Beginning in the 1970s, state land managers and local communities began to grapple with how to reckon the landscape transformations that accompanied mine land closure and abandonment. Realizing that the Mesabi Range was entering a post-mining epoch, state personnel began to develop strategies to reimagine and rebrand the Mesabi as something more than a post-mining landscape, by promoting the Mesabi Range as a recreational destination cushioned with a rich and ongoing mining history. This process included the reclamation of the post-mining landscape, consisting of the revegetation of mine waste piles, and the removal of derelict buildings. Steps were also taken to bolster the Range’s heritage tourism economy, through the installation of a rails-to-trails system, and the marketing of active mine-viewing areas to promote the ongoing efforts of the iron mining industry. In rebranding the Mesabi Range as a recreational landscape, the Minnesota DNR also made use of the abundance of new surface waters. As open-pit mines were closed and abandoned, the pumps used to dewater them were shut off, creating a veritable landscape of water. Today, there are 250 more lakes in the Mesabi Range than existed in 1890. Called pit-lakes, these waterbodies are the result of open-pit mining and abandonment, and represent a hydrological contrast from the dereliction that often defines a post-mining landscape. By the late 1970s, the Minnesota DNR began stocking these lakes with trout, hoping to lure Midwestern anglers to the region with this new renewable resource. Although this fish-stocking program has been met with much success, these pit-lakes are currently managed by the DNR as natural resources rather than historic mines, blurring their cultural significance. Yet, the stocking of trout into these abandoned mines has also functioned as an unintentional form of landscape conservation and an innovative approach to adaptive re-use. Today, visitors in the Mesabi Range can fish for trout in abandoned mines, as well as scuba dive in the former chasms of the Sparta and Gilbert mines, collectively known as Lake Ore-Be-Gone (a tongue-in-cheek reference to the Garrsion Keillor’s Lake Wobegon). At Lake Ore-Be-Gone, scuba divers can explore a number of out of place artifacts, including a helicopter, a bus, a pirate skeleton, and a WWII era military plane – adding a layer of confusion for future archaeologists. Check out this video for a great look at what people encounter in this historic mine. Negotiating post-mining landscapes, like the Mesabi Range, present challenges for communities, land managers, and heritage organizations. Although mining may have ceased, communities within these landscapes often persist, as do the environmental legacies of extraction. It is the responsibility of heritage managers to articulate to communities and to the broader public not just the features on the landscape that they have selectively memorialized, but also the abundance of environmental impacts that may have become obscured by either reclamation or heritage efforts. Doing so provides a more honest interpretation of the post-mining landscape and helps ensure that future generations won’t forget how these landscapes came to be, or what latent mysteries they might still contain. Further Reading:

Baeten, John, Nancy Langston, and Don Lafereniere, “A geospatial approach to uncovering the hidden waste footprint of Lake Superior’s Mesabi Iron Range,” The Extractive Industries and Society, Vol. 3, No. 4 (Nov. 2016) 1031-1045. Baeten, John, “Contested Landscapes of Displacement: Oliver Iron and the Hibbing Mining District,” forthcoming in Change Over Time: An International Journal of Conservation and the Built Environment (Fall, 2017). Goin, Peter, and Elizabeth Raymond, Changing Mines in America (Santa Fe: The Center for American Places, 2003). Langston, Nancy, Sustaining Lake Superior: An Extraordinary Lake in a Changing World (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017). Manuel, Jeff, Taconite Dreams: The Struggle to Sustain Mining on Minnesota’s Iron Range, 1915-2000 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015). Svatos, Ray, “Fishing Minnesota’s Abandoned Iron Pits,” Minnesota Conservation Volunteer, Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (July-August, 1986) 14-18.

1 Comment

|

AuthorJohn Baeten is a Postdoctoral Fellow in Spatial Analysis of Environmental Change in the Department of Geography at Indiana University. He holds a PhD in Industrial Heritage and Archaeology from Michigan Technological University. His research aims to connect historical process to current environmental challenges, and to contextualize the environmental legacies of industrialization as meaningful cultural heritage. Archives

September 2018

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed