|

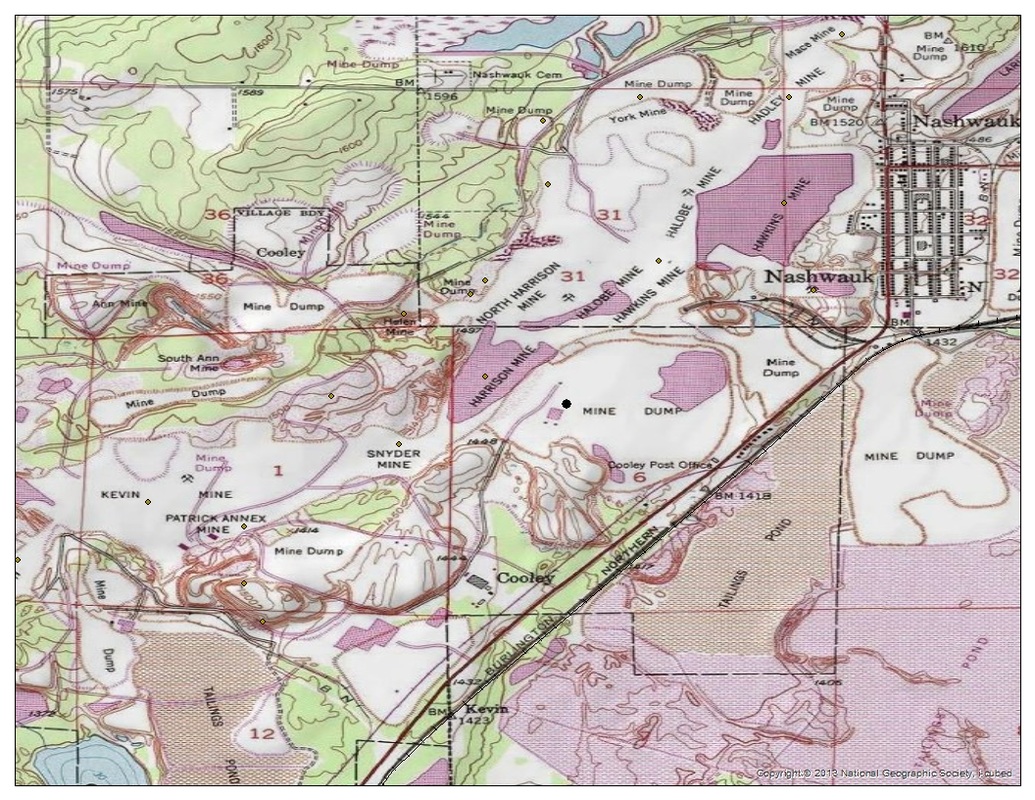

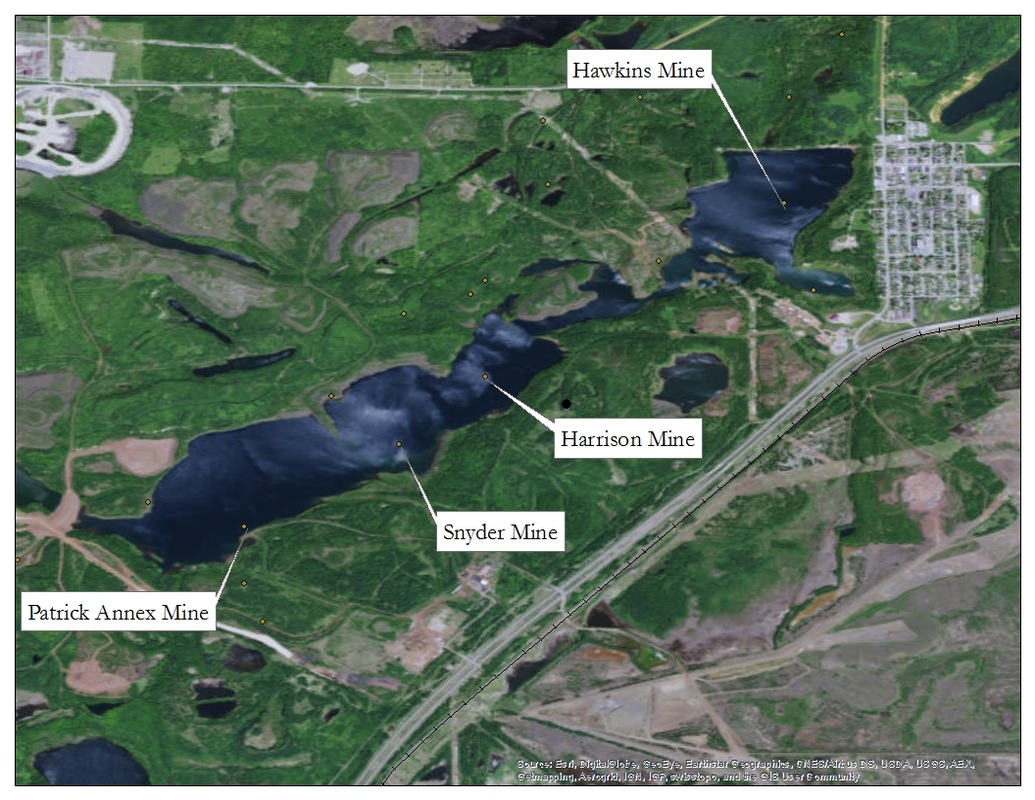

I'm in the process of testing a hypothesis on the heritage process, visibility, and remembering in the Mesabi Range. I believe that there is a much higher percentage of historic mines that are still visible on the landscape compared to the ghost plants, and this is one of the reasons why the mining pits have tended to dominate the contemporary heritage discourse of the Lake Superior Iron District, even though their environmental footprint may have been less impactful than the invisible ghost plants. To test this assumption, I've been surveying aerial imagery of the Mesabi Range to see how many former mines and their waste piles are visible on the landscape, as well as their associated ghost plants. In doing so, I've become amazed by how many water bodies are dotted across the post-industrial landscape - granted this is the land of 10,000 lakes - and thought this would be a good time to post a rhetorical question that I continue to dwell on - How do you interpret a mine that has become a lake? Mining landscapes are seldom static - instead they exist in a state of constant transition. In my thesis work I explored historic placer mining landscapes in Fairbanks, AK, and sought to categorize and date mining landscapes based on the technological systems that created them. In Fairbanks the earliest placer mining methods were carried out utilizing a drifting system, where miners would sink shafts (through frozen gravels) to bedrock and then run horizontal drifts off the bedrock floors. Since gold is heavier than gravel, the bedrock is where the gold nuggets ended up. As new technologies entered the subarctic, the drifting method was replaced (a bit of an over generalization here) by open-cut mining, which used water, bulldozers and drag lines to remove large swathes of overburden and exploit the bedrock in a much more efficient, albeit, invasive manner. Soon dredges made there way North and these too found a home in the transitioning mining landscape of Fairbanks - sometimes reworking the open-cut landscape that re-worked the drift mining landscape. Dating these landscapes was more difficult than I first thought, but it was a fun exercise nonetheless. In the Mesabi we see underground mines that, as technologies advanced, were converted into open pits, and then individual open-pit mines that were eventually consumed by a giant pit - the product of what Tim LeCain calls "Mass Destruction". As the ore deposits at these mines became exhausted the mining efforts waned and the dewatering pumps were shut off allowing ground water to seep up and fill the pit that once (and often still does) housed backhoes, tramways, and other mining infrastructure. Natural processes created a lake where a mine used to be. But the mine isn't gone, it lingers like a dormant Jason Voorhees waiting for camp counselors to arrive at Crystal Lake, or as what Arn Keeling and John Sandlos call "Zombie Mines". Articulating to the public and to policy makers the importance of what happened at these sites in the past, how these mines and plants continue to shape the cultural and natural landscape today, and how we might be able to do better in the future is the challenge at hand.

1 Comment

4/29/2021 11:25:15

It's interesting to learn more about mining. This is probably why my husband said he needs submersible pumps. He needs them to be reliable.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorJohn Baeten is a Postdoctoral Fellow in Spatial Analysis of Environmental Change in the Department of Geography at Indiana University. He holds a PhD in Industrial Heritage and Archaeology from Michigan Technological University. His research aims to connect historical process to current environmental challenges, and to contextualize the environmental legacies of industrialization as meaningful cultural heritage. Archives

September 2018

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed