|

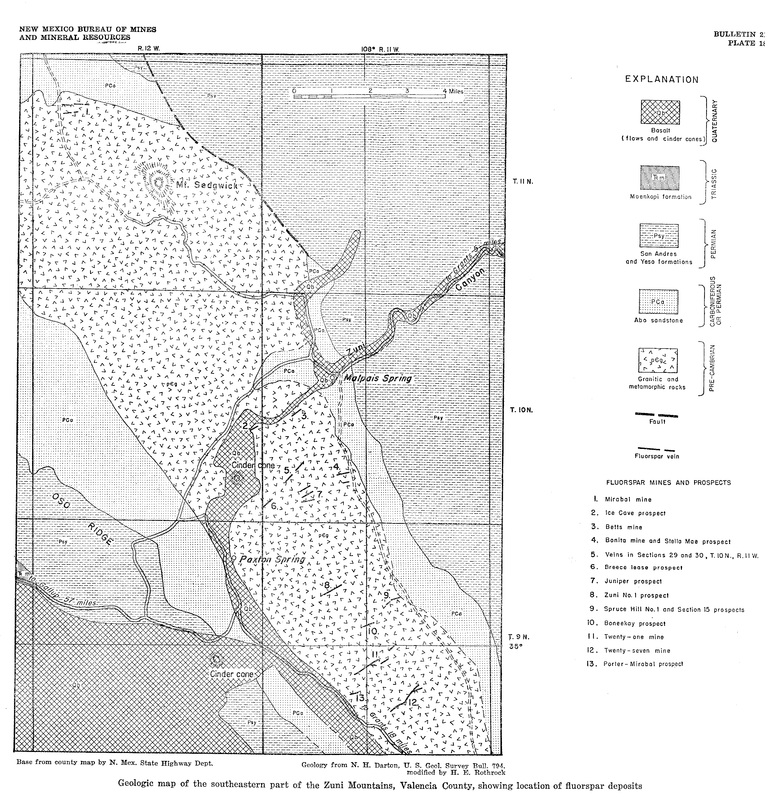

"Because the Bonita Mine was a Very Excellent Mine" -From Jones Vs. People, 118 Colo. 271, 272 (Colo. 1948) I recently had the opportunity to visit an abandoned fluorspar (or fluorite) mine in New Mexico. The Bonita Mine is located in the Zuni Mountains, about 1.5 hours west of Albuquerque. This area has been home to both extensive logging activity, as well as mining of both copper deposits and the aforementioned fluorspar. Fluorspar, or fluorite, (a mineral I've never encountered before) was used historically within two primary industries, as a flux in the production of steel and aluminum, and as a coloring agent in ceramic glazes and glass making. Fluxes acted as purifying agents when added to the smelting furnace, helping with the removal of chemical impurities from the ore body. Fluorite, along with limestone were two of the most popular fluxes used in 20th century smelting operations, and its worth while to consider these less heralded minerals when exploring the complex environmental histories of the copper and iron industries - they add depth to the study, and have left environmental footprints which are often far removed from the sources of smelting. I've only been able to find a handful of historical records regarding the Bonita Mine (granted I've only looked online for a few minutes - as this post is tangential to my dissertation) including a lawsuit from 1948 and a State of New Mexico report from 1946, which provides the ownership information below: "The mine is on Bonita No. 5 claim, which is one of a group of six claims filed by J.L. Cornelius and Alton Head. In 1942 and 1943 it was operated by the Both Mining and Milling Company, and subsequently it was acquired by J.K. Stanland." Howard E. Rothrock, C.H. Johnson, and A.D. Hahn, "Fluorspar Resources of New Mexico", New Mexico Bureau of Mines and Mineral Resources, Bulletin 21, 1946, pp. 185. Regarding the owners listed above, I was able to find that Alton Head was issued a homesteading patent in Cibola Co., New Mexico in 1936, for the purpose of "stock raising", located on a property which is now managed by the Bureau of Land Management. J.K. Stanland was active in other mines in New Mexico, operating the Tortugas Mine near Las Cruces, as well as developing the Blue Diamond mine, which processed fluorite to be sent to flotation units in Dona Ana County. See more about Stanland below. Although I've never visited a fluorspar mine before, reading the landscape was easier than I expected. Nearly all mining operations follow similar flow charts at the points of extraction. The flow chart begins underground, within drifts and adits, moving towards the surface out of a shaft or a tunnel. The image above is a collapsed adit, which is a horizontal tunnel running towards an ore body, and likely a shaft. That's Tesa for scale. She is pretty great! When extracting ores by underground methods, miners would often selectively target the highest-grade ore bodies, maximizing their profit in the quickest amount of time. However, underground mining required developing a sophisticated and expensive underground and surface infrastructure. To avoid the cost and time required to develop underground mine workings, miners would also attempted to find new ore bodies by grubbing at the surface. This trenching feature is a likely example of that type of prospecting, generally carried out by a bulldozer, dragline, or scraper bucket. "A shaft about 100 feet deep has been sunk along the vein and at the 75-foot level is connected with an adit that extends eastward 275 feet to the surface and westward 145 feet along the strike of the vein." Howard E. Rothrock, C.H. Johnson, and A.D. Hahn, "Fluorspar Resources of New Mexico", New Mexico Bureau of Mines and Mineral Resources, Bulletin 21, 1946, pp. 185. The following legal speak is from a 1948 court document regarding a lawsuit between the Bonita Mine and the Chemical Research Co., of Colorado - it's confusing but I'm including it verbatim: "That the Bonita Trust was shipping a carload per week of fluorspar ore to the smelter." and "That Bonita was making money, was in a flourishing condition, was turning out ore and would turn out about a carload and a half a week...." " because the Bonita mine was a very excellent mine and they had the finances to enlarge the works of the Chemical Research Company with money from Bonita; that Bonita had the finances so they would carry on the expansion of the work of the plastic molding, provide the Chemical Research Company with an additional building, and bring in machinery and men; that the Bonita was one of the best fluorspar mines in New Mexico; that a large part of the ore was bought already; that the Bonita mine had the money for the works; that they were shipping some ores already — shipping a car a week which brought around $2,000 each; that dividends would start very shortly after." -From Jones Vs. People, 118 Colo. 271, 272 (Colo. 1948) "There is no evidence to indicate the depth to which the ore body exposed in the adit extends, but its length probably does not greatly extend that of the stopes." Howard E. Rothrock, C.H. Johnson, and A.D. Hahn, "Fluorspar Resources of New Mexico", New Mexico Bureau of Mines and Mineral Resources, Bulletin 21, 1946, pp. 185. From the 1943 Minerals yearbook we are able to ascertain a little more about what was actually going on at the Bonita Mine, and where the ore was being shipped and concentrated: "In June 1943 J.K. Stanland acquired the Bonita mine, where he did considerable development, in the course of which some ore was taken out and milled at the plant of Both Mining and Milling Co. The mine was acquired on December 9 by the Bonita Trust, which continued development and produced a small quantity of metallurgical-grade fluorspar. "During the first half of 1943 Both Mining and Milling Co. produced a small tonnage of fluxing-grade fluorspar at the Bonita mine in Valencia County. The company did custom milling for others at its concentrating plants at Grants." -H.W. Davis, "Fluorspar and Cryolite", in Minerals Yearbook 1943, pp. 1459. "An accurate record of the ore that has been shipped from the property is not available, but a compilation of figures from various sources indicates that prior to J.K. Stanland's operation at least 800 to 900 tons of ore had been shipped." Howard E. Rothrock, C.H. Johnson, and A.D. Hahn, "Fluorspar Resources of New Mexico", New Mexico Bureau of Mines and Mineral Resources, Bulletin 21, 1946, pp. 185. I didn't see any processing equipment at the mine. I'm assuming that whatever machines were there were removed when the mine closed. There likely was a small hoisting engine, jaw crusher, grizzly, and some sort of water tank. It seems like the majority of fluorspar from the Zuni Mountains was custom milled at a jigging mill, at least during the early 1940s. If I happen to make it back to the area, I'll be sure to try and dig up some more information on the Both Mining and Milling Co.

2 Comments

John Lucero

12/29/2020 10:08:21

I liked your article as my father and some of his brothers worked and the families lived on the mining camp. My sister, Mary Salazar was born there on December 27, 1941. Our family moved from the campsite to Grants, after the mine closed. We grew up and went to school there. Mary still lives in Grants. I left in 1957 when I enlisted in the USAF.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorJohn Baeten is a Postdoctoral Fellow in Spatial Analysis of Environmental Change in the Department of Geography at Indiana University. He holds a PhD in Industrial Heritage and Archaeology from Michigan Technological University. His research aims to connect historical process to current environmental challenges, and to contextualize the environmental legacies of industrialization as meaningful cultural heritage. Archives

September 2018

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed