|

How has iron mine expansion and abandonment transformed the landscape of the Mesabi Range over the past 70+ years?

This Spyglass Map compares aerial imagery of the Mesabi Range captured in 1947 with aerial imagery from today to illustrate how the landscape looked more than 70 years ago.

What we see is a radically reworked landscape, where lakes appear and disappear, towns expand, move, and are consumed by open-pit mines, and tailings basins replace meadows and wetlands. To navigate the map, first click the hide intro on the top of the map and then use the + and - icons on the top left of the screen - this lets you zoom in or zoom out of the current map extent (you'll note you can only zoom in so far). The home button will return to this main scene, which is modern day Hibbing, MN. You can move the spyglass around by clicking and dragging, and then navigate across the landscape by clicking and dragging the base map. This section includes historic aerial imagery for the entire extent of the Mesabi Range - that's just about 100 miles to explore. To see a larger version of this map, simply click here. This one map is a portion of a larger Story Map found here, which I will embed into website in a separate post shortly.

The historic aerial imagery included in this map were accessed and downloaded from the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources Historic Air Photos collection.

These images were then stitched together using AutoStitch (a remarkably easy to use free piece of software). Once stitched together into manageable clusters (roughly 10 sheets per cluster), I georeferenced these using topographic maps and modern aerial imagery. I hope you enjoyed exploring! Did you notice anything that has changed about your particular landscape? This work was supported by a National Science Foundation (Grant #R56645, Toxic Mobilizations in Iron Mining Contamination, PI Nancy Langston). Thanks to Nancy Langston, Don Lafreniere, and Dan Trepal at MTU for help getting these files on a server.

2 Comments

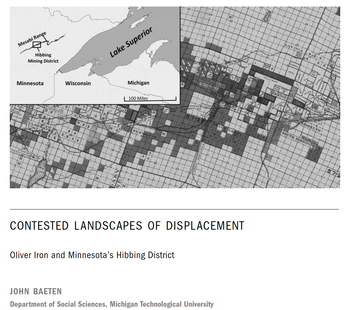

I am happy to have an article featured in the new issue of Change Over Time: An International Journal of Conservation and the Built Environment. This is a thematic issue, concerned with Landscapes of Extraction. My article, Contested Landscapes of Displacement: Oliver Iron and Minnesota's Hibbing District, explores the ways that communities, the iron industry, and the state responded to iron mining development in Minnesota's Mesabi Range. As open pit mines expanded during the 1910s, all but two communities were forced to relocate to make way for an expanding mine. Archival records reveal that communities contested mining displacements, yet this social negotiation over mining is relatively absent in current interpretative discourse. Instead, state agencies have reimagined the mining landscape, filling former mines with trout and removing much of the built environment in an effort to promote a recreational landscape atop a postindustrial one. These actions have fostered a distorted collective memory of the region's past and an industrial landscape where historical features are treated as recreational areas rather than cultural resources.

You can download the article, and peruse other interesting research from the special issue in the link above. I've been doing some digital house cleaning, which is a surprisingly really fun process. I've uncovered quite a few past projects that I've decided to publish on this website, instead of letting them languish on a junk drive.

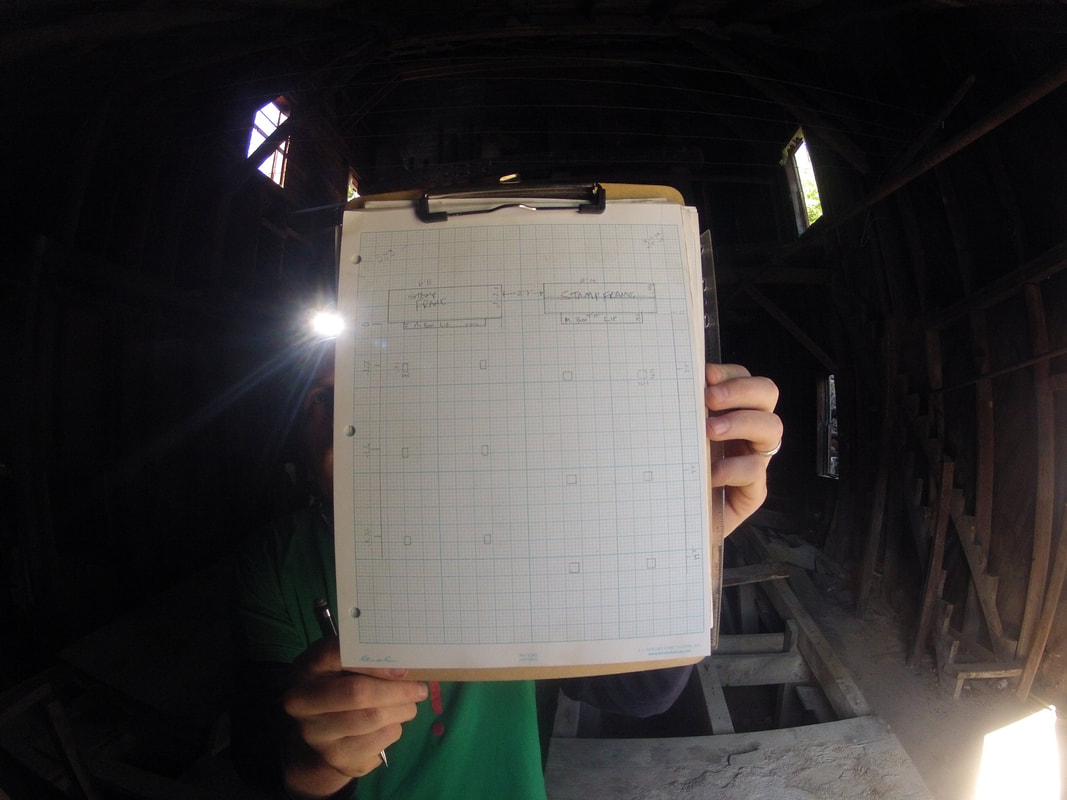

The first of these rediscovered posts focuses on a project that occurred from 2010-2012. During this time, I had the good fortune to spend the majority of my summers conducting archaeological field work in historic gold mining claims just north of Fairbanks, Alaska. This work was part of my MS in Industrial Archaeology at Michigan Tech (you can find my thesis here). Rather than just presenting a photo essay of some of the mine sites we recorded, I thought it could be educational, and maybe fun, to show some snippets of how an industrial archaeologist records a complex standing stamp mill. Specifically, I hope this post breaks down the process of documenting a multi-story industrial facility, and next, how these data can be used to reconstruct how that technological system functioned. In 1955, Carson Lake did not exist Growing up in the flatlands of Northeast Wisconsin, I have long been fascinated with big topography and consistently drawn to maps - particularly those that use raised relief to depict elevation changes.

Raised relief maps are models of reality that present landscape formations in 3-Dimensions - allowing the user to both see and feel the plains, valleys, and mountain ranges of the world. As a child, I remember being intrigued by the vast raised ridges that ran across the Americas - one flowing from Alaska to New Mexico, and another running through Ecuador, Peru and Chile - places in which I would later work, travel, and live. These raised relief maps brought the dramatic geologic formations that occupy much of the western extent of the Americas to the classrooms of the topographically challenged Midwest. Post-mining landscapes often lie. What we see on the landscape today does not necessarily reflect the complex history in which that landscape was shaped. Instead, post-mining landscapes tell a story designed to convey a specific message to the public, often designed by either heritage organizations or reclamation agencies. In most post-mining landscapes, the story told by heritage organizations is often centered on either mining technology or architecture, seen in the focus on memorializing monuments representative of industrial capital. Consequently, the story that industrial heritage managers tell about post-mining landscapes often revolves around the interpretation of only a select few buildings and machines. However, these tangible manifestations make up only a small percentage of the post-mining landscape, while the overwhelming environmental impacts from mining are generally avoided.

Artifact (n): a characteristic product of human activity "What is the coolest artifact you have ever found?" Countless archaeologists have been asked this question, and when directed at me it has always posed a challenge. Was it a green obsidian spear point found in Northern California? A stamp mill battery in Alaska? A chert awl in Arizona?

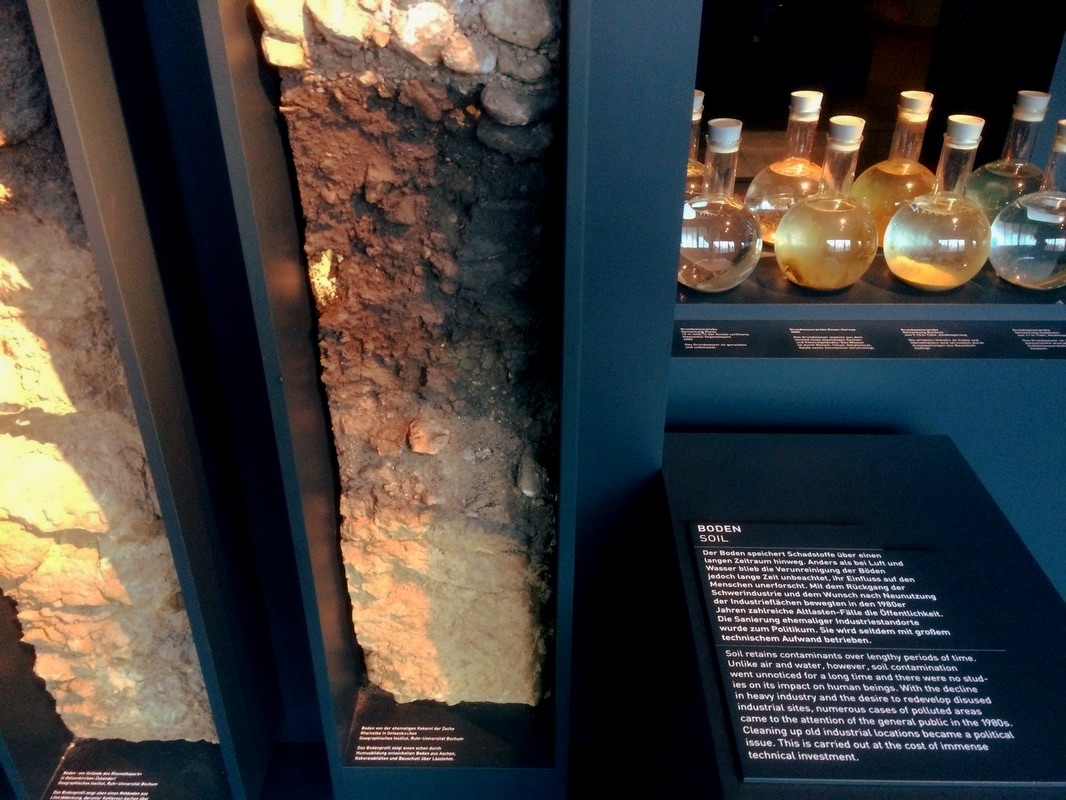

While I never have a quick answer to this question, what I do notice is that whatever my answer, the artifact is always something tangible, always something obviously human, and always rooted in technological materialism. I've been taught that an artifact is something mobile and something that was produced to serve some sort of purpose. Yet that is the orthodoxy of archaeology and heritage. What happens when we begin to challenge this convention? I was recently fortunate enough to visit some tremendous industrial heritage sites in Germany, the Landschaftspark in Duisburg, and Zeche Zollverein in Essen. At both of these sites it is easy to become overwhelmed by their sheer grandeur, one centered around an enormous blast furnace works, the other centered around a towering coal mine shaft house. While I thoroughly enjoy these megaliths of industrial prosperity, what resonated with me most was a collection of artifacts housed in the Zeche Zollverein museum exhibit - appropriately called, "Environmental Destruction and Protection". In the spring of 2012, I wrote a book review for IA: The Journal of the Society for Industrial Archaeology on the edited volume of conference proceedings: Post-Mining Landscape: Conference Documentation. The book is a collection of reflections on managing, developing, and revitalizing massive industrial landscapes after the gears of industry cease to grind. The book is filled with impressive images of reimagined industrial landscapes - a swimming pool in the middle of former colliery coking plant, a cheese cellar in an underground copper mine, and the development of a greenbelt across slag heaps in Northern France. This truly innovative work resonated with me, and this past month I had the opportunity to visit a handful of sites in the North-Rhine Westphalia region of northern Germany. This post is a collection of photographs from one of the most impressive industrial sites I've visited - The Landschaftspark Duisburg Nord located just outside of Duisburg. While this post presents an overview of the in situ remains of the former iron smelting plant and blast furnaces, a future post will examine the transformation of the site from a post-industrial ruin into a vibrant cultural attraction - successfully melding history, nature, and industry into a model example of industrial reuse.

A Geospatial Approach to Uncovering the Hidden Waste Footprint of Lake Superior's Mesabi Iron Range12/8/2016 Free Access (Until 01/26/17) to Our Recent Publication in The Extractive Industries and Society here Abstract: "For decades, the Lake Superior Iron District produced a significant majority of the world’s iron used in steel production. Chief among these was the Mesabi Range of northern Minnesota, a vast deposit of hematite and magnetic taconite ores stretching for over 100 miles in length. Iron ore mining in the Mesabi Range involved three major phases: direct shipping ores (1893–1970s), washable ores (1907–1980s), and taconite (1947–current). Each phase of iron mining used different technologies to extract and process ore. Producing all of this iron yielded a vast landscape of mine waste. This paper uses a historical GIS to illuminate the spatial extent of mining across the Lake Superior Iron District, to locate where low-grade ore processing took place, and to identify how and where waste was produced. Our analysis shows that the technological shift to low-grade ore mining placed new demands on the environment, primarily around processing plants. Direct shipping ore mines produced less mine waste than low-grade ore mines, and this waste was confined to the immediate vicinity of mines themselves. Low-grade ore processing, in contrast, created more dispersed waste landscapes as tailings mobilized from the mines themselves into waterbodies and human communities."

I recently had the opportunity to write a blog post for NiCHE, The Network in Canadian History and Environment, as part of their "Seeds: New Research in Environmental History" series. In this post I summarize the construction of an Historical Geographic Information System (HGIS) to help reveal the producers and content of historic mine waste, research described in fuller detail in a recent publication through The Extractive Industries and Society.

If you have been following this blog, you will know that part of my research has involved tracking the facilities that processed low-grade iron ores and produced tailings in the Mesabi Range. These facilities were called beneficiation plants (ben-eh-fiss-ee-ay-tion plants), iron ore concentrators, or ghost plants if you are referring to this blog. Historically, 88 beneficiation plants stretched across the Mesabi Range. Today 13 of these plants remain standing - but 2 weeks ago, I would have told you that there were 14. Time flies when you are having fun. Coming up with these figures was a convoluted process. Since processing plants are not tracked by any government agency, and because most mining heritage sites tend to focus their attention more on the mines than the processing plants, pinpointing were these facilities once existed required quite a bit of archival legwork. Identifying the locations of these 88 beneficiation plants required examining historical maps, historical aerial imagery, paging through old trade journals, and using web-based services like MNTOPO to analyze the current landscape.

|

AuthorJohn Baeten is a Postdoctoral Fellow in Spatial Analysis of Environmental Change in the Department of Geography at Indiana University. He holds a PhD in Industrial Heritage and Archaeology from Michigan Technological University. His research aims to connect historical process to current environmental challenges, and to contextualize the environmental legacies of industrialization as meaningful cultural heritage. Archives

September 2018

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed