|

Ore is an economic term Fred Quivik, 2015 I've been fortunate to work with a number of great mentors and colleagues during my time as an archaeologist for the Forest Service, and as a graduate student at Michigan Tech. A benefit of being in academia is the opportunity to listen to other researchers present their own work. A recently retired history professor from MTU, Fred Quivik, who I've worked with during my MS and PhD research, presented a paper in November of 2015 on mill tailings in Montana. During this talk Fred highlighted an important fact, one that I had overlooked as I've studied mining - simply that "Ore is an economic term".

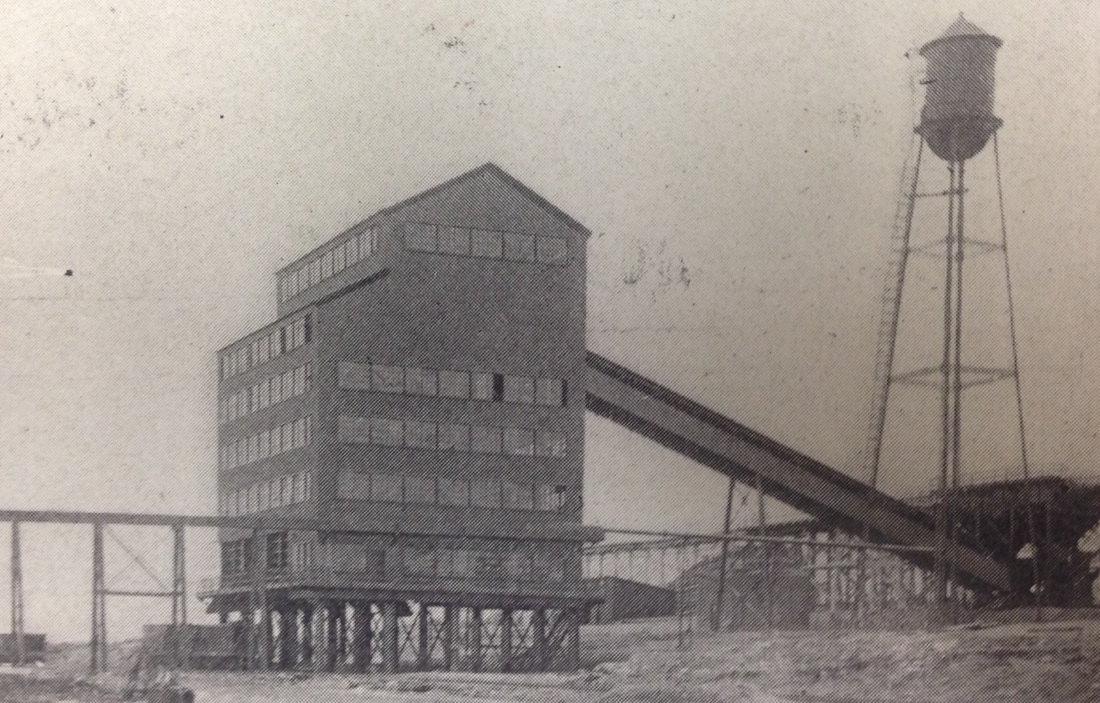

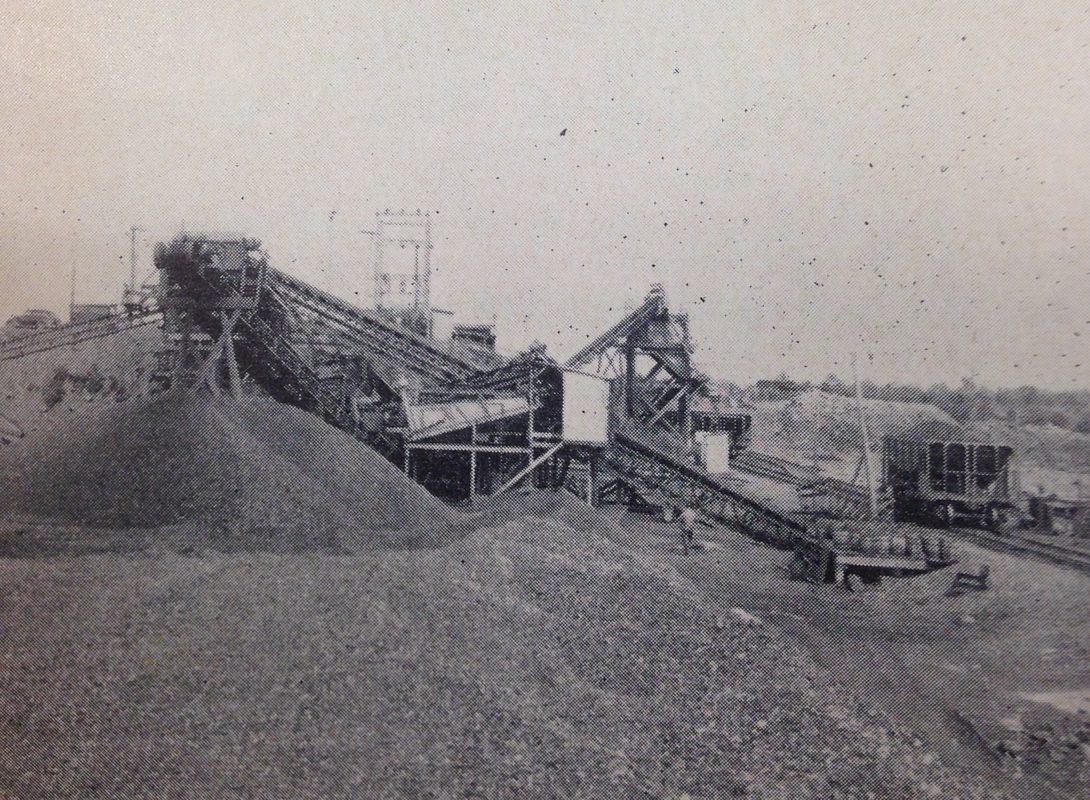

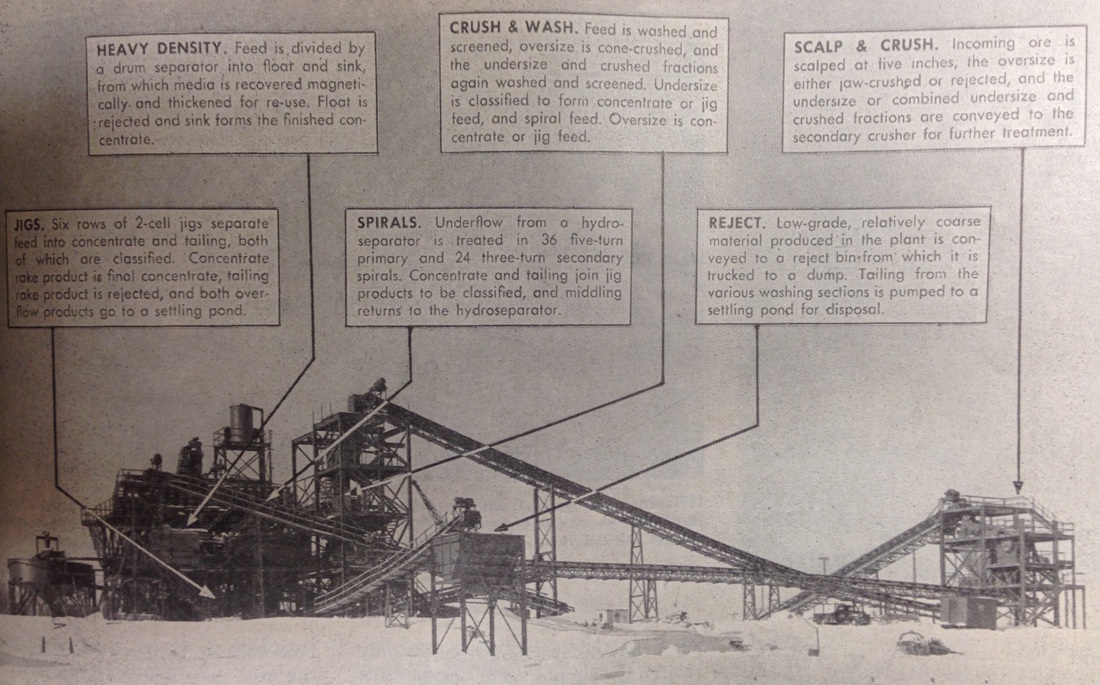

Whoa! That cogent sentence changed the way I understood the mining industry, and changed the way I looked at concepts like value and waste. In mining, what is value today, might be waste tomorrow - and vice-versa - judgments based on economics, technological development, and culture. In mining heritage we can see similar parallels, as what we value collectively can change with time, with politics, and with economics. Both of these fields, mining and mining heritage, ascribe value judgements to things, such as minerals, machines, and memory, based on shifting, and abstract cultural constructs. Since Fred's talk and as my research has progressed, I've found myself writing and reflecting about concepts like value and waste - especially how it relates to mining, heritage, and the environment - examining closely the often blurry line that we draw to divide the two. I will return to this idea later - but for now we will explore the history of the Harrison Concentrator, the third beneficiation plant constructed in the Mesabi Range, which the Butler Brothers Mining Co. used to convert a material previously considered waste into an abundant source of value in the form of iron ore concentrates.

3 Comments

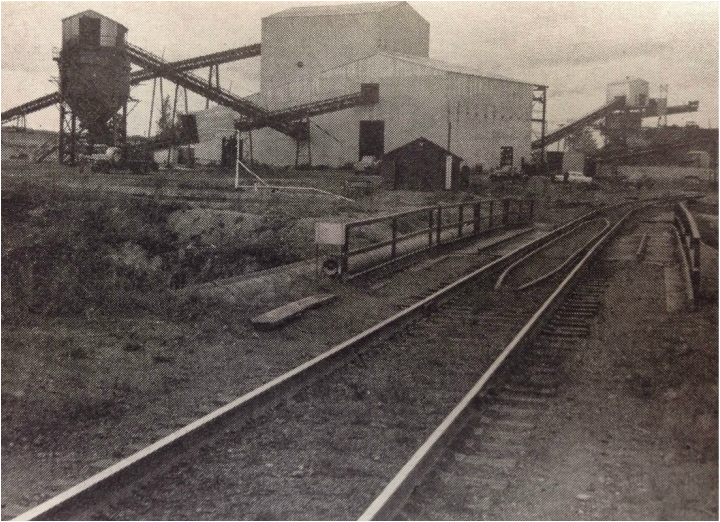

The Portsmouth Sintering Plant 1924-1966 - Fred Sutherland "Almost everything is a dull rusty red. This is the color of the railroad ties, of the soil, of the stockpiles, and even the buildings of the mines. The landscape has a blasted and forlorn look, even though most of the mines are operating, somehow (it) always seems lifeless and desolate." - George F. Brighten, 1941 I'm pleased to feature a guest post detailing a ghost plant in the Cuyuna Range of Minnesota, written by my colleague Fred Sutherland, a recent graduate from the Industrial Heritage and Archaeology Program at Michigan Tech. Fred's dissertation, "The Cuyuna Iron Range: Legacy Of A 20th-Century Industrial Community" explores the industrial history of the Cuyuna Range, through the lens of Industrial Archaeology. Enjoy JB! At a site about 100 miles south of the Mesabi Iron Range on the Cuyuna Iron Range an unusual ore refinement process was conducted during the mid-20th century. It was unusual because it was the only example of its type in the Great Lakes region and also for its scale, as the largest of its kind in the United States while it was in operation. The Portsmouth Sintering Plant operated for 42 years, even for 8 years after its local mine closed, because it processed the unmarketable portion of fine-grained iron ores found across the Cuyuna Range into a marketable product called sinter.

"The lake has a limited plant community due to poor water clarity and the shorelines have been disturbed by past mining activity." -MN DNR Upper Panasa Lake is small, murky, and unspectacular. Viewed from above, Upper Panasa Lake stands out from the dozen or so other lakes that surround Calumet, MN not because of its size or shape, but due to its pale green color - reminiscent more so of pea soup than as the aquatic home for bullhead, northern pike, and pan fish. Although its appearance may be drab, Upper Panasa's industrial past is quite vibrant, and it begins in part with the Hill-Trumbull washing plant and the 24-billion gallons of water it sucked from Upper Panasa Lake over half a century to process silica-laden low grade iron ore.

"But the hematite in the tailings seemed possessed of a wanderlust." (EMJ, Vol. 97, No. 05, Jan 31, 1914, pp. 293) Historic mining landscapes can be read as palimpsests, featuring the the ongoing conversation between an evolving technological system and its changing environment. Sometimes these conversations are easy to follow, but more often than not, they tend to resemble the creative genius of Sokal - convoluted, cacophonous, and confusing. When reading mining landscapes it is often difficult to remember that many of the mining features that may seem ubiquitous today were not always there. Instead, these features are products of an evolving technological system - artifacts of the conversation between technology and nature. In the historic Mesabi iron range, tailings ponds and tailings basins are mining features evident throughout the range's 100 mile stretch, running from Grand Rapids to Babbitt, but less than a century ago, these mining features were absent, as the concentrating plants that created them were still only nascent features on the landscape.

This brings us to a question I continue to dwell on: What impact did the sudden visibility of tailings in the Mesabi Range have on public perceptions regarding iron mining, ore processing, and the environment? Part of the answer to this question is found near Nashwauk, MN and the O'Brien Lake ecosystem, where a handful of Hibbing "publicans" saw the shoreline of their summer retreats turn red during the summer of 1912. "The North Uno washing plant, built with an eye to moving when the ore is exhausted, does a good job on the ore from the mine." -E.S. Tillinghast, Mining World, 1948. The historic mining community of Leetonia, MN is located in the eastern section of the Mesabi Iron Range, roughly 3 miles west of Hibbing, MN and 1 mile south of the massive Hull-Rust-Mahoning Pit. Shaped like an upside down "L", the community of Leetonia is laid out in an orderly grid with five streets running north-south, and five streets running east-west. The streets running north-south follow a numerical naming convention, while the names of the east-west streets bear the names of former mines, such as Morton, Dale, and Kerr - unintentional memorials to a handful of ghost mines consumed by the nation's growing demand for taconite. Both the Dale and the Kerr produced low-grade washable ore, material that was treated for a handful of years at one of the more notable mobile beneficiation plants in the Mesabi, the North Uno washing plant.

"In essence, the entire plant has the flexibility of a laboratory." (R.L. Burns, "Custom Milling Mesabi Iron Ores", in Mining World, July 1953, pp. 43) Located at the southwestern corner of the intersection of Grant Ave. and Monroe St. in Eveleth, MN, stands the world's largest free-standing hockey stick (and puck) - over 100 ft. in length and weighing in at 5 tons (the largest hockey stick is actually in Canada and is nearly twice as long as the monument in Eveleth). Dubbed by locals as the "Stick", the landmark was first dedicated by the city of Eveleth in 1995, and after seven years of harsh northern Minnesota winters the "Stick's" aspen body began to deteriorate, leading to the erection of a new "Big Stick" (measurements above) in 2002.

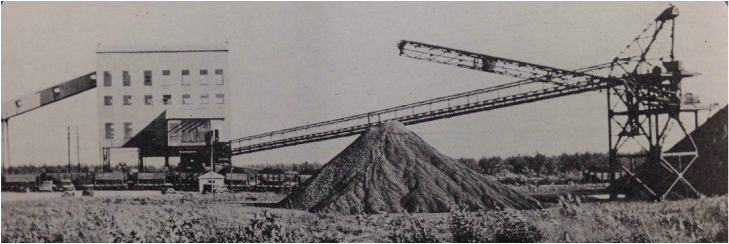

The "Big Stick" and the associated US Hockey Hall of Fame serve as tourist attractions for the community of Eveleth, designated as "The Capital of American Hockey" - but Eveleth's contemporary hockey heritage owes much to its industrial past and the large open pit mines and processing plants that fueled the city's cultural and environmental landscape for nearly a century. Located in the far eastern extent of the Mesabi Range - a region known more for its rich supply of direct shipping ore and taconite deposits than for low-grade washable ore - the community of Eveleth was also home to the Mesabi's first custom beneficiation plant - The Coons-Pacific Iron Ore Concentrator - a product of savvy engineering and corporate foresight. "Canisteo iron ore concentrate is a well-known trade name in many of the large steel plants of the East, as it is the Canisteo mine which pioneered concentration of iron ore on the Mesabi iron range on a commercial scale." Skillings' Mining Review, Vol. 29, No. 28, Nov. 2, 1940 The historic Canisteo mining district lies within the far western end of the Mesabi, running a length of nearly 10 miles beginning near Grand Rapids and moving northeast towards the town of Holman. I've covered this region in two other posts - the first on the Trout Lake Concentrator, and another on the Hunner Concentrating Plant. The Canisteo District was home to 10 beneficiation plants which operated for nearly 70 years, from 1907 to the early 1980s. All of these facilities now exist as ghosts on the landscape, visibly absent yet environmentally persistent. The former location of the Canisteo Washing Plant is submerged within the flooded cavity of the Canisteo Mine, where largemouth and smallmouth bass, northern pike, bluegill and cisco now swim over the roadbeds where 15-ton dump trucks used to busily transport ore from mine to mill.

Here's a first draft of a time series map we've created exploring natural resource use within iron ore processing plants in the Lake Superior District. This video is showing the amount of water used in these plants to process low-grade ores. Taconite, which required additional water for the pelletizing process, comes into play around 1960, resulting in dramatic increases in the scale of water use. Calculating the amount of water required was factored by averaging reported water use at these plants over time, with the more recent plants, such as the taconite ones, providing more concrete data.

Let me know if you have any suggestions! "This installation will do more than the old type of installation did, and at less cost..." -Earl Hunner, "Recent Developments in Open-pit Mining on the Mesabi Range" Keewatin, MN is located at the far eastern extent of Itasca County, at the juncture of Itasca and St. Louis Counties in Northern Minnesota. The Mesabi Range is bifurcated politically, but also geologically, as the western end of the Mesabi, those ore bodies within Itasca County, tend to be heavy in silica and light in iron, and were known historically as western Mesabi washable ore.

During the 1929-1930 mining season, the M.A. Hanna Co. began stripping the overburden encasing its new Mesabi Chief Mine, located just west of Keewatin, and drawing plans for the construction of a washing plant located south of the mine itself. This week's post revisits the town of Coleraine, MN - home of the first beneficiation plant in the western Mesabi, the Trout Lake Concentrator. Coleraine is also home to the Canisteo Pit, a long and narrow open pit mine that borders the north end of the town. Like many of the abandoned open pit mines in the western Mesabi, the historical mines that created the Canisteo Pit turned off their dewatering pumps as their ore bodies became exhausted, allowing for the Pit to transition into a lake. The Mesabi Range continues to transition, moving from an agricultural landscape into an industrial one, and now from an industrial landscape into a landscape dominated by leisure and recreation. In addition to the abundance of pan-fish, trout and bass that now call the Canisteo Pit home, the Pit contains the historic workings of roughly 20 open pit mines that ceased shipping low-grade ores in the mid-1980s.

|

AuthorJohn Baeten holds a PhD in Industrial Heritage and Archaeology from Michigan Technological University. His research aims to contextualize the environmental legacies of industrialization as meaningful cultural heritage. Archives

May 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed